Las Vegas: The Transcendental City

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.outlaw-urbanist.com

Twitter: @OutlawUrbanist

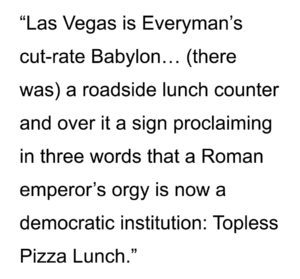

Las Vegas is a source of fascination. It has been since the publication of Learning from Las Vegas in 1972. Some say Las Vegas is “the way you’d imagine heaven must look at night.” Norman Mailer describes the city thus; “the night before I left Las Vegas I walked out in the desert to look at the moon. There was a jeweled city on the horizon, spires rising in the night, but the jewels were diadems of electric and the spires were the neon of signs ten stories high.” Alistair Cooke observes, “Las Vegas is Everyman’s cut-rate Babylon… (there was) a roadside lunch counter and over it a sign proclaiming in three words that a Roman emperor’s orgy is now a democratic institution: Topless Pizza Lunch.”  Cooke implies waitresses were serving pizza sans clothing but it could have meant the roadside lunch counter was serving its pizza lunch sans toppings, i.e. Margherita. Given Las Vegas’ reputation, it is probably wise to assume both options were on the menu. In any case, architects and urban planners have shared this fascination with the ‘Modern Babylon’ of Western civilization.

Cooke implies waitresses were serving pizza sans clothing but it could have meant the roadside lunch counter was serving its pizza lunch sans toppings, i.e. Margherita. Given Las Vegas’ reputation, it is probably wise to assume both options were on the menu. In any case, architects and urban planners have shared this fascination with the ‘Modern Babylon’ of Western civilization.

Learning from Las Vegas narrowed its arguments against the precepts of Modernism in favor of a new theoretical approach. The emergence of Post-Modernism as a distinctive architectural style overshadowed some of the most remarkable things in that book. This unsurprising since the point of examining the “phenomenon of architectural communication” where the “symbol in space (comes)

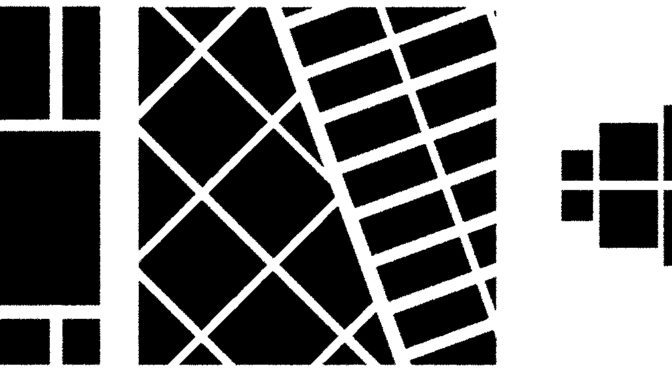

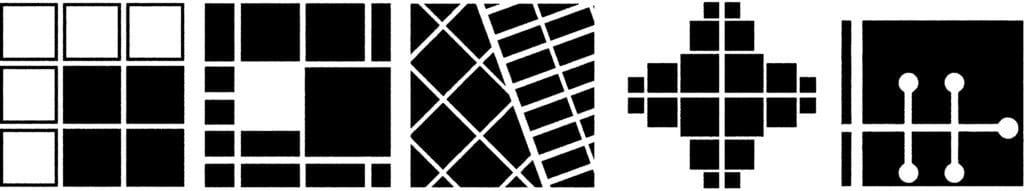

before form in space” in Las Vegas and, specifically the famous Strip, was to expand to the urban level a theory Robert Venturi had already outlined in 1966’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. The preoccupation with the semantics of architectural form in Post-Modernism – and its successor, Deconstructivism – took to heart what Learning from Las Vegas showed us to the exclusion of what was said. For example, there is an implicit acknowledgement of a spatial dimension to the pattern of urban functions in Las Vegas. Namely, “a set of intertwined activities that form a pattern on the land… the Las Vegas Strip is not a chaotic sprawl but a set of activities whose pattern, as with other cities, depends on the technology of movement and communication and the economic value of land.” The book also extensively uses plan representations such as figure-grounds to reveal crucial information about the functional structure of urban space in Las Vegas during the late 1960s.

