A Compressed City of Time in Light | The City in Art

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

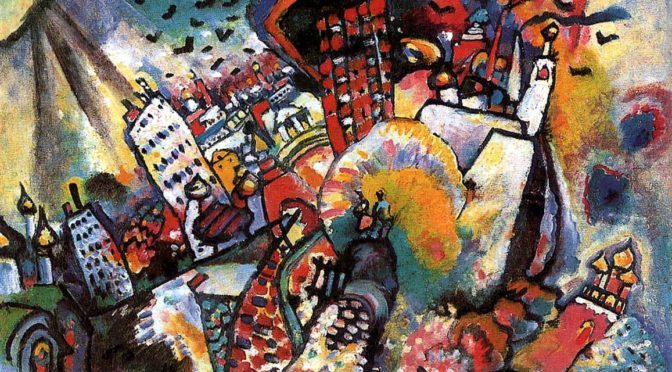

Wassily Kandinsky painted Moscow I in 1916 after he was forced to return to Russia in 1914 because of Germany’s declaration of war against Russia during World War I. The year 1915 was a period of profound depression and self-doubt during which he tried to build a new life at age 50 after living almost two decades in Munich, Germany. He did not paint a single picture. In 1916, Kandinsky painted Moscow I. He wrote, “I would love to paint a large landscape of Moscow — taking elements from everywhere and combining them into a single picture — weak and strong parts, mixing everything together in the same way as the world is mixed of different elements. It must be like an orchestra” (Becks-Malorny, Wassily Kandinsky, 1866–1944, 115).  Moscow I contains some of the same romantic fairy-tale qualities of his earlier paintings, fused with dramatic forms and colors. “The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot, which, like a wild tuba, sets all one’s soul vibrating” (Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” 360).

Moscow I contains some of the same romantic fairy-tale qualities of his earlier paintings, fused with dramatic forms and colors. “The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot, which, like a wild tuba, sets all one’s soul vibrating” (Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” 360).

At first glance, Kandinsky’s Moscow I appears to be a simple collage of landmarks, freed of the constraints of gravity and space, represented in a highly abstract manner by the artist. However, upon closer examination, there appears to be a logic to the almost spherical layout of objects composing the Moscow built environment (for example, the Kremlin is clearly represented towards the lower right). Using Kandisky’s own words about this painting as a guide (see above), we can hypothesize Kandisky placed these objects within the frame of the painting in relation to the time of day when each achieves its apex in terms of natural light and vibrant color, hence the almost spherical layout and luxurious richness of the hues. The spherical layout seems to mirror the path of the sun across the sky, or perhaps the daylight hours on the face of a clock. In this sense, Kandinsky’s Moscow I is a notional ‘clock of the city’, representing for us the optimal passage of time to see the collected objects of the city as shown in the painting. If true, then it is a clever means to elevate the painting beyond mere collage, above the mere randomness of collected objects that are compressed and freed of space. It also embeds his representation of Moscow with a kinetic energy that metaphorically accounts for the activity of urban life itself, the city as more than a mere collection of things but as a thing that, in itself, is alive.

About Wassily Kandinsky

About Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky (born December 16, 1866, died December 13, 1944) was a Russian painter and art theorist. He is credited with painting the first purely abstract works. With the possible exception of Marc Chagall (who was born/educated in Russia but adopted France as his home in adulthood to the point of being considered a “Russian-French” artist), Kandinsky is probably the most influential Russian artist in human history. Born in Moscow, Kandinsky spent his childhood in Odessa but later enrolled at the University of Moscow to study law and economics. Successful in his profession, he was offered a professorship (Chair of Roman Law) at the University of Dorpat where he began painting studies (life-drawing, sketching, and anatomy) at the age of 30. In 1896 Kandinsky settled in Munich, studying first at Anton Ažbe’s private school and then at the Academy of Fine Arts. He returned to Moscow in 1914 after the outbreak of World War I. Kandinsky was unsympathetic to the official theories on art in Communist Moscow and returned to Germany in 1921. There, he taught at the Bauhaus school of art and architecture from 1922 until the Nazis closed it in 1933. Like Chagall, he then moved to France where he lived for the rest of his life, becoming a French citizen in 1939, and producing some of his most prominent pieces of art. He died at Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1944. Unlike Chagall, Kandinsky never attained the status of being (in part) a French artist but has always been considered a definitive Russian one (Source: Wikipedia).

The City in Art is a series by The Outlaw Urbanist. The purpose is to present and discuss artistic depictions of the city that can help us, as professionals, learn to better see the city in ways that are invisible to others. Before the 20th century, most artistic representations of the city broadly fell into, more or less, three categories: literalism, pastoral romanticism, and impressionism, or some variation thereof. Generally, these artistic representations of the city lack a certain amount of substantive interest for the modern world. The City in Art series places particular emphasis on art and photography from the dawn of the 20th century to the present day.