“Good theory leads to good planning. Normative theory – without quantitative observation and validation using scientific method – is nothing more than subjective opinion masquerading as theoretical conjecture.”

Viewpoint | Theory Makes Perfect

By Mark David Major, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Regularly brandishing the bogeyman of Modernism, the architects of CIAM, and their industrial age vernacular to deride scientific method and endorse normative theory is a late-20th century practice du jour of the planning profession and education. It is a lot like suggesting a rape victim needs to marry her attacker to get over the experience. A shocking metaphor? Perhaps, but it is not a casual choice.

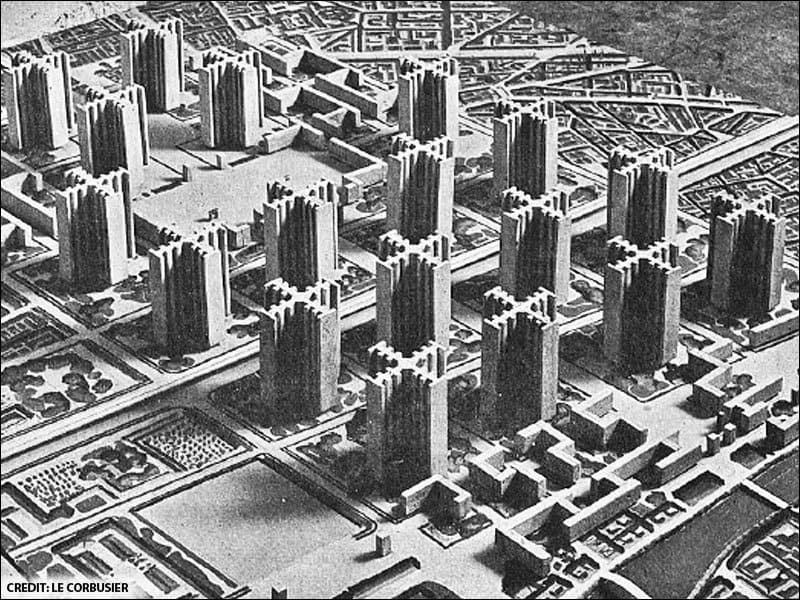

Early 20th century Modernist planning was a normative theory that aspired to science in its assertions. However, Modernism fails even the most basic tenets of being science.  It was long on observation and way short on testing theoretical conjectures arising from those observations. Without scientific method to test its conjectures, Modernism in its infancy never made the crucial leap from normative to analytical theory. Instead, the subjective opinions of the CIAM architects and planners were embraced – sometimes blindly – by several generations of professionals in architecture and planning, and put into practice in hundreds of towns and cities. Today, for the most part, Modernism has finally been tested to destruction by our real world experience of its detrimental effects, though we continue to suffer from its remnants in the institutionalized dogma of planning education and the profession. Nonetheless, it has – at long last – made the transformation from normative to analytical theory and validated as a near-complete failure; at least in terms of town planning.

It was long on observation and way short on testing theoretical conjectures arising from those observations. Without scientific method to test its conjectures, Modernism in its infancy never made the crucial leap from normative to analytical theory. Instead, the subjective opinions of the CIAM architects and planners were embraced – sometimes blindly – by several generations of professionals in architecture and planning, and put into practice in hundreds of towns and cities. Today, for the most part, Modernism has finally been tested to destruction by our real world experience of its detrimental effects, though we continue to suffer from its remnants in the institutionalized dogma of planning education and the profession. Nonetheless, it has – at long last – made the transformation from normative to analytical theory and validated as a near-complete failure; at least in terms of town planning.