This is a little remarked upon yet still remarkable concession, i.e. more than semantics is going on in Las Vegas. Albert Pope seizes on this concession in Ladders (1996) to argue the “urbanism of the Strip was itself structured on a relentless linear armature… in contrast to the original Las Vegas gridiron and the pedestrian ‘strip’ of Fremont Street, the organization of the upper strip was a discrete and reductive axis of development – a complete linear city.”

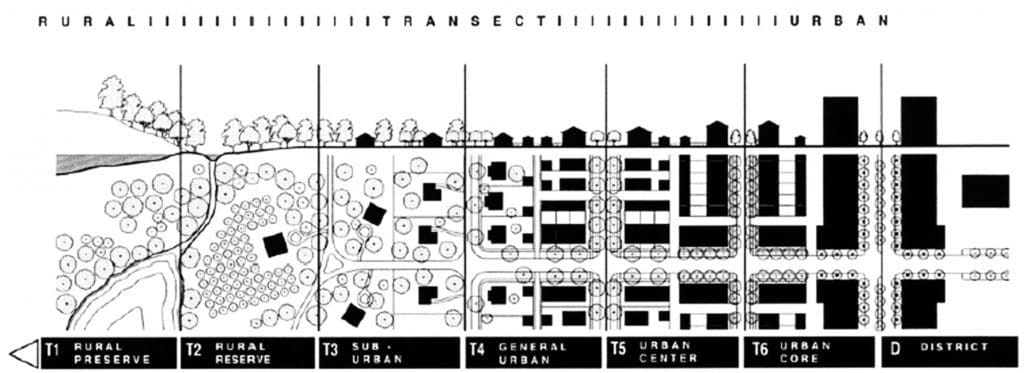

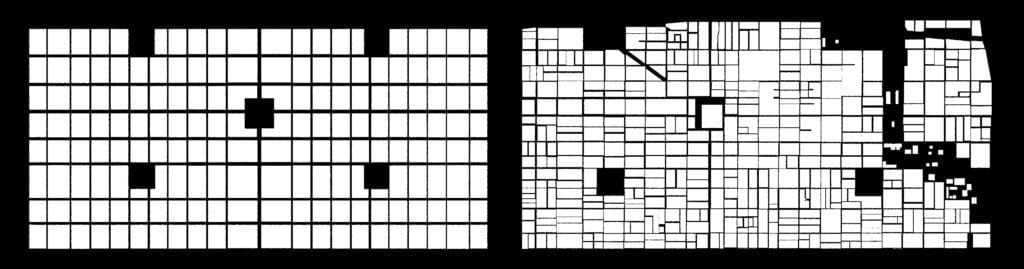

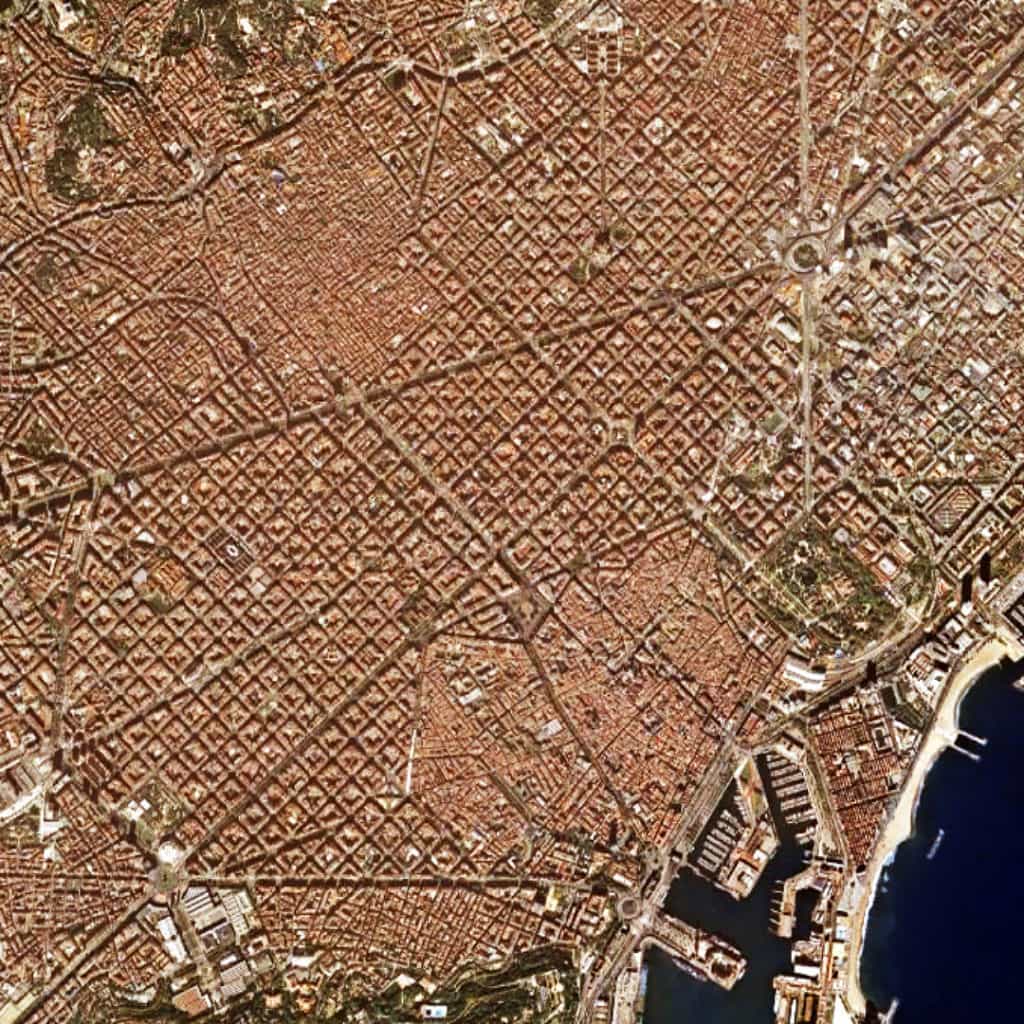

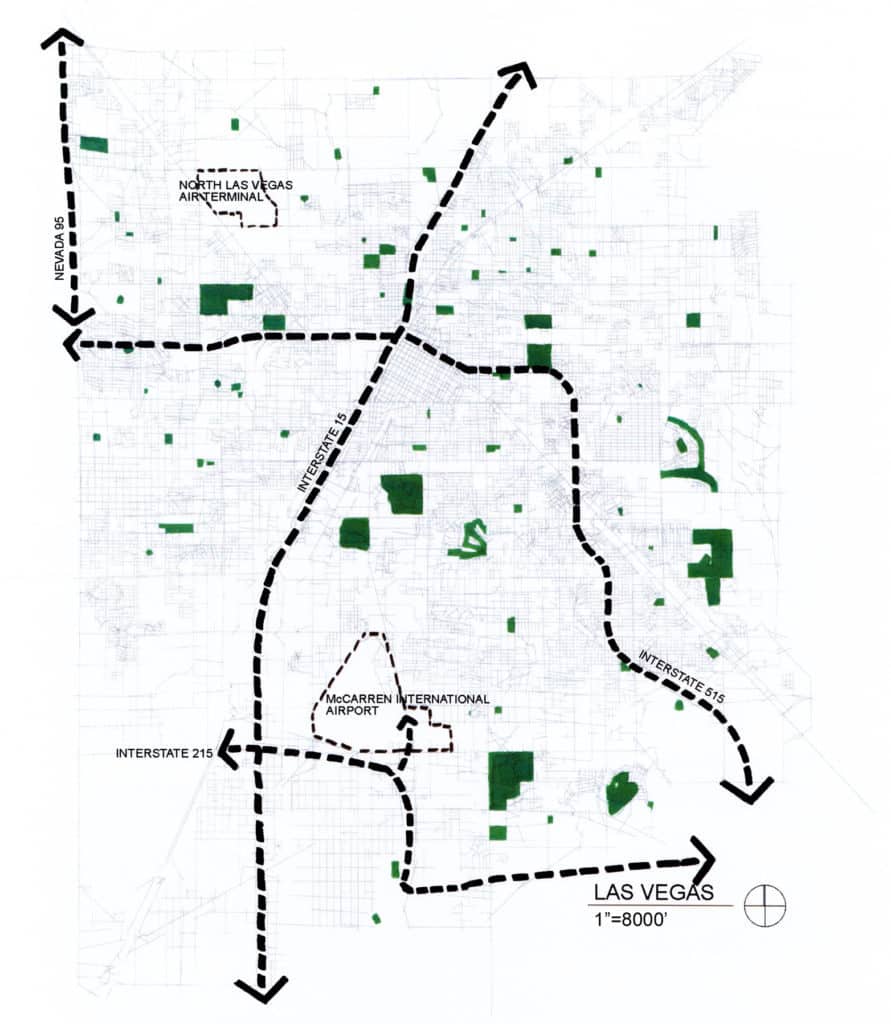

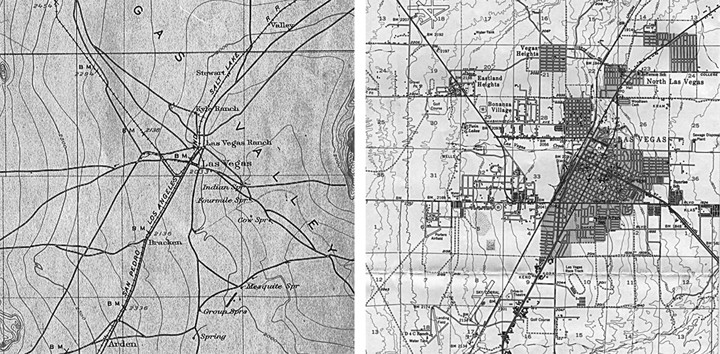

In hindsight, the flaw of Learning from Las Vegas is taking an urban object as a subject before its time. Las Vegas is more fascinating today than five decades ago because it represents a quintessential example of American development during the post-war period. We say this because the city is spatially transcendental. This means first, the city is characterized by congruent spatial networks occupying (grossly) the same