We the People… are not ready

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

I have been waiting for the appropriate time and place to ask a question. I wrote a tweet asking this question on the afternoon of the Boston Marathon bombing. However, I deleted the tweet without posting because 140 characters seemed woefully inadequate for any context to this question. I was also worried about prematurely discussing the implications before people had time to process Monday’s events. I wrote a slightly longer status update (about 40 words) for my personal Facebook page later that evening. I thought I could ask my friends this question. They know me and would willingly forgive any awkwardness arising from brevity. However, again, it seemed both premature and insufficient. I deleted the status update without posting. Thanks to the Amanda Erickson’s April 16th article, “A World Without Trash Cans?”, for Atlantic Cities (a link to her article is available below), I feel as if I have found the right venue to express something that has been bothering me… literally, for years. I ask this question and write this article with the disclaimer I am not a security expert. I am only a concerned citizen.

Here is the question: why didn’t anyone notice?

I lived in London from 1992-2000. During this time, like many Londoners, I had my fair share of close calls with Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombings.  My friends and I partied in a Soho pub called the Sussex Arms on a Saturday night. The next Saturday night, the IRA set off a nail bomb, killing one person, in the men’s room of the same pub. My aunt and uncle visited me in London. I eagerly showed them around the city on a beautiful spring day. The personal tour included visiting historical sites in the City of London. During this tour, we passed the Baltic Exchange on a couple of occasions. The next day, the IRA set off the bomb that destroyed the Baltic Exchange. The IRA set off three bombs on a Thursday along the same stretch of road my ex-wife and I walked every Saturday on the way to and from the grocery store. Of course, I was aware of new learned behaviors on my part while living in a city under siege by the IRA. This included being naturally suspicious of unattended bags and packages on the London Underground and elsewhere. After I returned home, I became aware of other learned behaviors. To this day, if I am walking along a street and see an unmarked parked van, I have to restrain myself from crossing the street to distance myself from a possible threat. The first time I realized I was doing this was in Palm Coast, Florida. I laughed at myself for subconsciously thinking the IRA might want to bomb Palm Coast. More importantly, it represented learned behavior from living in London for nearly a decade.

My friends and I partied in a Soho pub called the Sussex Arms on a Saturday night. The next Saturday night, the IRA set off a nail bomb, killing one person, in the men’s room of the same pub. My aunt and uncle visited me in London. I eagerly showed them around the city on a beautiful spring day. The personal tour included visiting historical sites in the City of London. During this tour, we passed the Baltic Exchange on a couple of occasions. The next day, the IRA set off the bomb that destroyed the Baltic Exchange. The IRA set off three bombs on a Thursday along the same stretch of road my ex-wife and I walked every Saturday on the way to and from the grocery store. Of course, I was aware of new learned behaviors on my part while living in a city under siege by the IRA. This included being naturally suspicious of unattended bags and packages on the London Underground and elsewhere. After I returned home, I became aware of other learned behaviors. To this day, if I am walking along a street and see an unmarked parked van, I have to restrain myself from crossing the street to distance myself from a possible threat. The first time I realized I was doing this was in Palm Coast, Florida. I laughed at myself for subconsciously thinking the IRA might want to bomb Palm Coast. More importantly, it represented learned behavior from living in London for nearly a decade.

There were others. I once had the unfortunate experience of watching a young woman throw herself under a London Underground train in a suicide attempt. It happened right in front of me. The young woman was standing a couple of feet to my right before she ran pass me and threw herself from the platform under the train. Fortunately, she survived with minor injuries. Afterwards, I realized she had been alone on the platform, coatless, and not carrying a bag. In the 1990s, almost everybody on the London Underground seemed to be carrying some sort of bag (briefcase, computer bag, backpack, shopping bag, and so on). They probably still do. From that point forward, when I was on the London Underground and I saw someone alone without a bag, I would casually stand near and in front of them, putting myself between them and the tracks, in an attempt to avoid repeating the experience. The probability this act made a difference was infinitely small. However, there was always the off-chance it might make a difference. It did not cost me anything to do and I seriously doubt anyone noticed a reason for my strategic positioning on the platform. I had developed a new learned behavior.

