Stay tuned to The Outlaw Urbanist for more information and release dates!

Publications by The Outlaw Urbanist blogger, Mark David Major.

The Spectre of the Ultimate Green Building

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist Contributor

Imagine the ultimate sustainable green building… housing hundreds, perhaps thousands of people, drawing on geothermal power as an almost inexhaustible source of energy, and constructed to use the Earth itself to provide a natural means of cooling. This building is the very ideal of “Gizmo Green”, as defined by Steve Mouzon, since it draws upon cutting edge technological advances to provide ecological solutions. This magnificent building of our imagination even has its own light rail transit system. However, it also has a distinctly anti-urban quality about it.  It can only be found in exurban locations, i.e. near to an urban location but not too close. Somehow, it reconciles an inherently contradictory nature into its very function. In short, this magnificent green building is all things to all people.

It can only be found in exurban locations, i.e. near to an urban location but not too close. Somehow, it reconciles an inherently contradictory nature into its very function. In short, this magnificent green building is all things to all people.

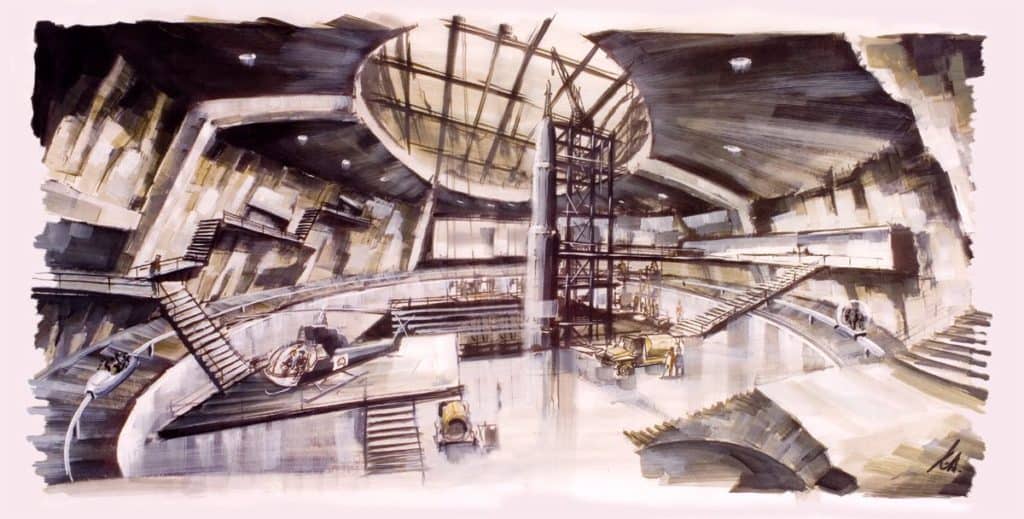

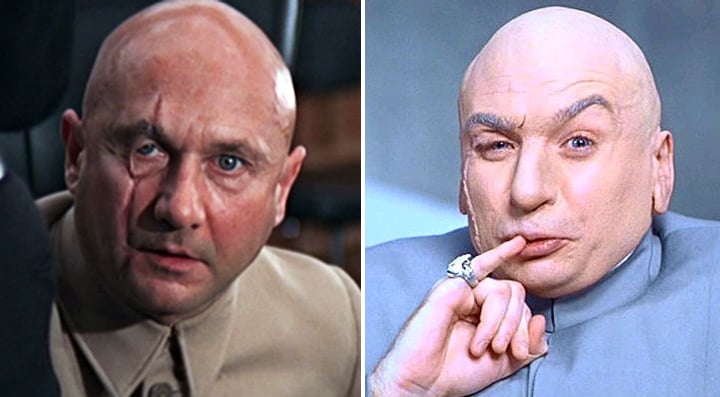

Can such a green building really be imagined? It already has; it is Ernst Stavo Blofeld’s underground volcano lair in You Only Live Twice (1967).

Blofeld’s lair was built in a dormant volcano so presumably draws on geothermal power for energy. It was also built underground so the building uses the Earth itself to provide natural cooling for its interior. In the film, we see hundreds of Blofeld’s minions in the lair but presumably its capacity is much larger than portrayed… or the film’s budget would allow in terms of extras. The building even has its own small-scale light rail system as well as a helipad and space launch pad! The design also appears, in part, to draw upon Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon in terms of visual surveillance. This is likely necessary since paranoia is a fundamental aspect of Blofeld’s autocratic power in the Bond films. The design of Blofeld’s underground volcano lair was Michael Myers’ satirical inspiration for Dr. Evil’s ‘secret’ volcano lair in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999). It is fair to conclude the specifications for Dr. Evil’s lair were much the same as Blofeld’s in You Only Live Twice.