point in space/time and second, these spatial networks exist a priori and emerge as a consequence to urban growth. By congruent, we mean coinciding at all points in terms of location since one is super-imposed over the other.  The a priori conditions are a consequence of the pattern of land division imposed by the 1785 Land Ordinance. Using computer modeling such as the configurational software of space syntax, we can ‘peel’ these congruent spatial systems apart and examine their role in Las Vegas; much like peeling layers off an onion and examining the individual layers (we know together they form an onion). The results are fascinating. First, Las Vegas has a well-defined, center-to-edge spatial pattern, the focus of which is not the Las Vegas Strip (though it is partially in the core) but the historic area/Central Business District (CBD). Second, a congruent, large-scale orthogonal spatial pattern emerging from the pattern of land division over time characterizes Las Vegas. This orthogonal grid pattern did not exist in the early 20th century (though we can infer its outline from section lines) and only began to emerge during the 1950s and 1960s before fully manifesting in the late 20th century.

The a priori conditions are a consequence of the pattern of land division imposed by the 1785 Land Ordinance. Using computer modeling such as the configurational software of space syntax, we can ‘peel’ these congruent spatial systems apart and examine their role in Las Vegas; much like peeling layers off an onion and examining the individual layers (we know together they form an onion). The results are fascinating. First, Las Vegas has a well-defined, center-to-edge spatial pattern, the focus of which is not the Las Vegas Strip (though it is partially in the core) but the historic area/Central Business District (CBD). Second, a congruent, large-scale orthogonal spatial pattern emerging from the pattern of land division over time characterizes Las Vegas. This orthogonal grid pattern did not exist in the early 20th century (though we can infer its outline from section lines) and only began to emerge during the 1950s and 1960s before fully manifesting in the late 20th century.

