Review | Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies by Geoffrey West

Review | Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies by Geoffrey West

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist Contributor

West implicitly – and falsely – argues a city IS a tree; an idea that comes to us pre-refuted some 40 years courtesy of Christopher Alexander.

When I first heard about Geoffrey West’s Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies (Penguin Books, 2017) during Congress for New Urbanism 26 in Savannah, Georgia in May, I was eager to purchase a copy and begin reading the book. Once I started, each page that I read reminded me more and more of a conversation between John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) and Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) in Jurassic Park (1993):

HAMMOND: Codswollop, Ian. You’ve never been able to sufficiently explain your concerns.

MALCOLM: Oh, John, John, John (???). Because of the behavior of the system in phase space!

HAMMOND: A load, if I may say so, of fashionable number crunching!

However, as an audience, we side with Ian Malcolm in Jurassic Park because Jeff Goldblum is cool… and, well, dinosaurs are cool, too, except when they are eating you. However, being cool is not always a recipe for being right as anyone who attended high school can attest.

There are a lot of problems with West’s arguments and ideas in this book. This is not to say that there isn’t any potential value to be found in West’s Scale but you have to dig deep to find it; so deep that everyone should avoid the book except for only the most experienced and well-informed in the fields of biology, urban studies, and organizational research  I am not a biologist but I can see the potential value, as West argues, of establishing new medical baselines using scaling theory in the biological sciences. In the “Postscripts and Acknowledgements” at the end of the book, West admits these ideas have come under considerable criticism from people in the biological sciences. He dismisses this out-of-hand without actually mentioning or addressing what is the substance of these criticisms. I mention this because if West’s understanding of biological organisms is as naive as that of cities and companies, then the entire theoretical apparatus of Scale will collapse under the weight of West’s ambitions.

I am not a biologist but I can see the potential value, as West argues, of establishing new medical baselines using scaling theory in the biological sciences. In the “Postscripts and Acknowledgements” at the end of the book, West admits these ideas have come under considerable criticism from people in the biological sciences. He dismisses this out-of-hand without actually mentioning or addressing what is the substance of these criticisms. I mention this because if West’s understanding of biological organisms is as naive as that of cities and companies, then the entire theoretical apparatus of Scale will collapse under the weight of West’s ambitions.

I am an urban researcher so I am well-placed to discuss the many flaws of West’s approach to cities (and, to a lesser extent, companies, given my background in the private sector). Allow me to recount only a few of the most significant flaws in West’s book:

• West adopt an extremely narrow definition of science, which basically means no one is a scientist who is not a theoretical physicist. There are multiple generations of urban researchers performing quantitative data collection and analysis (not only qualitative research and surveys, as West asserts in the book) at and associated with institutions of higher learning at Cambridge University, University College London, MIT, University of California-Berkeley, and many others around the world who will take exception to this definition. West appears to do so in the interest of scientific rigor and, initially, I was willing to go along with him on this narrow definition. I’m all for scientific rigor and prefer on to err on the side of caution, i.e., if the R-squared of a correlation isn’t above .50, then I ignore it as meaningless. However, it soon becomes clear that West only adopts this narrow definition as a defense mechanism to guard his own ideas against criticisms, which can be easily dismissed with a ‘you’re not a real scientist’ retort.