Blofeld and Dr. Evil are not the only ‘Bond’ villains to dabble in radical environmentalism. Karl Stromberg in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) attempts to manipulate the United States and Soviet Union into launching global nuclear war while he is safely secluded in his underwater lair, Atlantis, with a chosen few to rebuild human civilization after the holocaust. Stromberg is a marine scientist who implicitly – and paradoxically – appears to have a radical environmentalist agenda. We say ‘paradoxically’ because his plan involves plunging the Earth into Nuclear Winter. His underwater lair, Atlantis, off the coast of Sardinia appears to draw on many of the same design specifications for Blofled’s lair with some modifications, i.e. drawing upon underwater thermal vents for energy, using the Mediterranean Sea for natural cooling of the structure, and so on.  In the follow-up film, Moonraker (1979), the villain Hugo Drax explicitly engages in large-scale eco-terrorism by hatching a scheme to release a viral toxin on the Earth, which will destroy all human life but leave unharmed all other plant and animal life. Drax takes the position of environmentalists to their logical – and inevitable – conclusion, which is the Earth would be better off without any human beings. Drax attempts to implement his dastardly plan while safely secluded in his moon base lair (also Michael Myers’ satirical inspiration for Dr. Evil’s moon base lair in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me). Finally, the Bond villain in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), Francisco Scaramanga, uses solar power for energy at his small-scale lair (in comparison to the Blofeld, Stromberg, and Drax hideouts) on an island in the South China Sea.

In the follow-up film, Moonraker (1979), the villain Hugo Drax explicitly engages in large-scale eco-terrorism by hatching a scheme to release a viral toxin on the Earth, which will destroy all human life but leave unharmed all other plant and animal life. Drax takes the position of environmentalists to their logical – and inevitable – conclusion, which is the Earth would be better off without any human beings. Drax attempts to implement his dastardly plan while safely secluded in his moon base lair (also Michael Myers’ satirical inspiration for Dr. Evil’s moon base lair in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me). Finally, the Bond villain in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), Francisco Scaramanga, uses solar power for energy at his small-scale lair (in comparison to the Blofeld, Stromberg, and Drax hideouts) on an island in the South China Sea.

Indeed, a strong radical environmentalism strain appears to be common to many of the most-noteworthy ‘Bond’ villains, more so than one might expect at first glance. Putting aside the issues of international nuclear terrorism and blackmail, counter-intelligence, terrorism, revenge, and extortion (the “Special Executive for…”, i.e. S.P.E.C.T.R.E.), it is a legitimate question to ask whether ‘Bond’ villains represent some sort of ideal model for environmental protectionism in the world today. Is this the future of an Environmental Protection Agency and other government/non-governmental entities gone mad with power and their own narrow agenda? Are Ernst Stavo Blofeld and Dr. Evil the future faces of radical environmentalism?

Of course, in the end, James Bond and Austin Powers always defeat the villain. In contrast to the radical environmentalist strain of these villains, Bond and Powers are the ultimate urbane individualists. Powers lives in a bachelor pad (depending on the film and time period, above Piccadilly Circus or on the South Bank in central London). Bond apparently lives in a central London row house, presumably in the Bloomsbury or Chelsea neighborhood judging from an early scene in Live and Let Die (1973). Perhaps Bond even lives next door to Patrick McGoohan’s “Number Six.” Is there a Spy Row a couple of blocks over from Saville Row in London? In any case, in the end, the traditional urbanist always defeats the radical environmentalist to save the day and the world… and get the girl.

Updated: December 11, 2012

Bumper Sticker Paradigms

An Editorial by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

Day-to-day, many of you will have probably seen the above bumper sticker. Perhaps some of you even have this bumper sticker on your car. It is an amusing and sarcastic – albeit cheap – political shot from the political left against the political right’s concerns about budget deficits and the national debt in the United States. For the record, we are talking about an annual Federal budget deficit of more than $1 Trillion Dollars ($1,000,000,000,000) over the last 4 years, and now almost $16 Trillion Dollars ($16,000,000,000,000) of total debt accumulated by the Federal government (more than 100% of the 2012 Gross Domestic Product, i.e. GDP). Incidentally, almost a third of the national debt was raided from and is now owed to the Social Security Trust Fund. On top of this, there are some (cautious) estimates that the Federal, State and local governments in the United States has more than $55 Trillion Dollars ($55,000,000,000,000) in total unfunded liabilities.  The point is estimates vary from worse to even worse. Anyone who does not treat the collective debt burden of the United States with the greatest concern is a fool, a liar, or a Nobel-winning economist working for the New York Times.