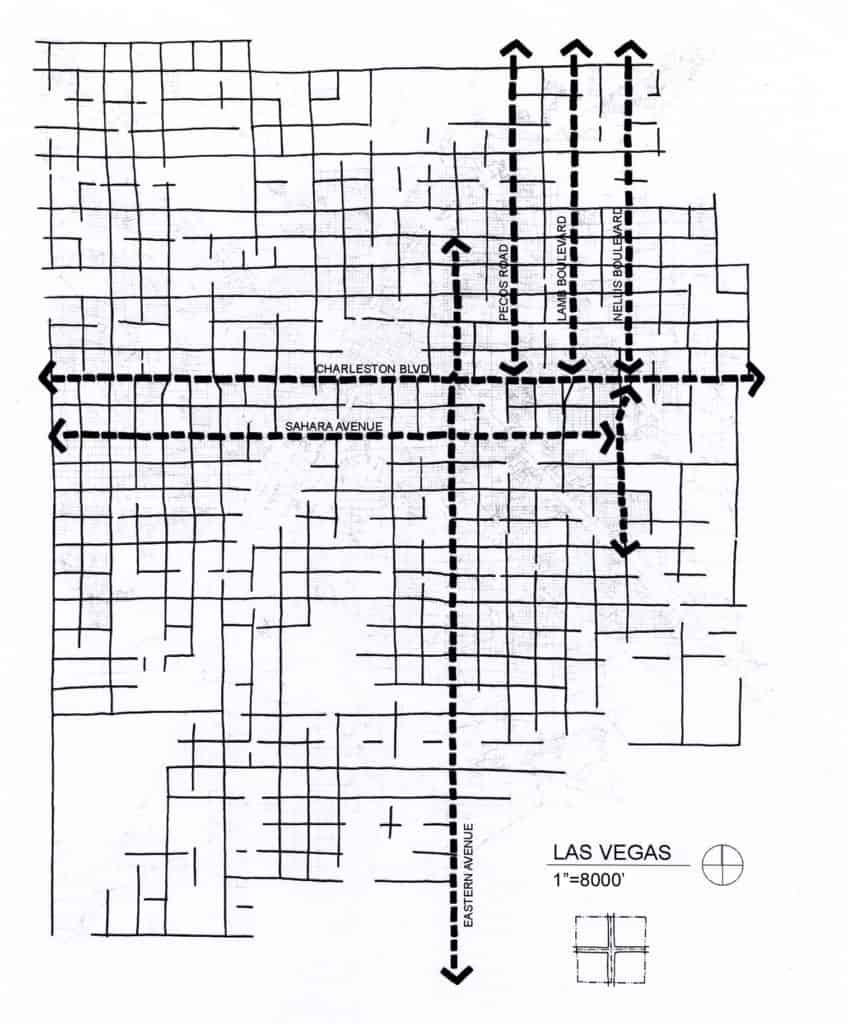

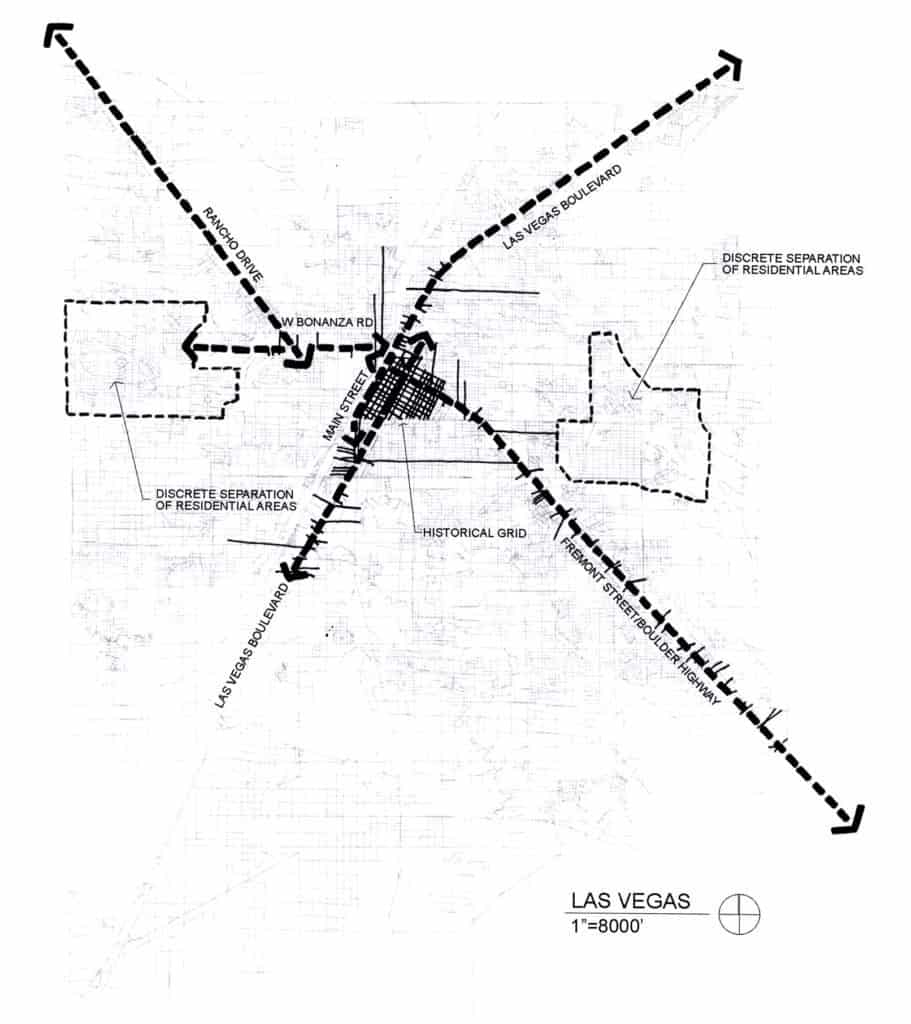

Urban form in Las Vegas has evolved over time to privilege the CBD/historic area so there is a micro-scale urban fabric that includes the historical diagonal routes from the CBD to the edges of the city in addition to this macro-scale orthogonal grid logic arising from the national grid system. We can demonstrate this by identifying all orthogonal routes aligned to cardinal directions arising from the pattern of land division. Some of these streets are long and highly connected (such as Charleston Boulevard). Others are not but all are evenly spaced apart in terms of metric distance arising from a historical process (subdivide the section, township, etc.) previously described by John Reps in The Making of Urban American/Cities of the American West. These streets represent the “strong prescriptive order” (using Pope’s terminology) of the national grid system as realized on the ground over time in the urban object. A portion of the ‘holistic’ Las Vegas super grid is composed of these large-scale orthogonal streets. This includes highly integrated routes such as Charleston Boulevard (east-west) and the southern segment of Las Vegas Boulevard (north-south).

However, this orthogonal logic is imperfectly realized. There are two reasons. First, the national grid system is a conceptual division of the land. The process Reps describes of section lines becoming main roads and so forth did not always occur for every tract of land. Second, the national grid system lays over the circumstance of the Earth. Bill Bryson succinctly summarizes the problem this causes for surveyors. “One problem with such a set-up is that a spherical planet does not lend itself to square corners. As you move near the poles, the closer the lines of longitude grow… (so) to get around this problem, longitudinal lines were adjusted every twenty-four miles… (which) explains why north-south streets… so often taken a mysterious jag” (136). This appears to be evident in diversions along the length of some north-south streets in Las Vegas. Peeling off this large-scale orthogonal street network reveals the underlying variation in the Las Vegas urban layout including a striking center-to-edge pattern formed by the historical diagonal routes and micro-scale street network. This shows how movement might utilize the urban grid, independently of the large-scale orthogonal streets.

