Planning Naked | July 2016

Planning Naked | July 2016

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Your (hopefully) hilarious guide to everything about the latest issue of APA’s Planning Magazine

Note: In all likelihood, one of the better issues of Planning Magazine in the last 15 years from the point of view of objective reporting and displays of good old-fashioned, common sense… or, at least, the first half of the issue. Things start to spectacularly fall apart beginning on page 27.

In the words of Marvin Gaye, what’s going on? Is there a new editor at Planning Magazine? Has Planning Magazine adopted new editorial guidelines? There’s little objectionable content about the first 12 pages of the July 2016 issue (From the Desk of APA’s Executive Director and News sections). It’s almost reading bliss.

I come not to bury Planning Magazine but to (in part) praise it. “It’s Time to Rethink Temporary Use” by David S. Silverman in the Legal Lessons section (pp. 13) is praiseworthy. “Traditional zoning is often a clumsy tool to address the regulatory land-use issues raised by” alternative, often temporary uses. If this sanity continues, I may have to retire the “Planning Naked” column on The Outlaw Urbanist.

Leave it to Rio. “Rio Gets Ready by Michael Kavalar (pp. 14-18) reports on Brazil’s preparations for the 2016 Olympics next month and pacification; “an official government policy of structured military occupation of informal communities with the intent of fully incorporating them into the formal city.” This is a well-written, informative piece that balances the positives of legacy projects associated due to the Olympics with local tensions arising from a pacification policy that predates these legacy projects.  The article successfully touches on these topics, giving them some context, without losing sight of their complexities (for good and ill) in terms of politics and planning.

The article successfully touches on these topics, giving them some context, without losing sight of their complexities (for good and ill) in terms of politics and planning.

Taking the long view. “Winning at Their Own Games” by Kristen Pope (pp. 19) takes a brief look at adaptive reuse of facilities in Lake Placid, New York and Park City, Utah after the Olympics left town. “London’s Olympic Legacy” by Ben Plowden (pp. 20-21) follows the same story in a little more detail after the London Olympics with particular focus on London Transport. Both are interesting, informative pieces lacking the soapbox of Planning Magazine’s usually hidden agenda in the past. Again, what’s going on?

To Shop or Not to Shop, that is the Question. “From Bricks to Clicks” by Daniel G. Haake, Jeffrey M. Wojtowicz, and Johanna Amaya” (pp. 22-24) provides the ‘meat’ of this issue about the effects of e-commerce on neighborhoods, which was touched on by James Drinan in the From the Desk of APA’s Executive Director section. The piece is a thoughtful consideration of the issues surrounding increased freight deliveries of e-commerce without resorting to the standard ‘default’ answer of larger road widths and bigger floor plates in the post-war period. The creeping evidence of planning sanity is a blessed relief to this long-time victim. This article is well worth the read for planners.

It’s the business model, business model, business model. “Big Box Bust?” by Andrew Starr covers Wal-Mart’s announced closure of 154 locations nationwide, 102 of which are Wal-Mart Express stores experimenting with smaller floor plates and pared down merchandising serving a smaller (usually poorer) customer base. Starr correctly points out that ‘mindless’ application of Wal-Mart’s long-term business model for its big box stores (‘but that’s the way we’ve always done it’) on the site selection process was a likely culprit for the retailing giant incorrectly siting its Express stores; not that a ‘big box’ floor plate is necessary to survive and thrive in retail in today’s world. He points to the success of the Dollar General and Dollar Tree brands in fighting off competition from Wal-Mart Express stores as a counter example. Again, another good article; concise, objective, and spot-on.

Sigh, and there it is… mo’ money, mo’ money, mo’ money. The highlight box for “The Road to Quito” by Greg Scruggs (pp. 27-33) states “Habitat III is a ‘clarion call for planning’ that planners will pay more dividends for the profession” (our emphasis), which sounds so self-serving as to be repulsive. I don’t even want to read this article but, for anyone who might enjoy reading Planning Naked, I will. “In 1976, a bunch of Hippies…” Oh. My. God. Not a good start. Now the name-dropping, legitimacy by association. Sheesh. Now a list of pleasant sounding, meaningless bullet points using ‘synergy words.’ I can’t… go… on. This article has everything that is wrong with planning masturb… excuse me, the planning profession. The July 2016 issue of Planning Magazine was going so well until this stink bomb was dropped into the middle of the issue. Guess I don’t have to worry about retiring this column yet.