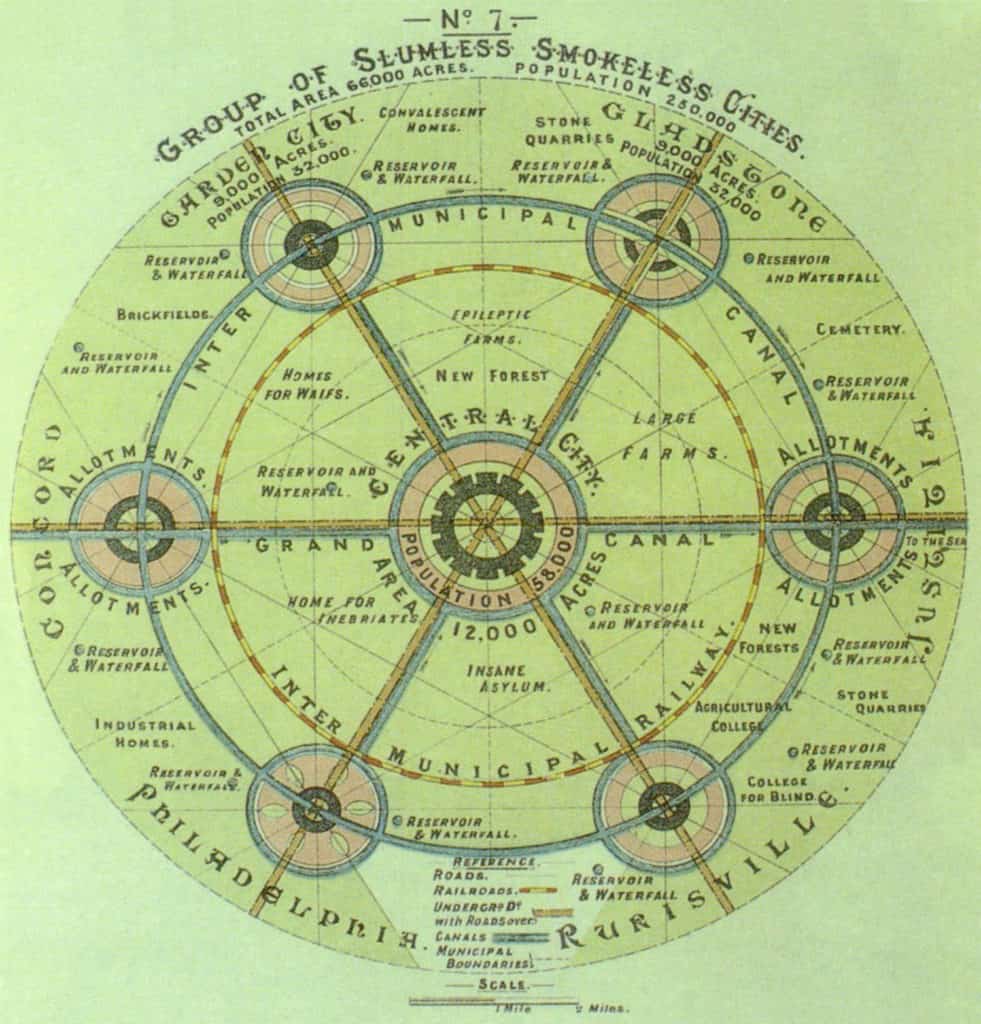

Modernism is a failure of normative theory, not scientific method. Ever since Robert Venturi published his twin polemics Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture/Learning from Las Vegas, it has been chic to assert that Modernism – and by implication, science – was responsible for the rape of our cities during the 20th century. A direct line can be drawn from the proliferation of late-20th/early-21st century suburban sprawl to Frank Lloyd’s Wright Broadacre City, and even further back to its infancy in Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City. However, like a DNA test freeing a falsely accused rapist, scientific method reveals the true culprit is, in fact, normative theory. The 20th century is a wasteland littered with normative theories: modernism, futurism, post-modernism, deconstructivism, traditionalism, neo-suburbanism and many more ‘-isms’ than we can enumerate. After the experience of the 20th century, it seems absurd to suggest we require more theoretical conjecture without scientific validation, more opinion and subjective observation – that is, less science – if we want to better understand the “organized complexity of our cities” (Jacobs, 1961). Sometimes it seems as if the planning profession and education has an adverse, knee-jerk reaction to anything it does not understand as “too theoretical”. Of course, the key to this sentence is not that it is “too theoretical” but rather that so many do “not understand” the proper role of science and theory in architecture and planning, in particular, and society, in general.