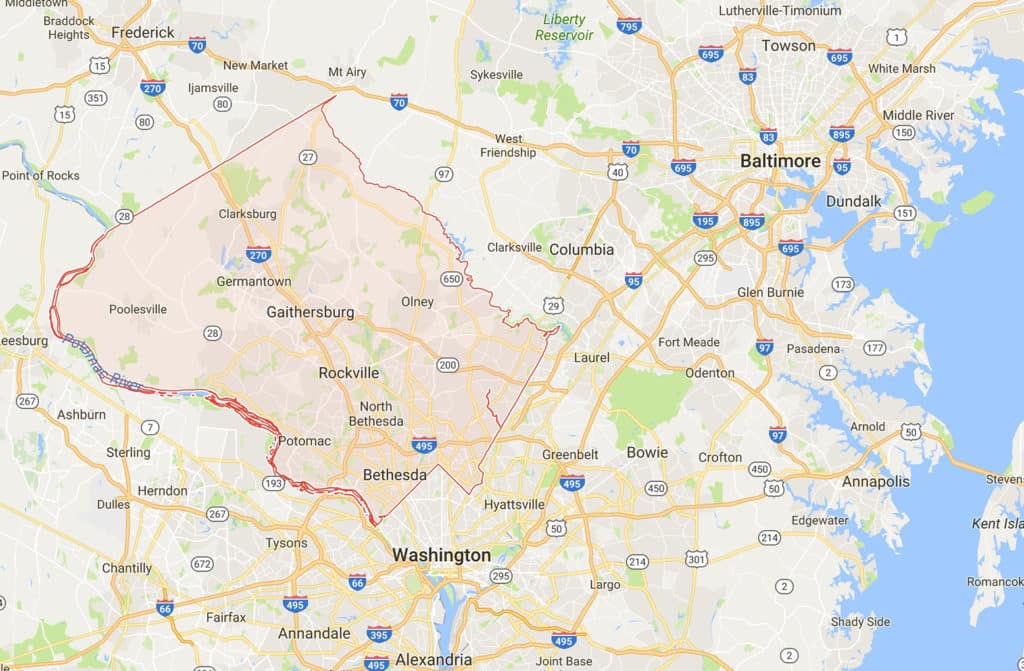

•  West presents some ideas as new that are only baked-over old ones; some very old. He asserts “cities are people” as if this is a new idea but West seems unaware that Spiro Kostof traced this paradigmatic approach to cities to Giovanni Botero in the early 17th century. Personally, I much prefer Jan Gehl’s approach that “cities are for people” but West seems unaware of the research of Gehl, William Whyte, and many others who have actually observed and quantified the human use of space in cities. In this, West also seems to have largely missed the point of Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities as he tends to exclusively focus on the economic aspects of her book. West only appears to stress the ‘cities are people’ approach so he can freely access available datasets, which have been collected (usually by public agencies) in a flawed manner. West briefly acknowledges the problems of boundary definition for such data collection in urban science. This is really problematic, especially for US census tracts. However, West then ignores the problem in his subsequent analyses. This is akin to an engineer saying “I can safely ignore gravity in my structural calculations because I have acknowledged its existence.”

West presents some ideas as new that are only baked-over old ones; some very old. He asserts “cities are people” as if this is a new idea but West seems unaware that Spiro Kostof traced this paradigmatic approach to cities to Giovanni Botero in the early 17th century. Personally, I much prefer Jan Gehl’s approach that “cities are for people” but West seems unaware of the research of Gehl, William Whyte, and many others who have actually observed and quantified the human use of space in cities. In this, West also seems to have largely missed the point of Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities as he tends to exclusively focus on the economic aspects of her book. West only appears to stress the ‘cities are people’ approach so he can freely access available datasets, which have been collected (usually by public agencies) in a flawed manner. West briefly acknowledges the problems of boundary definition for such data collection in urban science. This is really problematic, especially for US census tracts. However, West then ignores the problem in his subsequent analyses. This is akin to an engineer saying “I can safely ignore gravity in my structural calculations because I have acknowledged its existence.”

• In the same vein, West calls for a new science of cities based on network theory but he seems blissfully unaware of Bill Hillier and space syntax, which is an approach tying quantitative observation of the human use of space especially movement with mathematical modeling of spatial networks based on topological graph theory. Space syntax represents more than four decades of substantial urban research based on a scientific approach. West’s ignorance – unintentional or purposeful, I don’t know – about space syntax is especially troubling because he does cite and mention Carlo Ratti at MIT and Mike Batty at UCL. A cursory review of their bibliographies should have led West directly to Bill Hillier and space syntax. Apparently, West did not bother to conduct such a bibliography search. Instead, his knowledge of cities seems limited to what people who are actively collaborating with the Santa Fe Institute are willing to tell him. West also dismisses the work of Batty (and, by implication, everyone else in the Centre for Spatial Analysis at UCL) with a casual “I don’t agree.” I have known Mike Batty for twenty years so I can argue that he should wear West’s dismissal like a badge of honor. I don’t always agree with Professor Batty but he knows a lot more about cities than Geoffrey West. The fact is a science of cities have been developing for a half-century in the field of urban studies, more or less beginning with researchers like Leslie Martin, Lionel March, and Philip Steadman in the (now-named) Martin Centre of Architectural and Urban Studies at Cambridge University in the 1960s and 1970s. To make his arguments in Scale, West has to pretend that we are living circa 1965 and none of this research exists. In this, West comes across the quintessential Baby Boomer who starts on third base and thinks he hit a triple but also has to go back to first base because it is too inconvenient for his arguments to start on third.