Hard core issues through a soft core lens. “One Size Does Not Fit All” by Katy Tomasulo (pp. 32-36) does have some interesting information about the housing recovery and statistical trends in the housing market. However, the author is too lackadaisical about filtering through the developer/homebuilder ‘post-war’ paradigm (e.g. suburbanization) to get at the real core of the issue. For example, NHB states they know Millennials want to become homeowners eventually (true) but that does not necessarily translate into big suburban homes (implied but false). The ‘smaller’ lot sizes discussed are still too big and don’t capitalize on the small house movement to increase affordability, etc. There’s some informative stuff in this article but the reader needs deploy critical thought to really dig for the takeaways. Good intentions but soft focus… and we all know the preferred pavement material for the road to hell.

With apologies. “Whatever Happened to HAMP and HARP?” by Jake Blumgart (pp. 36-37) is informative about the failure of the Federal programs, HAMP and HARP, established in the aftermath of the 2008 Financial Crisis to assist homeowners, but blatant in excusing the Obama Administration, Democratic Congress, and the banks for the failure of these programs by laying the blame at the feet of those very same homeowners (“If a financial institution was promising you something too good to be true, most families—after having been through what they had been through—said, ‘I’m not touching this…”). Right about the symptoms, wrong about the cause, so the conclusions are counter-productive.

More softer core. “Ever Green: Connecting to Nature in a Digital Age” by Tim Beatley (pp. 38-39) is interesting but harmless news fluff. Of course, most extinctions these days are due to the unprecedented growth of the world’s population in the post-war period. Extraterrestrial colonization and/or a massive, human depopulation event are the only substantive answers to the problem. It’s very scary that the second seems far more likely than the first.

In defense of fast food. I’m not sure about the purpose of Bobby Boone’s Viewpoint article “Fast Food’s Bad Rap” (pp. 44). Is ‘persecution of fast food’ even a thing? Sounds like a ‘first-world’ problem.

Planning Naked is an article with observations and comments about a recent issue of Planning: The Magazine of the American Planning Association.