Science aspires to fact, not truth. The confusion about science is endemic to our society. You can witness it every time an atheist claims the non-existence of God on the basis of science. However, science does not aspire to truth. Not only is ‘Does God exist?’ unanswerable, it is a question any good scientist would never seek to answer in scientific terms. It is a question of faith. The value judgment we place on scientific fact does not derive from the science itself. It derives from the social, religious or cultural prism through which we view it.  Right or wrong is the purview of politicians, philosophers and theologians. There are plenty – perhaps too many – planners and architects analogous to politicians, philosophers and theologians and not enough of the scientific variety. And too often, those that aspire to science remain mired in the trap of normative theory and institutionalized dogma. The Modernist hangover lingers in our approach to theory. But we require less subjective faith in our conjectures and more objective facts to test them. We persist with models that are colossal failures. When we are stuck in traffic, we feel like rats trapped in a maze. We apply normative theory to how we plan our transportation networks and fail to test the underlining conjecture. The robust power of GIS to store and organize vast amounts of information into graphical databases is touted as transforming the planning profession. But those that don’t understand science, mistake a tool of scientific method for theory. We project population years and decades into the future, yet fail to return to these projections to test and expose their (in)validity, refine the statistical method and increase the accuracy of future projections. And we hide the scientific failings of our profession behind the mantra, “it’s the standard.”

Right or wrong is the purview of politicians, philosophers and theologians. There are plenty – perhaps too many – planners and architects analogous to politicians, philosophers and theologians and not enough of the scientific variety. And too often, those that aspire to science remain mired in the trap of normative theory and institutionalized dogma. The Modernist hangover lingers in our approach to theory. But we require less subjective faith in our conjectures and more objective facts to test them. We persist with models that are colossal failures. When we are stuck in traffic, we feel like rats trapped in a maze. We apply normative theory to how we plan our transportation networks and fail to test the underlining conjecture. The robust power of GIS to store and organize vast amounts of information into graphical databases is touted as transforming the planning profession. But those that don’t understand science, mistake a tool of scientific method for theory. We project population years and decades into the future, yet fail to return to these projections to test and expose their (in)validity, refine the statistical method and increase the accuracy of future projections. And we hide the scientific failings of our profession behind the mantra, “it’s the standard.”

We require analytical theory and objective knowledge. If the facts do not support our conjectures, then they need to be discarded. In normative theory, ideas are precious. In analytical theory, they are disposable in favor of a better conjecture on the way to a scientific proof. Scientific method is the means to test and validate or dispose of theory. Our profession and communities have paid a terrible price for the deployment of normative theory. However, quantitative observation and analysis of its failings has offered enlightenment about how to proceed confidently into the future. The work of notable researchers in Europe and the United States are leading the profession towards an analytical theory of the city. Even now, we will be able to deploy scientific method to derive better theory about the physical, social, economic and cultural attributes of the city. This leap forward will eventually propel planning out of the voodoo orbit of the social sciences and into the objective knowledge of true science. Until then, we need to focus a bit more on getting there and less time raising the SPECTRE of dead bogeymen to endorse the creation of entirely new ones.

Pixar Animation Studios was reaping the creative and financial benefits of a $485 million worldwide gross for Toy Story 2 so…

Pixar Animation Studios was reaping the creative and financial benefits of a $485 million worldwide gross for Toy Story 2 so… “There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email and iChat,” he said. “That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say ‘Wow.” and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.” So he had the Pixar building designed to promote encounters and unplanned collaborations. “If a building doesn’t encourage that, you’ll lose a lot of innovation and the magic that’s sparked by serendipity,” he said. “So we designed the building to make people get out of their offices and mingle in the central atrium with people they might not otherwise see…” “Steve’s theory worked from day one,” Lasseter recalled. “I kept running into people I hadn’t seen in months. I’ve never seen a building that promoted collaboration and creativity as well as this one.”

“There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email and iChat,” he said. “That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say ‘Wow.” and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.” So he had the Pixar building designed to promote encounters and unplanned collaborations. “If a building doesn’t encourage that, you’ll lose a lot of innovation and the magic that’s sparked by serendipity,” he said. “So we designed the building to make people get out of their offices and mingle in the central atrium with people they might not otherwise see…” “Steve’s theory worked from day one,” Lasseter recalled. “I kept running into people I hadn’t seen in months. I’ve never seen a building that promoted collaboration and creativity as well as this one.”