The point is estimates vary from worse to even worse. Anyone who does not treat the collective debt burden of the United States with the greatest concern is a fool, a liar, or a Nobel-winning economist working for the New York Times.

However, this editorial is actually not about debt and deficits. It is about the insidious message this bumper sticker conveys for urbanism in the United States, once we dig a little deeper beneath the superficial sarcasm of the message itself to the paradigm hiding underneath. What do we mean?

First, the message is explicitly about “paved roads.” It is not about the value of roads in general. Indeed, a key aspect of the sarcasm contained in the message lies in the fact that the bumper sticker is readable while you are driving your car, i.e. “isn’t it nice to have a smooth ride on this paved road so you can read my amusing bumper sticker?” Now, of course, not all paved roads necessarily have to be asphalt or concrete roads. For example, cobblestones and brick roads are also paved roads; even the Land of Oz had its yellow and red brick roads. However, such road surfaces rarely qualify as a ‘smooth ride’, especially over the lifetime of that road. Such roads are not conducive to mobile reading, especially for those of us prone to motion sickness. It is fair to conclude that most people will understand the reference to paved roads in the bumper sticker to mean asphalt or concrete roads. After all, most road surfaces in the United States are paved asphalt or concrete and this will constitute most people’s everyday experience of paved roads.

The minimal graphic design of the rudimentary lane striping in the bumper sticker also suggests “paved” is an implicit reference to only asphalt or concrete roads. Alternatively, the graphic design and elongated shape of the “Paved Roads” portion at the top of the bumper sticker could be interpreted as a rudimentary road construction sign, which every American will have experienced; extensively and usually regretfully so in urban areas. More importantly, either interpretation is appropriate to the message itself because this is not how anyone would choose to typically represent an alternative surface such as brick or cobblestone for a paved road. There should not be any doubt that the design of the bumper sticker is both simple and excellent, which is usually the best kind of graphic design.

The paradigm underlying the message should be important to any professional urban designer, planner, traffic engineer, or knowledgeable layman because it explicitly favors impervious road surfaces. For the uninitiated, this means such road surfaces are impenetrable to stormwater, seals the soil surface and eliminate rainwater infiltration and natural groundwater recharge, collect solar heat in their dense mass and when that heat is released, raises air temperatures.  More importantly, the lack of rainwater infiltration makes impervious surfaces the ‘carriers’ for non-point pollution sources. Non-point sources typically means rainwater falling on the asphalt shingles of you house, from there to the lawn with fertilizers and pesticides (or, in some areas, septic tanks), from there to the road into the stormwater sewer system, and usually directly into a nearby water body without any treatment. If you want more pollution, then you want more impervious road surfaces, i.e. precisely the type of “paved roads” this bumper sticker is referencing. Irony has never been an especially strong point of the political left in the United States so it is doubtful that progressives and liberals appreciate the fundamentally anti-environmental message of the bumper sticker on their car (probably a gas-guzzling SUV anyway). The irony, of course, is radical environmentalism has been a mainstay of the political left in the United States since the 1960s.

More importantly, the lack of rainwater infiltration makes impervious surfaces the ‘carriers’ for non-point pollution sources. Non-point sources typically means rainwater falling on the asphalt shingles of you house, from there to the lawn with fertilizers and pesticides (or, in some areas, septic tanks), from there to the road into the stormwater sewer system, and usually directly into a nearby water body without any treatment. If you want more pollution, then you want more impervious road surfaces, i.e. precisely the type of “paved roads” this bumper sticker is referencing. Irony has never been an especially strong point of the political left in the United States so it is doubtful that progressives and liberals appreciate the fundamentally anti-environmental message of the bumper sticker on their car (probably a gas-guzzling SUV anyway). The irony, of course, is radical environmentalism has been a mainstay of the political left in the United States since the 1960s.