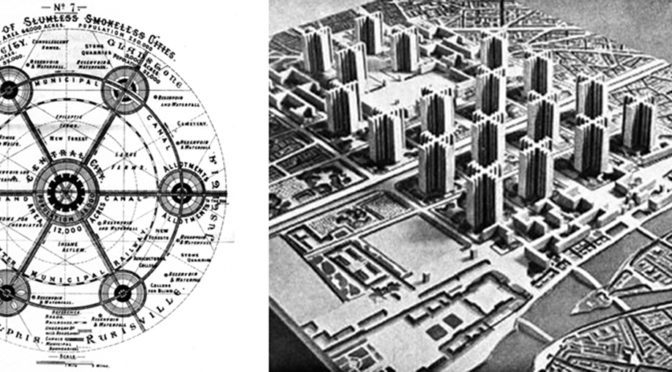

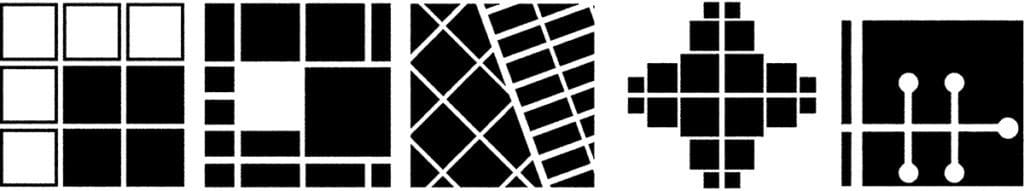

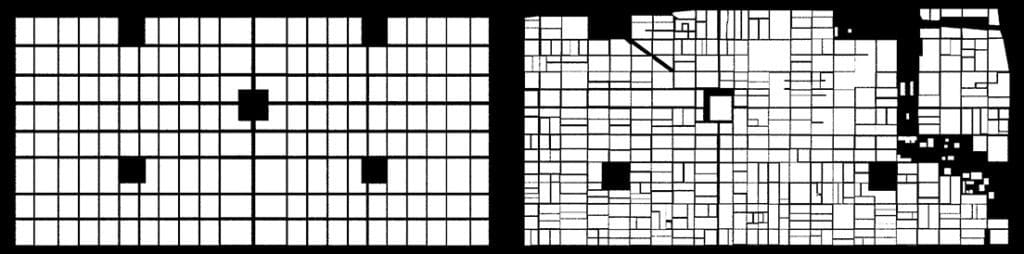

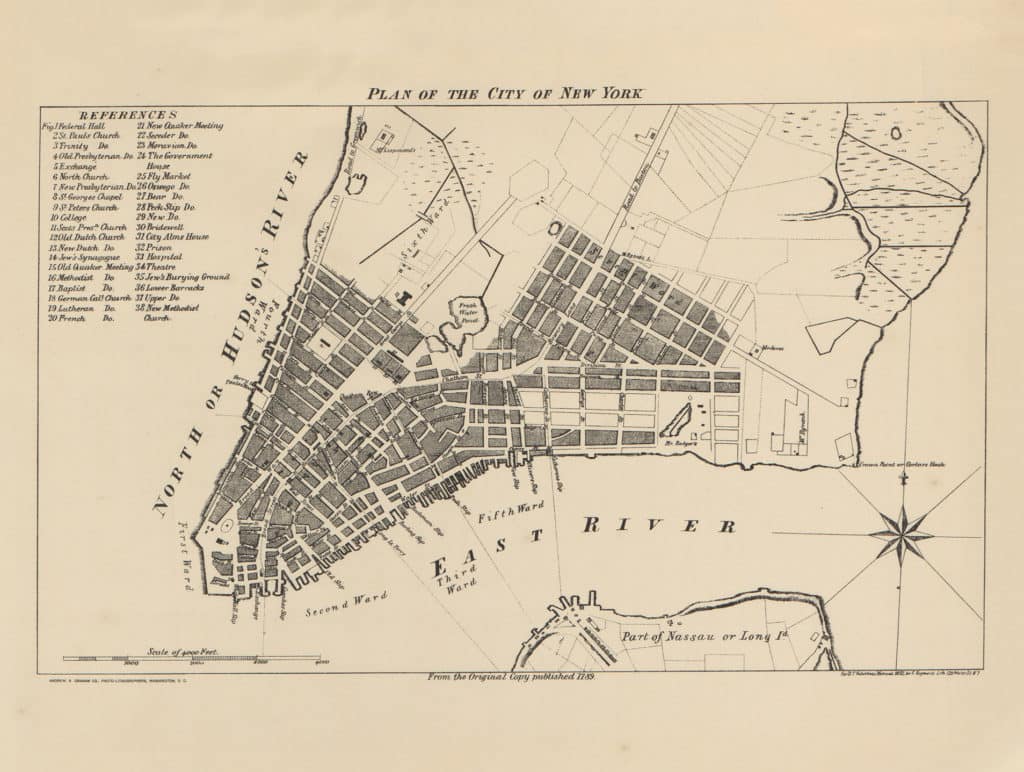

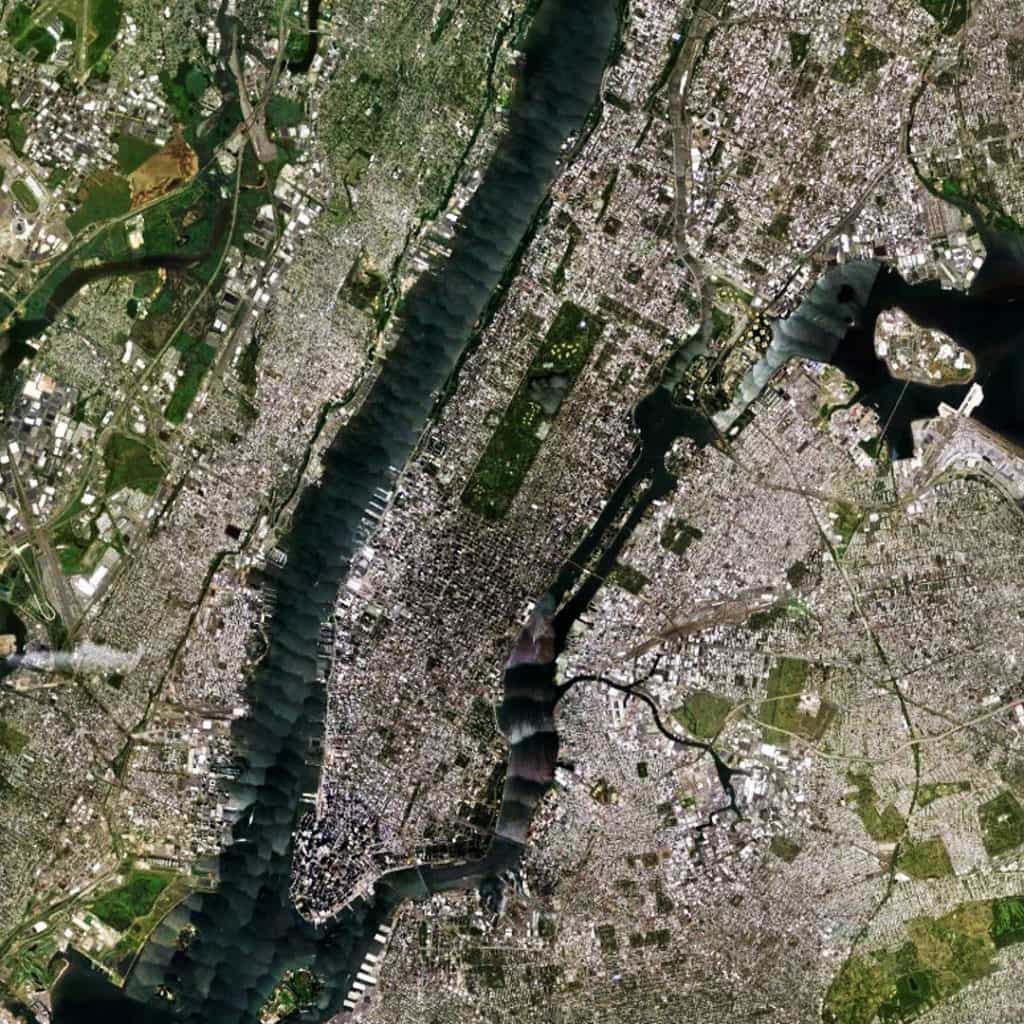

The key is the incidence or deficiency of a readily apparent geometry in the physical composition of streets and blocks in plan. American cities tend to possess such geometries so they are regular grids. European or Middle Eastern ‘organic’ cities appear to lack such geometries so they are deformed grids. Others have defined this as the difference between composition and configuration to better distinguish between how we view the city (static form) and how it works (dynamic process). Composition is an easy-to-grasp, understand-all-at-once description and configuration is a more complex view of relations amongst elements that potentially affect urban functions. This distinction is often confused or misunderstood, inevitably leading us to a theoretical dead-end.