• West’s book suffers from a peculiar phenomenon that I’ve observed over the years in American academia, especially in urban studies. West is Brit, who has spent most of his career in American academia. This is the phenomenon of ‘if it wasn’t thought of at an American university or research institute, then it doesn’t exist and/or count.”  There is something oddly arrogant about this phenomenon that I do not understand. I think it has something to do with first-world problems and being a member of the Top 1% of the world’s population. To be fair, the Congress for New Urbanism also seems to suffer from this particular problem (i.e., tunnel vision limited to the USA) even though it is primarily a professional organization. Someone should do some a research study.

There is something oddly arrogant about this phenomenon that I do not understand. I think it has something to do with first-world problems and being a member of the Top 1% of the world’s population. To be fair, the Congress for New Urbanism also seems to suffer from this particular problem (i.e., tunnel vision limited to the USA) even though it is primarily a professional organization. Someone should do some a research study.

• What is even more damning, given West’s bibliography on cities, is that it defies belief that he did not come across the work of Christopher Alexander and his associates at the University of California-Berkeley. West studiously avoids mentioning Alexander and the reasons will be obvious to most urban researchers. Manifestly, West’s ideas about cities are a biological analogy. It is in the title and again, an idea that has been around for a long time in architectural and urban studies. What this means is West’s ideas about cities come pre-refuted some 40 years earlier courtesy of Alexander’s most famous maxim: a city is not a tree. West has to avoid Alexander because his hierarchical network ideas implicitly – and falsely – argue the opposite. In this, West manages to misunderstand both cities and trees. Think of it this way: a heavy rain falls on a tree canopy and the water lands on one leaf on a higher branch but drips down from that leaf to another one on a lower branch crossing below. In West’s world, this cross-branching capability is irrelevant: trees are perfectly hierarchical systems without any overlap like the human circulatory system… as far as I’m aware capillaries do not cross-branch to share blood flow. This cross-branching capability is precisely what streets achieve in cities by connecting people and places. BTW, I might be open to the argument that a city is a scrub in terms of morphology though it is an analogy that strikes me – and probably many others – as insufficiently grandiose for the dynamic nature of cities.

• West also makes the classic sociologist’s mistake of thinking the only type of social interactions that matter is those involving some kind of high-level transaction.  However, most interaction in cities are low-level, non-verbal, and do not necessarily involve a measurable transaction (other than the measurement of co-presence itself) but only the potential for a transaction. Again, try thinking of it this way. It is commonly said that 80% of communication is body language so, in a city, the overwhelming majority of social interactions represent informational potentials: Scenario: “She’s pretty and l like the way she dresses, I wonder if I should trying chatting her up here on the street.” This is a non-verbal social interaction based on the potential of co-presence where the only transaction is information: what she looks like, what she is wearing, assessment of what you are wearing, what part of town are you in, what kind of people frequent that area, and so on. Option 1: You do talk to her, you date, get married, and have kids where there are now lots of measurable high-level transactions. Option 2: You chicken out, don’t talk to her and go home. There are no subsequent transactions unless you run into her again, i.e., the potential value of co-presence. West scaling theory views these potentials as irrelevant. They can be measured but West does not bother with quantitative observations. I would argue this is the very stuff of cities that makes them so dynamic and wonderfully fascinating as physical objects and, as West correctly argues, complex adaptive systems.