The effect of the micro-scale street network is to privilege Las Vegas’ CBD/historical area. Configurational analysis using space syntax demonstrates this micro-scale street network is more closely related (significantly so) to the Las Vegas urban grid as a whole than the macro-scale network. This should be unsurprising. The crucial relationship for movement/urban functions in a city is center-to-edge. Edge-to-edge movement (for example, passing through Las Vegas in going from one city to another, i.e. Denver to Los Angeles) is nominally the function of the interstate highways. Instead, the macro-scale network operates as super-integrators since these streets are about six times more connected into the network compared to the average in Las Vegas.

The macro-scale network is reminiscent of a hierarchy imposed on the urban fabric by large-scale historic interventions: for example, Haussmann’s 19th century boulevards in Paris. However, there are key differences. First, the national grid system is an a priori conceptual order. Development allows this hierarchy to emerge during the growth of American cities. It is not a later remedial correction to the urban fabric. Second, it is distinct from the Las Vegas super grid. Some streets compose both but the most important are the diagonals of Las Vegas Boulevard, Main Street, Fremont Street, and Rancho Drive. If we removed the super grid in a similar experiment, then the urban fabric would disintegrate into discrete elements in the absence of these diagonals. Finally, there are highly segregated interstitial areas of the urban grid. These are suburban-type developments poorly connected into the urban grid except via the large-scale orthogonal streets defining their perimeters. We can describe this as discrete separation by linear segregation. Often, the only connection from neighborhood-to-neighborhood is via parallel curb  cuts into separate developments (with at least one development somewhere having a minimum of two entry roads). This has nothing to do with inter-connectivity and everything to do with traffic management of vehicular turning actions.

cuts into separate developments (with at least one development somewhere having a minimum of two entry roads). This has nothing to do with inter-connectivity and everything to do with traffic management of vehicular turning actions.

