Think Different, Be “Insanely Great”

Think Different, Be “Insanely Great”

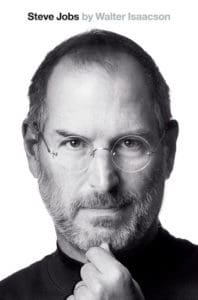

BOOK REVIEW of Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

by Mark David Major, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

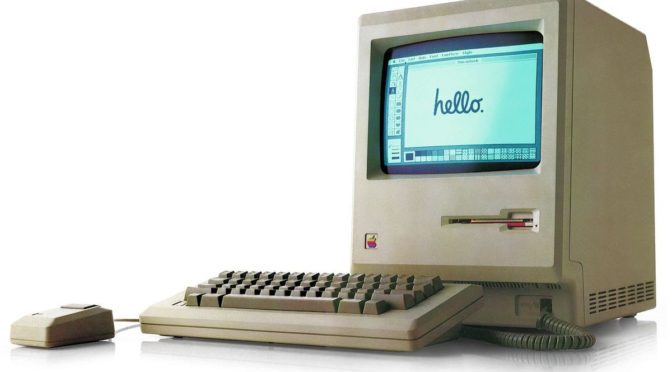

FULL DISCLOSURE: I am writing this review on my MacBook Pro with Retina Display with my iPhone and iPad Mini sitting near at hand while I listen to a shuffle of classical music in my iTunes Library. When I started writing this disclosure paragraph, I noticed my apps were syncing to all of my devices via iCloud, which finished well before I had completed this paragraph. I have been an unapologetic member of the Apple Cult since 1993.

A few times in Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, the biographer and his subject admit there will be a lot that Jobs won’t like in this authorized biography. Once again, Steve Jobs was right. Isaacson’s biography is not a great product. The writing is often repetitive, even diverging into triviality on occasion, with the biographer/interviewees (except Jobs himself) all too eager to engage in ‘Dime Store’ Freudian psychoanalysis about the book’s subject. At 656 pages, Isaacson’s biography would have benefited from the same zeal for simplicity and minimalism (in terms of editing) that characterized so many of Apple’s products during Jobs’ two tenures at the company. In fact, Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson reads like Simon & Schuster rushed the book to market months ahead of schedule so it could financially capitalize on Jobs’ death in late 2011. The release date is a mere two weeks after Jobs death on October 5, 2011. This is something Jobs would have never tolerated while he was alive. Isaacson’s biography is not a bad book but it could have been “insanely great” like its subject.  There are many useful, some wonderful insights (usually originating from Jobs himself) contained within, so it is well worth your time to read. In the end, what shines through in the book, despite its problems, is the genius and greatness of Steve Jobs.

There are many useful, some wonderful insights (usually originating from Jobs himself) contained within, so it is well worth your time to read. In the end, what shines through in the book, despite its problems, is the genius and greatness of Steve Jobs.

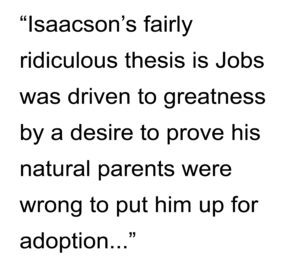

Isaacson’s fairly ridiculous thesis is Jobs was driven to greatness by a desire to prove his natural parents were wrong to put him up for adoption, which begs the question why there aren’t more industry leaders with adoptive parents. Jobs is fairly dismissive of this line of thought. Isaacson’s equally ridiculous aim is to get his subject to admit, “He is an asshole.” We are all angels and assholes (some, more one than other). It is called being human so it’s unclear why this is important. Jobs was a perfectionist but he never (thankfully) claimed he was perfect. Many of Jobs management techniques are tried, tested and effective even if Jobs’ form of brutal honesty lacked a ‘politeness’ filter. Anyone successful, who has been in a leadership position, will recognize these techniques.