However, most interaction in cities are low-level, non-verbal, and do not necessarily involve a measurable transaction (other than the measurement of co-presence itself) but only the potential for a transaction. Again, try thinking of it this way. It is commonly said that 80% of communication is body language so, in a city, the overwhelming majority of social interactions represent informational potentials: Scenario: “She’s pretty and l like the way she dresses, I wonder if I should trying chatting her up here on the street.” This is a non-verbal social interaction based on the potential of co-presence where the only transaction is information: what she looks like, what she is wearing, assessment of what you are wearing, what part of town are you in, what kind of people frequent that area, and so on. Option 1: You do talk to her, you date, get married, and have kids where there are now lots of measurable high-level transactions. Option 2: You chicken out, don’t talk to her and go home. There are no subsequent transactions unless you run into her again, i.e., the potential value of co-presence. West scaling theory views these potentials as irrelevant. They can be measured but West does not bother with quantitative observations. I would argue this is the very stuff of cities that makes them so dynamic and wonderfully fascinating as physical objects and, as West correctly argues, complex adaptive systems.

• It is hard to believe that West’s Scale was properly refereed. A good referee would have advised him to cut the chapters on cities and companies to focus his arguments on biological systems, which seem stronger. West admits his knowledge of cities and companies is limited. He then spends almost 200 pages demonstrating how naive is his understanding of both. When it comes to organizational structures, it seems that West has never been involved in a small business venture nor oddly bothered to read Emile Durkheim, whose ideas on organic and mechanical solidarities would have been immensely valuable to better understand the social nature of companies.

• West admits his dataset on companies is biased toward publicly-traded companies on Wall Street. Yet he presents his findings as if they are universal to the organizational structure and life of all companies. If West had taken his findings of companies to their logical conclusion, then the bias of his data sample would have been apparent because the key takeaways would be: 1) emphasize short-term profit when young; and, 2) merge into oligarchic corporations with increased age. This is the data tail wagging the theoretical dog.

• In the same way, West does not take his biological analogy for cities to its logical conclusion either, This is because it would lead to the inevitable conclusion that the hierarchical manner in which we (especially in the USA) have been constructing suburban sprawl over the past half-century is the correct strategy, according to urban scaling theory. West does not mention it because he seems clearly aware that this would be an ill-advised conclusion given the advance of New Urbanism over the last three decades, which does get a brief mention. However, in even making this urban scaling theory argument about cities, West is assisting in perpetuating the dominant Modernist planning paradigm of the last century. This takes Scale into dangerously treacherous waters. Not mentioning it is not a strategy. It is avoiding the theoretical problems.

• In the same way, West does not take his biological analogy for cities to its logical conclusion either, This is because it would lead to the inevitable conclusion that the hierarchical manner in which we (especially in the USA) have been constructing suburban sprawl over the past half-century is the correct strategy, according to urban scaling theory. West does not mention it because he seems clearly aware that this would be an ill-advised conclusion given the advance of New Urbanism over the last three decades, which does get a brief mention. However, in even making this urban scaling theory argument about cities, West is assisting in perpetuating the dominant Modernist planning paradigm of the last century. This takes Scale into dangerously treacherous waters. Not mentioning it is not a strategy. It is avoiding the theoretical problems.

• Much of Scale comes across as cribbed from a series of TEDx lectures. There is nothing wrong with this approach as long as you are willing to do the work of editing the material into a coherent argument. Neither West nor the Penguin Books editors seemed willing to do so. West repeats the same argument with the exact same phrasing multiple things in the book, especially during its first half. I stopped counting after this occurred six times but it happens repeatedly and becomes increasingly irritating each instance.

• More than this, West is a mediocre writer. He continuously throws asides at the reader that come across as magician’s misdirection, i.e., look here while the trick goes on over there. He drops names, their CVs and awards, and grant funding like we are attending a Santa Fe cocktail party instead of reading a serious book. Too often, Scale comes across like West is trying to justify his tenure as the President of the Santa Fe Institute based on who he met instead of making a scientific argument based on what he knows. The overall effect comes across as arrogant, elitist and, in some instances, intellectually dishonest.

Proceed with caution and let the reader beware.

Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies

Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies

by Geoffrey West

Paperback, English, 496 pages

Penguin Press, 2017

ISBN-10: 1594205582

ISBN-13: 978-1594205583

You can purchase Scale by Geoffrey West on Amazon here.