In the weeks after September 11, 2001, I visited English friends living in Atlanta, Georgia. Naturally, we discussed the events of September 11th within the context of our shared experience living in London with the constant threat of IRA terrorism. Make no mistake: the IRA were terrorists. They engaged in indiscriminate bombings designed to murder innocent civilians. This is the very definition of terrorism. In any case, my friends and I looked out the window of their downtown apartment in Atlanta, marveled about the neat row of trash cans spaced every 20 feet along the street, and wondered why they had not been removed. We talked about our travel experiences in the aftermath of September 11th. I admitted the presence of the National Guard armed with machine guns in American airports was comforting; not so much because of fear in the aftermath of September 11th but because it was more consistent with my European experience over the previous decade. My friends and I agreed that the United States was not ready if Al Qaeda decided to adopt IRA tactics. In the subsequent 12 years, this has been a source of occasional worry for me. I wondered, when is Al Qaeda (or any other terrorist group, foreign or domestic, organized or the proverbial ‘lone wolf’ fruitcake) going to realize how much damage they could really do by following the lead of the IRA? In 12 years, I have seen precious little to indicate we the people are ready for a sustained assault on thousands of the ‘soft targets’ across this country, designed to truly terrorize the general population on an everyday basis. Luckily, Al Qaeda and everyone else remained fixated of ‘spectacle terrorism’, designed to drive international news coverage into a feeding frenzy (terrorism by media proxy)… until Monday.

In the weeks after September 11, 2001, I visited English friends living in Atlanta, Georgia. Naturally, we discussed the events of September 11th within the context of our shared experience living in London with the constant threat of IRA terrorism. Make no mistake: the IRA were terrorists. They engaged in indiscriminate bombings designed to murder innocent civilians. This is the very definition of terrorism. In any case, my friends and I looked out the window of their downtown apartment in Atlanta, marveled about the neat row of trash cans spaced every 20 feet along the street, and wondered why they had not been removed. We talked about our travel experiences in the aftermath of September 11th. I admitted the presence of the National Guard armed with machine guns in American airports was comforting; not so much because of fear in the aftermath of September 11th but because it was more consistent with my European experience over the previous decade. My friends and I agreed that the United States was not ready if Al Qaeda decided to adopt IRA tactics. In the subsequent 12 years, this has been a source of occasional worry for me. I wondered, when is Al Qaeda (or any other terrorist group, foreign or domestic, organized or the proverbial ‘lone wolf’ fruitcake) going to realize how much damage they could really do by following the lead of the IRA? In 12 years, I have seen precious little to indicate we the people are ready for a sustained assault on thousands of the ‘soft targets’ across this country, designed to truly terrorize the general population on an everyday basis. Luckily, Al Qaeda and everyone else remained fixated of ‘spectacle terrorism’, designed to drive international news coverage into a feeding frenzy (terrorism by media proxy)… until Monday.

We have constructed a mammoth security bureaucracy to learn about and intercept terrorism threats before they cross our border and/or implement their plans. For the most part, it has been successful. However, I wonder how much of that success is due to terrorists’ unchanging focus on the uniquely spectacular instead of the ordinarily possible. It is true. We are an open society; in ideal, if not always in practice. And it is a good thing to aspire to this ideal, however imperfectly. But it does not mean we have to forgo common sense. Foolishness is not an inherent attribute of openness. At the same time, we do not want our home to become an armed military camp. Our approach to terrorism requires balance between freedom and caution, openness and common sense. After 12 years, we still do not seem to be striking the right balance. It is too top-heavy. Our government bureaucracies are well prepared, perhaps overly so, and (seemingly) paranoid. Our citizens are under-prepared and (seemingly) nonchalant. It is puzzling how two unattended bags can escape the notice of dozens, perhaps hundreds, of people in Boston. All it took to avert this event was one or two people, ordinary citizens, flagging down a police officer or event organizer after noticing a suspicious package along the marathon route. Why did this not happen?  It is time ordinary citizens became more vigilant, to develop learned behaviors that, in themselves, might prove equally effective in guarding against acts of terrorism. After all, as big as the government is, there are still more of us citizens than government bureaucrats. The most effective act against terrorism on September 11, 2001 was not a presidential decision, government policy, or military action. It was an act of vigilance and bravery by ordinary citizens on United Flight 93. Ordinary citizens appear to have learned this lesson in the air. Isn’t about time we learned the same lesson on the ground?