What about the second part of the message, i.e. “another fine example of unnecessary government spending?” This is also rich with irony in undercutting the superficial message the political left is trying to convey to voters. The power of the message exclusively relies on the reader being uninformed. Most roads in the United States (in gross terms, not total linear miles) are residential streets. The private sector builds most of these roads including many arterial and collector roads to support a plethora of suburban subdivisions. Developers later convey ownership of these arterial (and some collector) roads to public agencies for maintenance purposes. However, these days most of the residential roads remain private roads, which non-governmental agencies such as homeowners associations, neighborhood groups, or community development districts maintain on behalf of their residents. Developers always pass on the cost of constructing the roads to their customers in the price of your home. HOA usually pass on the cost of maintaining the roads in their community to their residents through HOA fees, etc.

The government does build and maintain roads, the interstate highway system being the most obvious example most commonly cited by both the political left and right in the United States. However, most government revenue for capital improvements comes from the taxpayers via user fees and taxes on income or property. In this sense, because the private and public sector always passes the costs of all road construction to you in the price of your home or the taxes you pay to the government, all roads are ‘public’ roads. When it comes to roads, we really did build that…

…Or, more accurately, we paid for it even if we did not need or want that road. New road construction only has two purposes. First, to access new land uses, most usually residential (i.e. subdivisions) and/or second, to spur economic development in the form of commercial or industrial land uses (i.e. see numerous examples of ‘roads to nowhere’ that eventually string together an infection of suburban sprawl characterized by strip malls, office parks, and gated communities); and, both are founded on a single principle. The principle is: if you build it, they will come. This is the status quo. It has been the status quo in the United States for several decades. This brings us back to the message of the bumper sticker, i.e. “Paved roads: another fine example of unnecessary government spending.” It is message that insidiously favors the status quo for our contemporary models of urbanism. How has the status quo been working for our cities over the last half-century? The answer to that question should define your reaction the next time you come tail-to-front with this bumper sticker. Perhaps you will find the message as superficial as the vacant paradigm hiding behind it.

…Or, more accurately, we paid for it even if we did not need or want that road. New road construction only has two purposes. First, to access new land uses, most usually residential (i.e. subdivisions) and/or second, to spur economic development in the form of commercial or industrial land uses (i.e. see numerous examples of ‘roads to nowhere’ that eventually string together an infection of suburban sprawl characterized by strip malls, office parks, and gated communities); and, both are founded on a single principle. The principle is: if you build it, they will come. This is the status quo. It has been the status quo in the United States for several decades. This brings us back to the message of the bumper sticker, i.e. “Paved roads: another fine example of unnecessary government spending.” It is message that insidiously favors the status quo for our contemporary models of urbanism. How has the status quo been working for our cities over the last half-century? The answer to that question should define your reaction the next time you come tail-to-front with this bumper sticker. Perhaps you will find the message as superficial as the vacant paradigm hiding behind it.

What is this? A Department of Homeland Security/CIA intelligence gathering facility? A minimum security prison to house white-collar/Wall Street felons? No, it is worse. It is an elementary school in a Florida county! This is urban planning and design failing on an epic scale. 1) Built adjacent to a divided surface highway heavily used by semi-trucks. 2) Location? Wrong, wrong, wrong. 3) There are no sidewalks; 4) The school is not within walking distance of much of anything anyway so its urban functioning is completely dependent upon the automobile/school buses; 5) Two perimeter rings of fencing, one to keep the ‘bad people’ out and one to keep the children out of the retention ponds or wandering into the road; 6) When you see a public building with this much fencing, someone (i.e. the public officials) is really afraid of being sued for the most improbable of probabilities but only doing the minimum necessary in terms of cost (as opposed to building the school in the right location in the first place); 7) No visible windows; 8) I attended a high school that used the same plans for a prison in Indiana and this is much worse; and, 9) This is just one example of the mentality that builds schools throughout this county and many others in the State of Florida. However, the design of this school does multitask. It prepares our youngest generation for a future suburban life behind the walls of their gated communities… or their future life in prison. The mentality that builds schools like this one for our children is truly absurd and FUBAR.

Good theory leads to good planning and normative theory – without quantitative observation and validation using scientific method – is nothing more than subjective opinion masquerading as theoretical conjecture, says Mark David Major, senior planner in Nassau County, Florida, and former lecturer at The Bartlett School of Architecture and Planning, University College London.

VIEWPOINT

Holding up the bogeyman of the modernist architects of CIAM and their industrial age vernacular to deride scientific method and endorse normative theory in planning is a lot like suggesting a rape victim needs to date her attacker to get over the experience. While the metaphor may be shocking, it is not a casual choice.