Planning Naked | May 2017

Planning Naked | May 2017 Fight the power! Be a short-term rental outlaw! That statement is probably enough for me to be charged with inciting illegal activities in some jurisdictions.

Fight the power! Be a short-term rental outlaw! That statement is probably enough for me to be charged with inciting illegal activities in some jurisdictions.

Planning Naked | April 2017

Planning Naked | April 2017 Good News! You can be an Outlaw, too. The “New Hampshire Greenlights Granny Flats Statewide” article by Madeline Bodin (News Section, pp. 13) is great news! However, it is extremely disturbing that “the New Hampshire planning community was mixed on [the law].” Of course, the planners and municipalities initially opposing the law introduced a condition requiring that granny flats be ‘owner-occupied’, which is an insidious attempt to limit affordable, rental housing for lower income and young people. The Outlaw Urbanist would like to encourage all New Hampshire homeowners to violate this law immediately and continually since the ‘owner-occupied’ provision is essentially unenforceable. We are all outlaws now! “Lord I never drew first, But I drew first blood, I’m no one’s son, Call me young gun…”

Good News! You can be an Outlaw, too. The “New Hampshire Greenlights Granny Flats Statewide” article by Madeline Bodin (News Section, pp. 13) is great news! However, it is extremely disturbing that “the New Hampshire planning community was mixed on [the law].” Of course, the planners and municipalities initially opposing the law introduced a condition requiring that granny flats be ‘owner-occupied’, which is an insidious attempt to limit affordable, rental housing for lower income and young people. The Outlaw Urbanist would like to encourage all New Hampshire homeowners to violate this law immediately and continually since the ‘owner-occupied’ provision is essentially unenforceable. We are all outlaws now! “Lord I never drew first, But I drew first blood, I’m no one’s son, Call me young gun…”

Planning Naked | March 2017

Planning Naked | March 2017 Strike that. Reverse It. Welcome, Florida Lawyers Bearing Gifts. However, having said that, the more advanced state of staff reports in Florida – due to their quasi-judicial nature associated with the 1985 Growth Management Act and subsequently, Mr. Barnebey’s greater experience with the best of such staff reports – starkly contrasts with the next article, “The Better STAFF REPORT” by Bonnie J. Johnson (pp. 20-24). Allow me to state more simply the point that I believe Dr. Johnson is attempting to convey: the best staff reports combine: 1) well-written content with 2) well-designed visuals and 3) promptly get to the point. Like most planners, Dr. Johnson’s article manages to fail on all these counts. Johnson does not even seem to know her audience for this article (i.e. there are lots of different types of planners and staff reports) so she makes the mistake of trying to address ALL possible audiences. The result is inadequate for everyone. The graphic design of this article makes the content even more confusing. I mean it is really, really bad but hardly surprising. In my experience, most planners are woefully under-trained in the art of graphic design. I do not know if this is the fault of Dr. Johnson or Planning Magazine but, seriously, reading this article gave me a fucking headache.

Strike that. Reverse It. Welcome, Florida Lawyers Bearing Gifts. However, having said that, the more advanced state of staff reports in Florida – due to their quasi-judicial nature associated with the 1985 Growth Management Act and subsequently, Mr. Barnebey’s greater experience with the best of such staff reports – starkly contrasts with the next article, “The Better STAFF REPORT” by Bonnie J. Johnson (pp. 20-24). Allow me to state more simply the point that I believe Dr. Johnson is attempting to convey: the best staff reports combine: 1) well-written content with 2) well-designed visuals and 3) promptly get to the point. Like most planners, Dr. Johnson’s article manages to fail on all these counts. Johnson does not even seem to know her audience for this article (i.e. there are lots of different types of planners and staff reports) so she makes the mistake of trying to address ALL possible audiences. The result is inadequate for everyone. The graphic design of this article makes the content even more confusing. I mean it is really, really bad but hardly surprising. In my experience, most planners are woefully under-trained in the art of graphic design. I do not know if this is the fault of Dr. Johnson or Planning Magazine but, seriously, reading this article gave me a fucking headache.