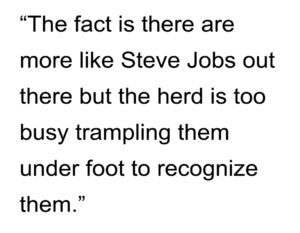

Isaacson devotes a considerable amount of words to Jobs’ tendency to construct a “reality distortion field”, an ability to weld or ignore reality to his wishes but also compel designers and engineers to do the seemingly impossible. We all construct “reality distortion fields” in an attempt to warp reality to our wishes. Some are more successful and ambitious at it than others. It is unclear why Isaacson finds this distinctive human trait so compelling other than the fact Jobs changed the reality of the way things work in this world. The fact is there are many people in the world, who simply cannot abide greatness in their presence. They seek to bring genius down to their level, a sort of “stupidity distortion field.” Jobs would describe this as Grade C people bringing down the Grade A people around them to the average, “the ugly”, or the “totally shit”. Isaacson could easily devote an entire book to how otherwise seemingly intelligent people (like Bill Gates, who comes across as a decent and pleasant schmuck but a schmuck nonetheless) adopt stupid arguments, decisions, and positions to distort the greatness or genius of individuals around them. The fact is there are more like Steve Jobs out there but the herd is too busy trampling them under foot to recognize them. In the end, Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson is best when all aspects of Jobs (the good and the bad) filter through the biographer’s gaze.  Was Steve Jobs perfect? No, he was human. Personally, I never asked for Apple products to be perfect. I only asked that Apple products be the best in the world and, usually, they were. I never asked Steve Jobs to be anything than what he was: a brilliant businessman, an insight artist, and a (sometimes) source and (often) shepherd of technological innovation. In the end, what was remarkable about Steve Jobs was not that he changed the world but he changed the world in the face of the ‘conventional wisdom’, which is often polite code for the stupidity of the consensus. Frankly, I prefer to live in Jobs’ reality. Along the way, he lived a remarkable life. Surely, that is enough. The world seems smaller without Steve Jobs in it. We have Jobs’ Apple to thank for it but it is also a testament to the legacy of Steve Jobs. He will be missed.

Was Steve Jobs perfect? No, he was human. Personally, I never asked for Apple products to be perfect. I only asked that Apple products be the best in the world and, usually, they were. I never asked Steve Jobs to be anything than what he was: a brilliant businessman, an insight artist, and a (sometimes) source and (often) shepherd of technological innovation. In the end, what was remarkable about Steve Jobs was not that he changed the world but he changed the world in the face of the ‘conventional wisdom’, which is often polite code for the stupidity of the consensus. Frankly, I prefer to live in Jobs’ reality. Along the way, he lived a remarkable life. Surely, that is enough. The world seems smaller without Steve Jobs in it. We have Jobs’ Apple to thank for it but it is also a testament to the legacy of Steve Jobs. He will be missed.

I’m attaching video links to a couple of seminal moments in the life of Steve Jobs. First, the famous 1984 MacIntosh commercial, directed by Ridley Scott, which aired during the Super Bowl (above in the body of the review). Many in the trade (including TV Guide) say it is the greatest commercial ever. Second, is the famous commencement address Jobs gave at Stanford University in 2005 (see below). Remember: think different.

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster

Hardcover, 656 pages

Available from Amazon here.

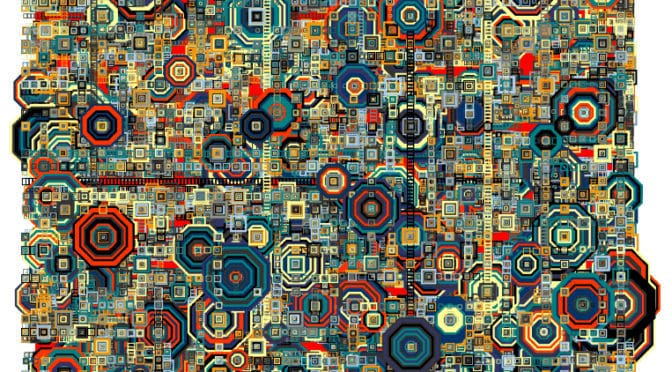

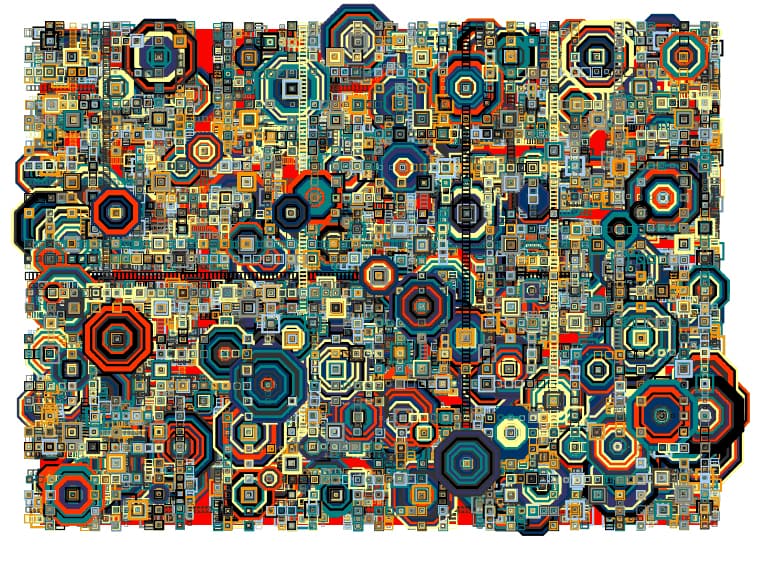

I am not even going to pretend to understand the mathematics of what Relyea is describing, except in only the vaguest sense. I’m sure Dr. Nick “Sheep” Dalton and Dr. Ruth Conroy Dalton would understand the mathematics of Relyea’s generative algorithm, and I will get them to explain it to me the next time I see them. For those interested in the mathematics of the algorithm, there is more information available