The key is the incidence or deficiency of a readily apparent geometry in the physical composition of streets and blocks in plan. American cities tend to possess such geometries so they are regular grids. European or Middle Eastern ‘organic’ cities appear to lack such geometries so they are deformed grids. Others have defined this as the difference between composition and configuration to better distinguish between how we view the city (static form) and how it works (dynamic process). Composition is an easy-to-grasp, understand-all-at-once description and configuration is a more complex view of relations amongst elements that potentially affect urban functions. This distinction is often confused or misunderstood, inevitably leading us to a theoretical dead-end.

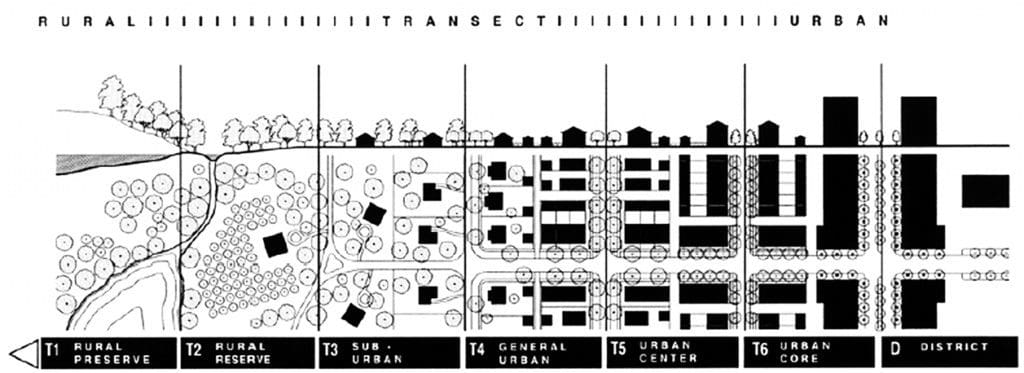

If we focus on the static and dynamic relationship between form and process, composition and configuration, in the design of the urban grid, a basic set of design decisions having formal and process implications for urban space can be identified.

If we focus on the static and dynamic relationship between form and process, composition and configuration, in the design of the urban grid, a basic set of design decisions having formal and process implications for urban space can be identified.