It is time ordinary citizens became more vigilant, to develop learned behaviors that, in themselves, might prove equally effective in guarding against acts of terrorism. After all, as big as the government is, there are still more of us citizens than government bureaucrats. The most effective act against terrorism on September 11, 2001 was not a presidential decision, government policy, or military action. It was an act of vigilance and bravery by ordinary citizens on United Flight 93. Ordinary citizens appear to have learned this lesson in the air. Isn’t about time we learned the same lesson on the ground?

In asking who did this and why, I think we are missing an equally important question, which is: why didn’t anyone notice? I am worried that we are still not ready for this kind of terrorism… and, by now, we really should be.

A World Without Trash Cans? | Amanda Erickson | The Atlantic Cities.

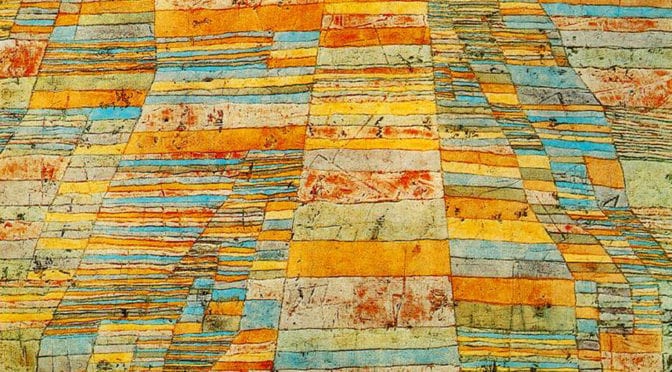

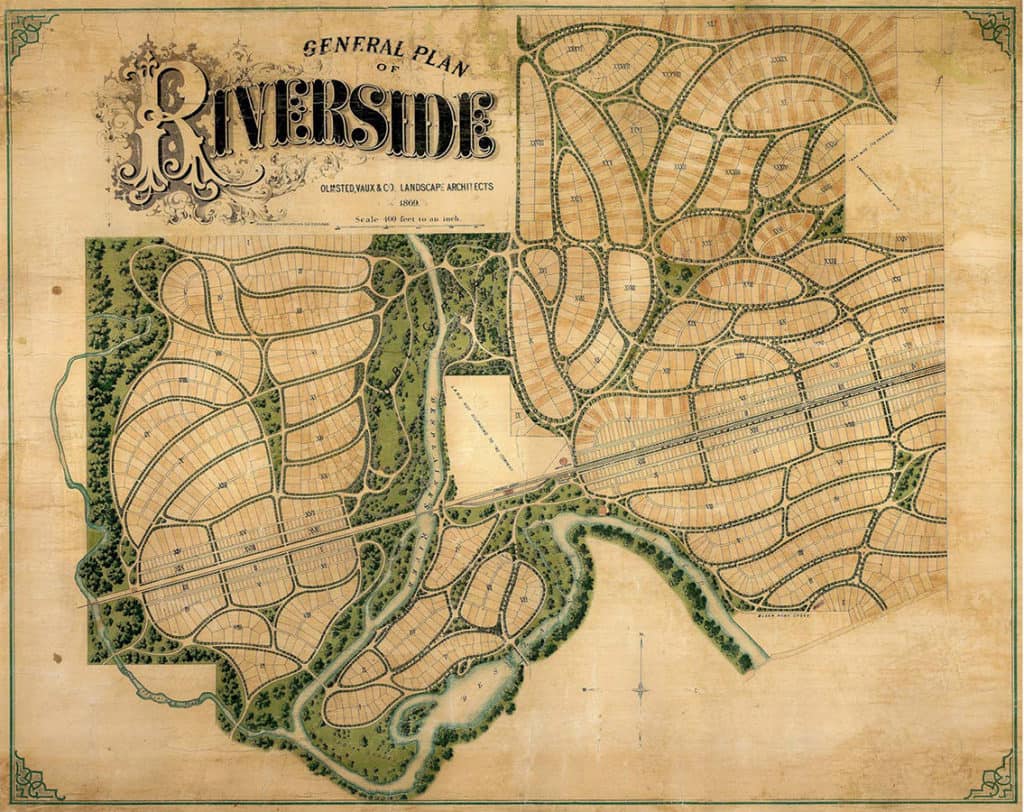

Perhaps skewed by an American perspective towards the land, it might suggest terre potentiel (the potential of the land). Humans have already intervened in the landscape for agricultural uses and the river already serves as a transportation hub, both associated with the support mechanisms for urban living. “In this pattern of fields, all is order, timeless structure, with a poetic element added… in twentieth-century creative language” (Source: PaulKlee.net). It is in this ‘timeless structure of order’ that can be found the design traces of a future urban pattern, a future city that has yet to emerge from the land but the potential for its emergence is already etched in the landscape. I love this painting, not so much for what it represents in the ‘here and now’ (though it is beautiful only on these terms) but what it represents about the possible, the “undiscovered country,” …the future, where all travelers must venture but none may journey before it is time.

Perhaps skewed by an American perspective towards the land, it might suggest terre potentiel (the potential of the land). Humans have already intervened in the landscape for agricultural uses and the river already serves as a transportation hub, both associated with the support mechanisms for urban living. “In this pattern of fields, all is order, timeless structure, with a poetic element added… in twentieth-century creative language” (Source: PaulKlee.net). It is in this ‘timeless structure of order’ that can be found the design traces of a future urban pattern, a future city that has yet to emerge from the land but the potential for its emergence is already etched in the landscape. I love this painting, not so much for what it represents in the ‘here and now’ (though it is beautiful only on these terms) but what it represents about the possible, the “undiscovered country,” …the future, where all travelers must venture but none may journey before it is time. About Paul Klee