I am not even going to pretend to understand the mathematics of what Relyea is describing, except in only the vaguest sense. I’m sure Dr. Nick “Sheep” Dalton and Dr. Ruth Conroy Dalton would understand the mathematics of Relyea’s generative algorithm, and I will get them to explain it to me the next time I see them. For those interested in the mathematics of the algorithm, there is more information available  About Don Relyea

About Don Relyea

About Kathleen Patrick

About Kathleen Patrick

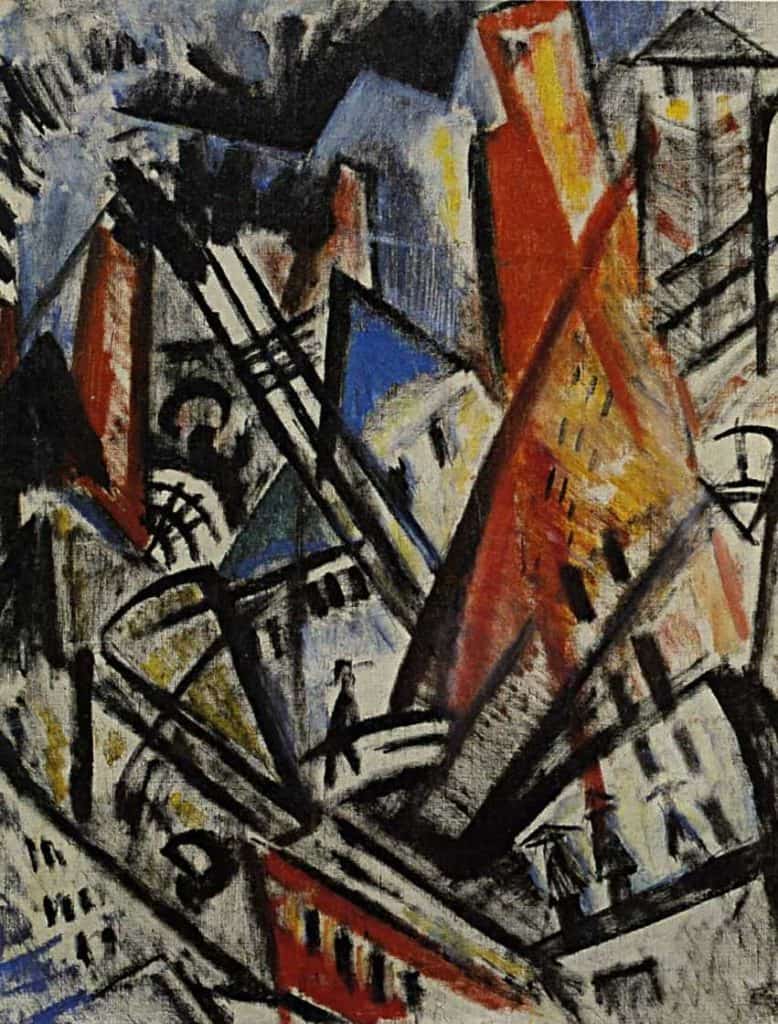

Olga Rozanova’s City (1916) is a wonderful abstract painting, which takes the city as its subject. Her city is all kinetic energy, the canvas almost ‘alive’ with movement. Her painting builds on the Cubist tendency to compress time and space into a single glance at a subject, which conveys a plenitude of information to the viewer. This, in itself, builds on the earlier Impressionist technique, which included movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience in the painting. However, in the case of Cubism, it is not the movement of human perception that depicted in the painting but rather the movement and energy inherent in the subject itself across time and space, which is both compressed and captured in the representation. Olga Rozanova’s City is a brilliant look at

Olga Rozanova’s City (1916) is a wonderful abstract painting, which takes the city as its subject. Her city is all kinetic energy, the canvas almost ‘alive’ with movement. Her painting builds on the Cubist tendency to compress time and space into a single glance at a subject, which conveys a plenitude of information to the viewer. This, in itself, builds on the earlier Impressionist technique, which included movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience in the painting. However, in the case of Cubism, it is not the movement of human perception that depicted in the painting but rather the movement and energy inherent in the subject itself across time and space, which is both compressed and captured in the representation. Olga Rozanova’s City is a brilliant look at