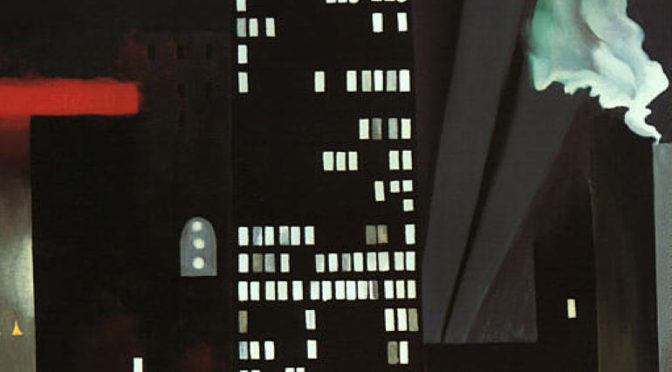

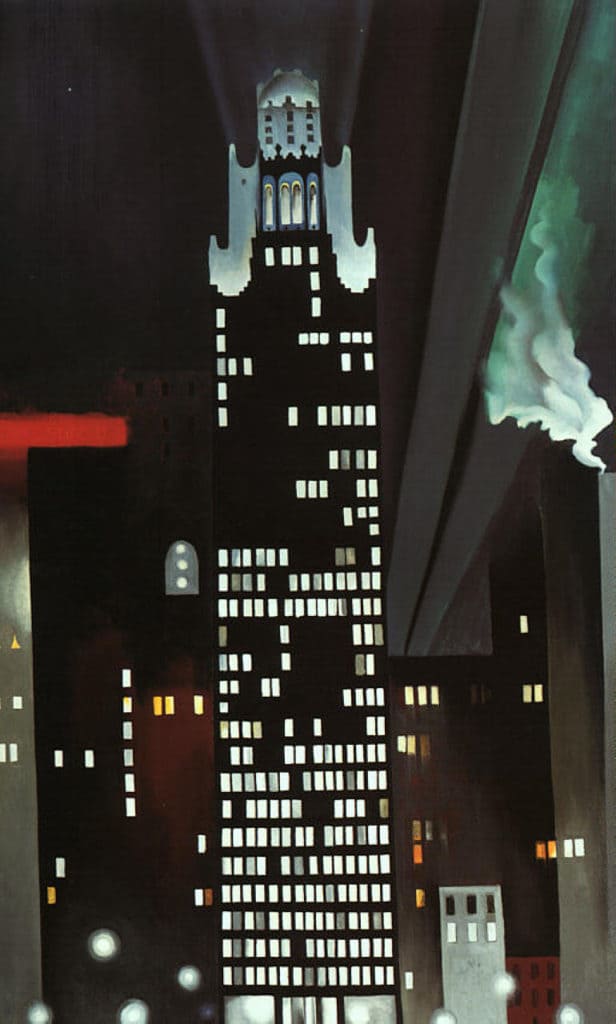

We can say this with some confidence because if you were to remove all of the ‘painted light’ from this painting, only a black canvas would remain. It is this ‘painted light’ that provides a subtle richness and contextual depth to the best of O’Keeffe’s cityscape paintings. Later, we will see more explicit examples in her other paintings, for example in The Shelton with Sunspots (1926). In this sense, the subject is the artifice of form emerging from the arrangement of light. The fact the words ‘Radiator Building’ and ‘New York’ are in the title of the painting is completely inconsequential and accidental to the subject of the piece. It is also misleading on O’Keeffe’s part by naming the painting in this manner. However, this is completely consistent with her tendency to be opaque when it comes to the subject matter of her own paintings. As architects and planners, O’Keeffe’s painting shows us how we can expand our perception of the city beyond the conventional (form) to see its richness in other, more subtle – and, perhaps, richer – ways (light).

We can say this with some confidence because if you were to remove all of the ‘painted light’ from this painting, only a black canvas would remain. It is this ‘painted light’ that provides a subtle richness and contextual depth to the best of O’Keeffe’s cityscape paintings. Later, we will see more explicit examples in her other paintings, for example in The Shelton with Sunspots (1926). In this sense, the subject is the artifice of form emerging from the arrangement of light. The fact the words ‘Radiator Building’ and ‘New York’ are in the title of the painting is completely inconsequential and accidental to the subject of the piece. It is also misleading on O’Keeffe’s part by naming the painting in this manner. However, this is completely consistent with her tendency to be opaque when it comes to the subject matter of her own paintings. As architects and planners, O’Keeffe’s painting shows us how we can expand our perception of the city beyond the conventional (form) to see its richness in other, more subtle – and, perhaps, richer – ways (light).