About Paul Klee

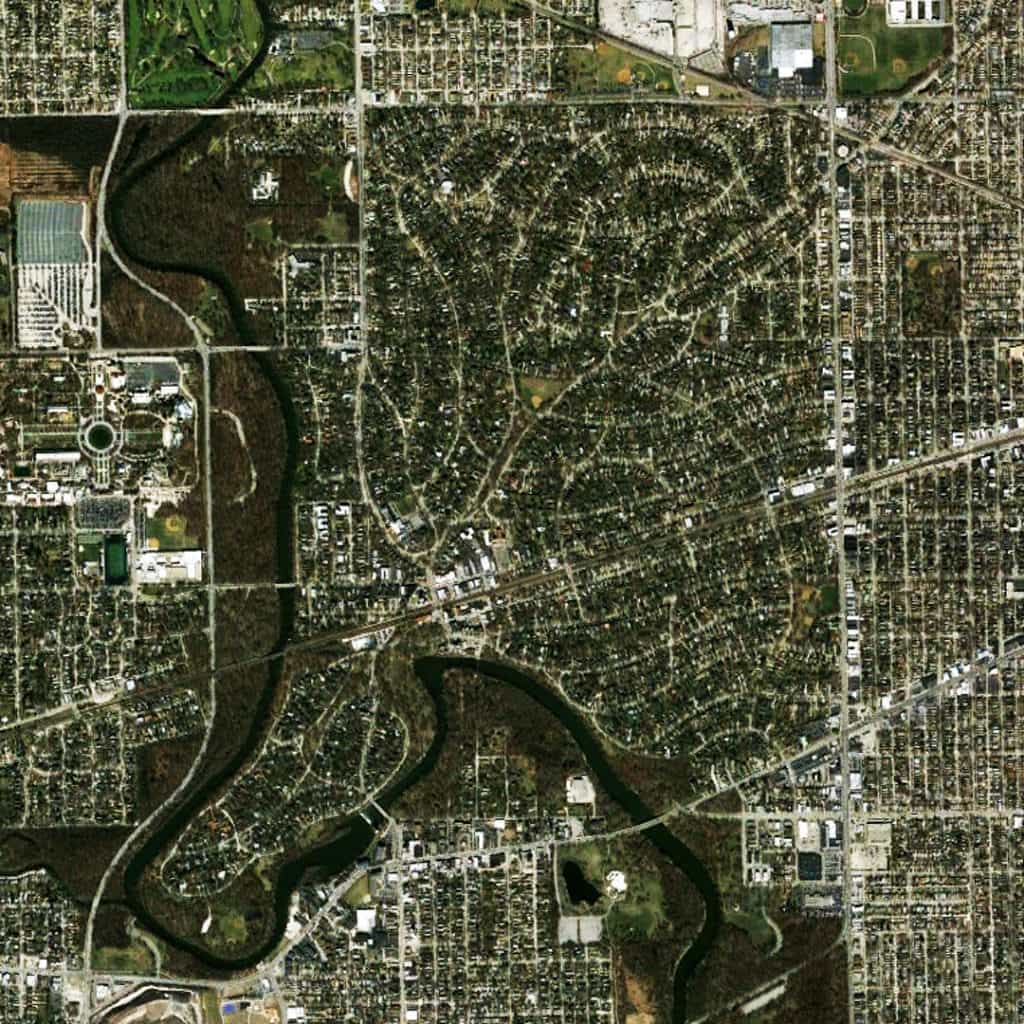

For example, they generally discuss what they describe as “Landscape Urbanism” without much detail. They are far too kind to reveal what, I suspect, is probably an outright disdain for this approach to serious urban problems. Landscape Urbanism only exists because it is politically expedient and offers policy makers/politicians the appearance of doing something (and feeds the financial coffers of consultants) when, in fact, it is usually a useless solution that avoids the real problem all together. What is really interesting about their historical analysis is where industrial land uses were not located; namely, along the riverfront at the edge of the Woodward plan. This suggests the seeds of Detroit’s urban decline might be traced back to the early 19th century. Large-scale industrial land uses may not have been allowed to develop along the riverfront of the Woodward plan. If the industrial land uses along Davison/Grand had come to be located along the riverfront instead of the northern periphery, Detroit may have been better positioned to manage its transition from an industrial to a post-industrial city, as other cities have accomplished to varying degrees of success.

For example, they generally discuss what they describe as “Landscape Urbanism” without much detail. They are far too kind to reveal what, I suspect, is probably an outright disdain for this approach to serious urban problems. Landscape Urbanism only exists because it is politically expedient and offers policy makers/politicians the appearance of doing something (and feeds the financial coffers of consultants) when, in fact, it is usually a useless solution that avoids the real problem all together. What is really interesting about their historical analysis is where industrial land uses were not located; namely, along the riverfront at the edge of the Woodward plan. This suggests the seeds of Detroit’s urban decline might be traced back to the early 19th century. Large-scale industrial land uses may not have been allowed to develop along the riverfront of the Woodward plan. If the industrial land uses along Davison/Grand had come to be located along the riverfront instead of the northern periphery, Detroit may have been better positioned to manage its transition from an industrial to a post-industrial city, as other cities have accomplished to varying degrees of success.