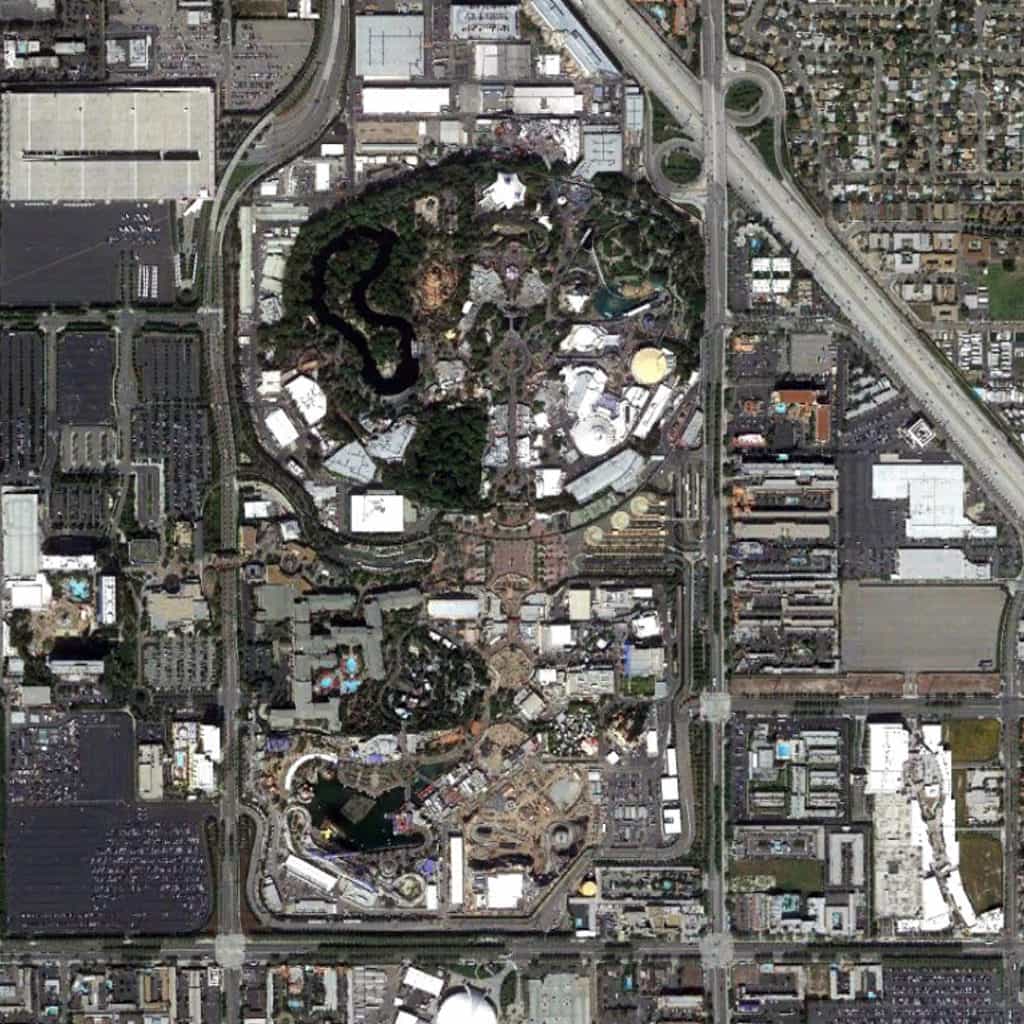

This emergent hierarchy in Las Vegas and other cities characterized by post-war growth in the 20th century (such as Phoenix and Orlando) derives from modern transportation planning. Regulatory requirements mandate the design of roads including street width, stopping distance, frequency of curb cuts, turning radius, and so on based on traffic speeds/volumes projected to utilize the streets using origin and destination gravity models Local governments have adopted these standards into their development review regulations, having a profound impact on American urban form since the mid-twentieth century. Planning to ‘minimum requirements’ gives rise to a spatial hierarchy that becomes embedded in the urban pattern. Borrowing from Christopher Alexander, Las Vegas proves that, in part, a city can be a tree. It is a different question whether it makes good urban form.

Based on excerpts from forthcoming The Syntax of City Space: American Urban Grids by Mark David Major.