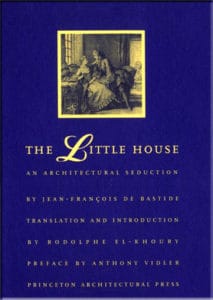

Despite Vidler’s heavily-jargon-weighed efforts to convince readers to assume a French Libertine perspective (an “alien culture”, according Vidler) in reading the text, The Little House actually reads like an appraisal of Tremicour’s worth as measured in his financial outlay on the house and the objects contained within; in this case, worth is a measure of taste that can be purchased. Vidler argues taste in the 18th century French sense is actually an aspect of touch (both literally and metaphorically, how we are physical and emotionally ‘touched’ by a person or thing). Vidler’s argument is not entirely convincing and it’s easy to wonder how the reader might react differently to the text in the absence of Vidler’s prefatory comments. Mélite’s conflicted feelings about Tremicour during her visit emerge, on one hand, from her distaste of the man and his reputation and, on the other, her appreciation of the liberating nature of his wealth in enabling him to obtain the best of things. This serves as an interesting contrast to Mélite, who is explicitly stated to have earned her taste through learning and experience (her age and wealth status are not mentioned though it’s safe to assume she is not a child and comes from a well-to-do French family). This seems to make Mélite’s dogged resistance to Tremicour’s (sometime clumsy) attempts at sexual seduction into a nature-nurture didactic whereby nature (one who is born with taste, i.e. Mélite) overcomes nurture (one who has purchased taste, i.e. Tremicour). Tremicour does have something of a nouveau riche quality about him, despite his title. However, this possible reading of the text is undercut by a revision to the ending of The Little House. According to el-Khoury’s notes, Mélite succeeded in her efforts to resist Tremicour’s attempted seduction in his petite maison and she retired to the country to recover from the ordeal in Bastide’s original ending. el-Khoury is unclear if Bastide himself changed the ending (i.e. original ending was in draft form) or if the translator has changed the ending using a 20th century perspective. Thus, The Little House ends with a threat, Mélite’s last words being “Tremicour, leave me! I do not want…”, and then brief acknowledgement of Tremicour’s success in seducing the virtuous girl. This revision is disturbing because it changes the tale from an architectural seduction into a libertine rape. The Little House thereby reasserts the purview of the masculine (of Tremicour, perhaps of the male contributors to this modern translation) over the feminine (of Mélite) in architecture and Mélite becomes, metaphorically-speaking, only another object to be collected. It is possible this review is skewed with a distinctive 21st century perspective about women but no matter how much some of us may wish to be a French Libertine, we are not.

Despite Vidler’s heavily-jargon-weighed efforts to convince readers to assume a French Libertine perspective (an “alien culture”, according Vidler) in reading the text, The Little House actually reads like an appraisal of Tremicour’s worth as measured in his financial outlay on the house and the objects contained within; in this case, worth is a measure of taste that can be purchased. Vidler argues taste in the 18th century French sense is actually an aspect of touch (both literally and metaphorically, how we are physical and emotionally ‘touched’ by a person or thing). Vidler’s argument is not entirely convincing and it’s easy to wonder how the reader might react differently to the text in the absence of Vidler’s prefatory comments. Mélite’s conflicted feelings about Tremicour during her visit emerge, on one hand, from her distaste of the man and his reputation and, on the other, her appreciation of the liberating nature of his wealth in enabling him to obtain the best of things. This serves as an interesting contrast to Mélite, who is explicitly stated to have earned her taste through learning and experience (her age and wealth status are not mentioned though it’s safe to assume she is not a child and comes from a well-to-do French family). This seems to make Mélite’s dogged resistance to Tremicour’s (sometime clumsy) attempts at sexual seduction into a nature-nurture didactic whereby nature (one who is born with taste, i.e. Mélite) overcomes nurture (one who has purchased taste, i.e. Tremicour). Tremicour does have something of a nouveau riche quality about him, despite his title. However, this possible reading of the text is undercut by a revision to the ending of The Little House. According to el-Khoury’s notes, Mélite succeeded in her efforts to resist Tremicour’s attempted seduction in his petite maison and she retired to the country to recover from the ordeal in Bastide’s original ending. el-Khoury is unclear if Bastide himself changed the ending (i.e. original ending was in draft form) or if the translator has changed the ending using a 20th century perspective. Thus, The Little House ends with a threat, Mélite’s last words being “Tremicour, leave me! I do not want…”, and then brief acknowledgement of Tremicour’s success in seducing the virtuous girl. This revision is disturbing because it changes the tale from an architectural seduction into a libertine rape. The Little House thereby reasserts the purview of the masculine (of Tremicour, perhaps of the male contributors to this modern translation) over the feminine (of Mélite) in architecture and Mélite becomes, metaphorically-speaking, only another object to be collected. It is possible this review is skewed with a distinctive 21st century perspective about women but no matter how much some of us may wish to be a French Libertine, we are not.