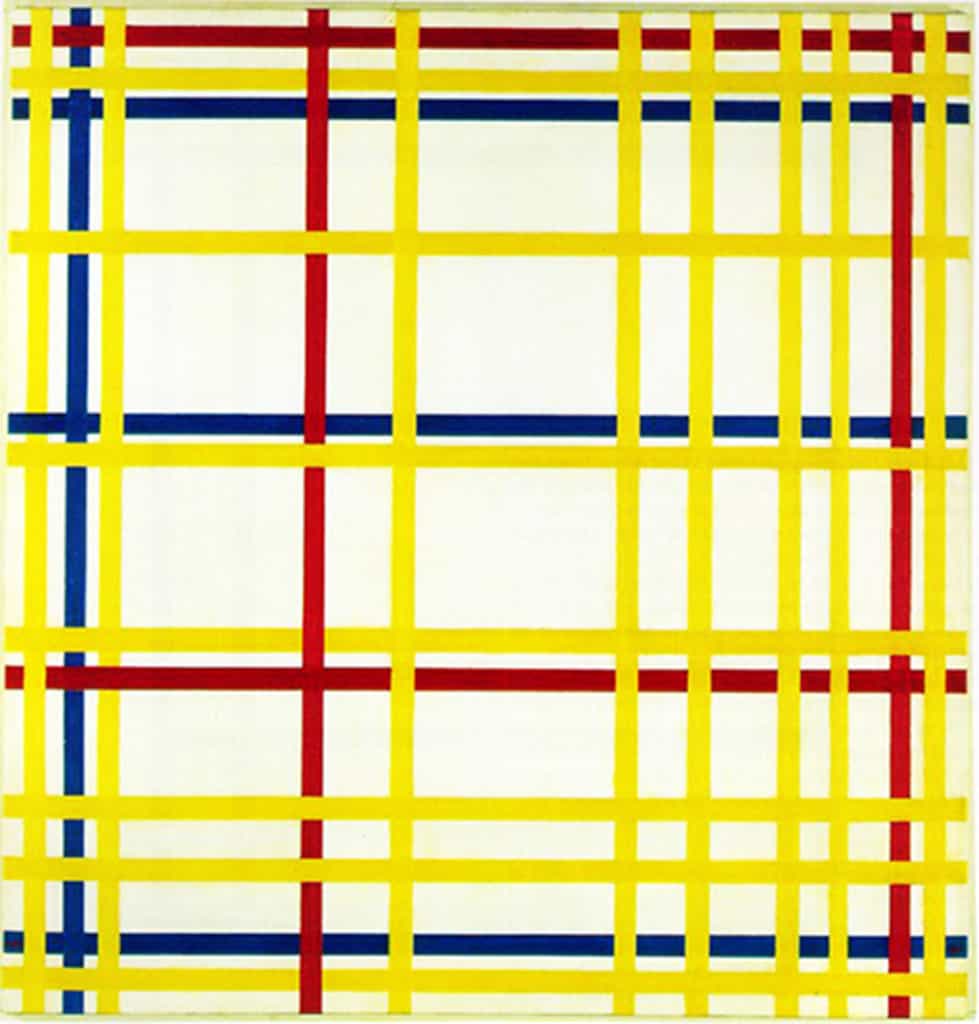

These white shapes could also be interpreted as ‘windows’ into those spaces. In this sense, Mondrian is playing with the two-dimensional plane of the canvas (a recurring motif of 20th-century representations of the city) to not only abstract but also ‘compress’ the abstraction of built space in the city. Given the De Stijl artists’ preference for universality in their abstractions, this latter interpretation might actually be closer to Mondrian’s original vision for the painting since the ‘vertical’ interpretation would be universal to all cities whereas the ‘horizontal’ one tends to be particular to New York and American cities in general. Mondrian’s New York City I builds upon and works within the artistic principles and framework outlined by Mondrian himself for the De Stijl movement, first reaching fruition in 1920 with Composition A: Composition with Black, Red, Gray, Yellow, and Blue. We will see some additional examples of Mondrian’s work in later issues of The City in Art.

These white shapes could also be interpreted as ‘windows’ into those spaces. In this sense, Mondrian is playing with the two-dimensional plane of the canvas (a recurring motif of 20th-century representations of the city) to not only abstract but also ‘compress’ the abstraction of built space in the city. Given the De Stijl artists’ preference for universality in their abstractions, this latter interpretation might actually be closer to Mondrian’s original vision for the painting since the ‘vertical’ interpretation would be universal to all cities whereas the ‘horizontal’ one tends to be particular to New York and American cities in general. Mondrian’s New York City I builds upon and works within the artistic principles and framework outlined by Mondrian himself for the De Stijl movement, first reaching fruition in 1920 with Composition A: Composition with Black, Red, Gray, Yellow, and Blue. We will see some additional examples of Mondrian’s work in later issues of The City in Art. About Piet Mondrian

About Piet Mondrian