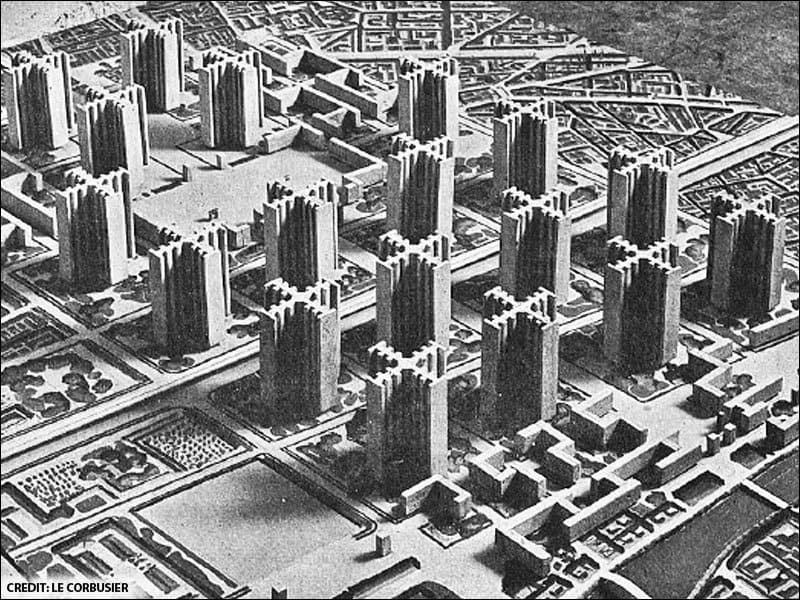

Modernism was a normative theory. It was a theory that aspired to science in its assertions. However, Modernist theory fails even the most basic tests of being science. It was long on observation and way short on testing the theoretical conjectures arising from those observations. Without scientific method to test its conjectures, Modernism in its infancy never made the leap from normative to analytical theory. Instead, the subjective opinions of the CIAM architects and planners were embraced by several generations of professionals and put into practice in hundreds of cities. Today, for the most part, Modernist theory has finally been tested to destruction by our real world experience of its effects. It has made the transformation from normative to analytical theory and validated as a failure.