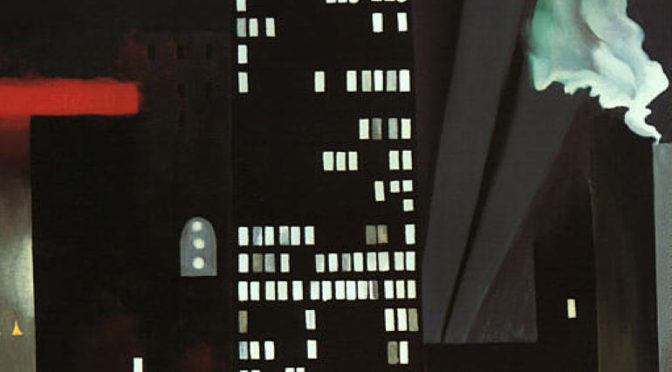

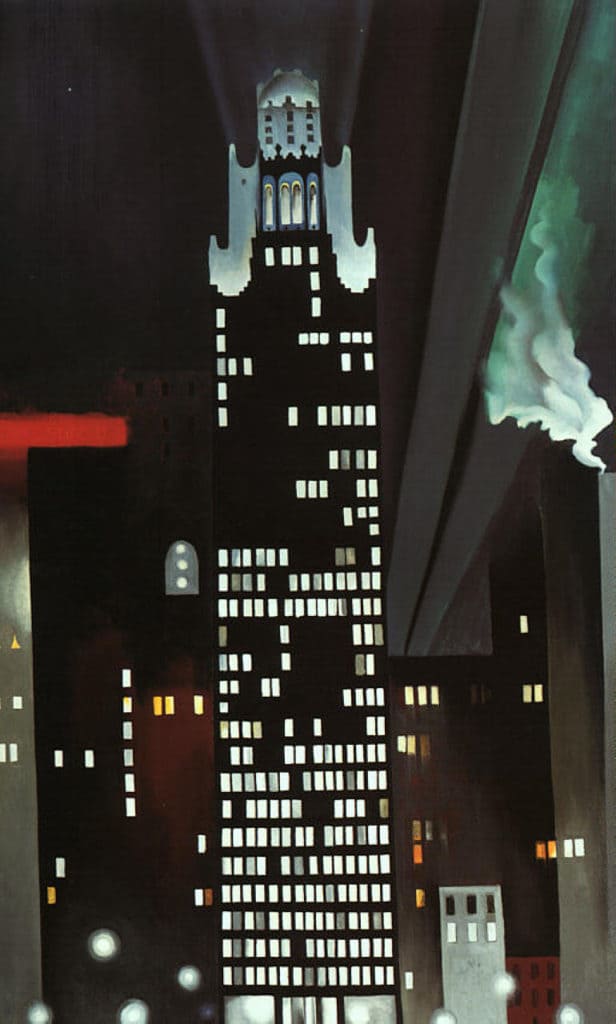

We can say this with some confidence because if you were to remove all of the ‘painted light’ from this painting, only a black canvas would remain. It is this ‘painted light’ that provides a subtle richness and contextual depth to the best of O’Keeffe’s cityscape paintings. Later, we will see more explicit examples in her other paintings, for example in The Shelton with Sunspots (1926). In this sense, the subject is the artifice of form emerging from the arrangement of light. The fact the words ‘Radiator Building’ and ‘New York’ are in the title of the painting is completely inconsequential and accidental to the subject of the piece. It is also misleading on O’Keeffe’s part by naming the painting in this manner. However, this is completely consistent with her tendency to be opaque when it comes to the subject matter of her own paintings. As architects and planners, O’Keeffe’s painting shows us how we can expand our perception of the city beyond the conventional (form) to see its richness in other, more subtle – and, perhaps, richer – ways (light).

We can say this with some confidence because if you were to remove all of the ‘painted light’ from this painting, only a black canvas would remain. It is this ‘painted light’ that provides a subtle richness and contextual depth to the best of O’Keeffe’s cityscape paintings. Later, we will see more explicit examples in her other paintings, for example in The Shelton with Sunspots (1926). In this sense, the subject is the artifice of form emerging from the arrangement of light. The fact the words ‘Radiator Building’ and ‘New York’ are in the title of the painting is completely inconsequential and accidental to the subject of the piece. It is also misleading on O’Keeffe’s part by naming the painting in this manner. However, this is completely consistent with her tendency to be opaque when it comes to the subject matter of her own paintings. As architects and planners, O’Keeffe’s painting shows us how we can expand our perception of the city beyond the conventional (form) to see its richness in other, more subtle – and, perhaps, richer – ways (light).