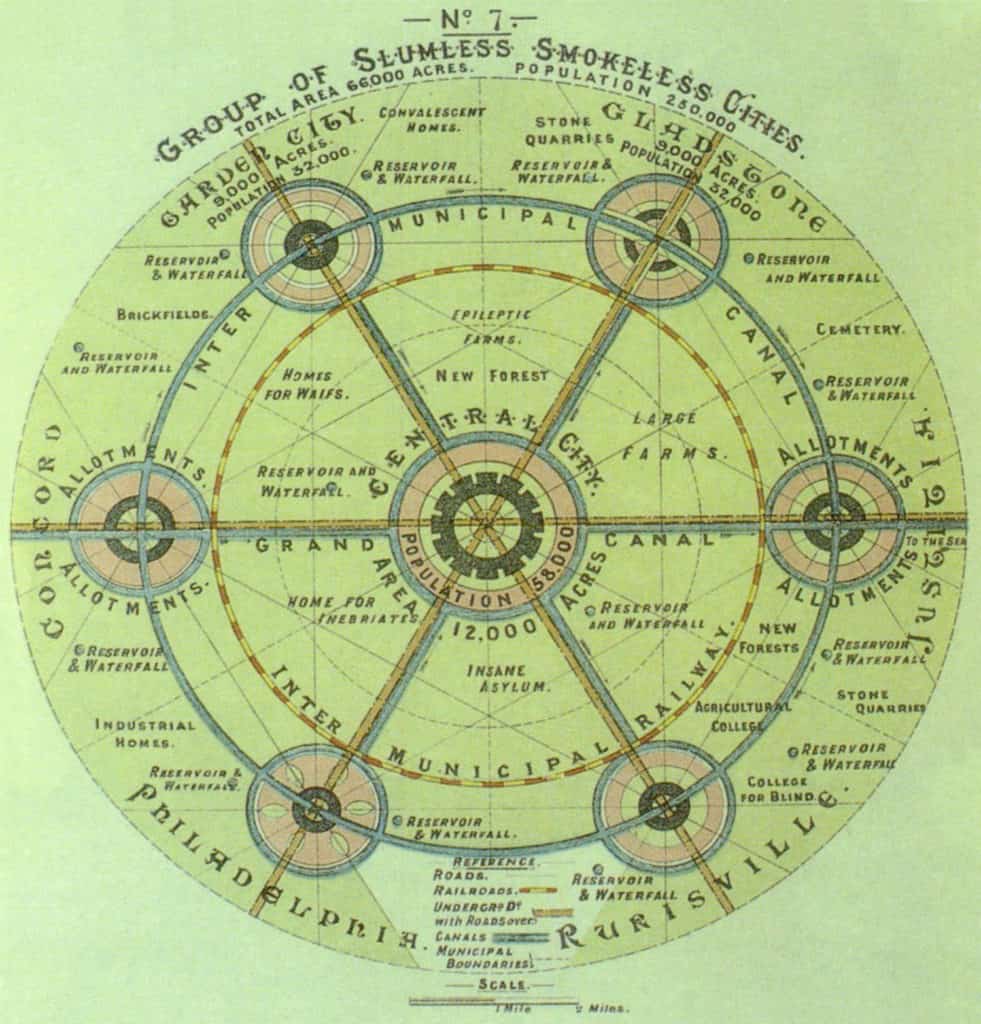

Modernism is the failure of normative theory. Ever since Robert Venturi published Learning from Las Vegas, it has been chic to assert that Modernism – and, by implication, science – was responsible for the rape of our cities in the 20th century. However, like a DNA test that frees a falsely accused rapist, scientific method reveals the true culprit – normative theory. The 20th century is a wasteland littered with the remnants of normative theories: modernism, futurism, Post-modernism, Deconstructivism, traditionalism, neo-sub urbanism and many more ‘-isms’. After the experience of the 20th century, it seems absurd to suggest  that we require more theoretical conjecture without scientific validation, more opinion and subjective observation – that is, less science – if we want to better understand the organized complexity of our cities.

that we require more theoretical conjecture without scientific validation, more opinion and subjective observation – that is, less science – if we want to better understand the organized complexity of our cities.

Science aspires to fact, not truth. The confusion about science is endemic to our society. You can witness it every time an atheist claims the non-existence of God based on scientific truth. However, science does not aspire to truth. Not only is ‘does God exist?’ unanswerable; it is a question no good scientist would ever seek to answer in scientific terms. It is a question of faith. The value judgment we place on scientific fact does not derive from science itself. It derives from the social, religious or cultural prism through which we view it. Right or wrong is the purview of politicians, philosophers and theologians. There are plenty – perhaps too many – planners and architects analogous to politicians, philosophers and theologians and not enough of the scientific variety. And, too often, those that aspire to science remain mired in the trap of normative theory.

The Modernist hangover lingers in our approach to theory. We require less subjective faith in our conjectures and more objective facts to test them. We persist with models that are colossal failures. When we are stuck in traffic, we feel like rats trapped in a maze. We apply the normative theory to how we model our transportation networks and fail to test the underlining conjecture. We project populations years and decades into the future, yet fail to return to them to test their validity, refine the statistical method and increase the accuracy of future projections. And we hide the scientific failings of our profession behind the mantra, ‘it’s the standard.’ The robust power of GIS to store and organize vast amounts of information into graphical databases is touted as transforming the planning profession. But those that don’t understand science, mistake a tool of scientific method for theory.

We require analytical theory and objective knowledge. If the facts do not support our conjectures, then they need to be discarded. In normative theory, ideas are precious. In analytical theory, they are disposable in favor of a better conjecture on the way to a scientific proof. Scientific method is the means to test and validate or dispose of theory. Our profession and communities have paid a terrible price for the deployment of Modernist theory in our cities. However, quantitative observation and analysis of its failings has offered enlightenment about how to proceed in the future. The work of notable researchers in Europe and the United States are leading the profession towards an analytical theory of the city. In the future, we will be able to deploy scientific method to derive better theory about the physical, social, economic and cultural attributes of the organized complexity of the city. The leap forward will propel planning out of the voodoo orbit of the social sciences and into the objective knowledge of true science. Until then, we need to focus a bit more on getting there and less time raising the specter of dead bogeymen in order to endorse the creation of a new one.

This editorial was written November 28, 2003 in response to a Viewpoint published in the December 2003 issue of the American Planning Association monthly, Planning, which derided science as a reasonable basis for sound planning and cited the experience of Modernism as a reason. This response was never published.