“Can we move to Italy?

Meet me by the church up high on the hill.”

— Italy, Julia Fordham

Urban Patterns | Ragusa, Sicily, Italy

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

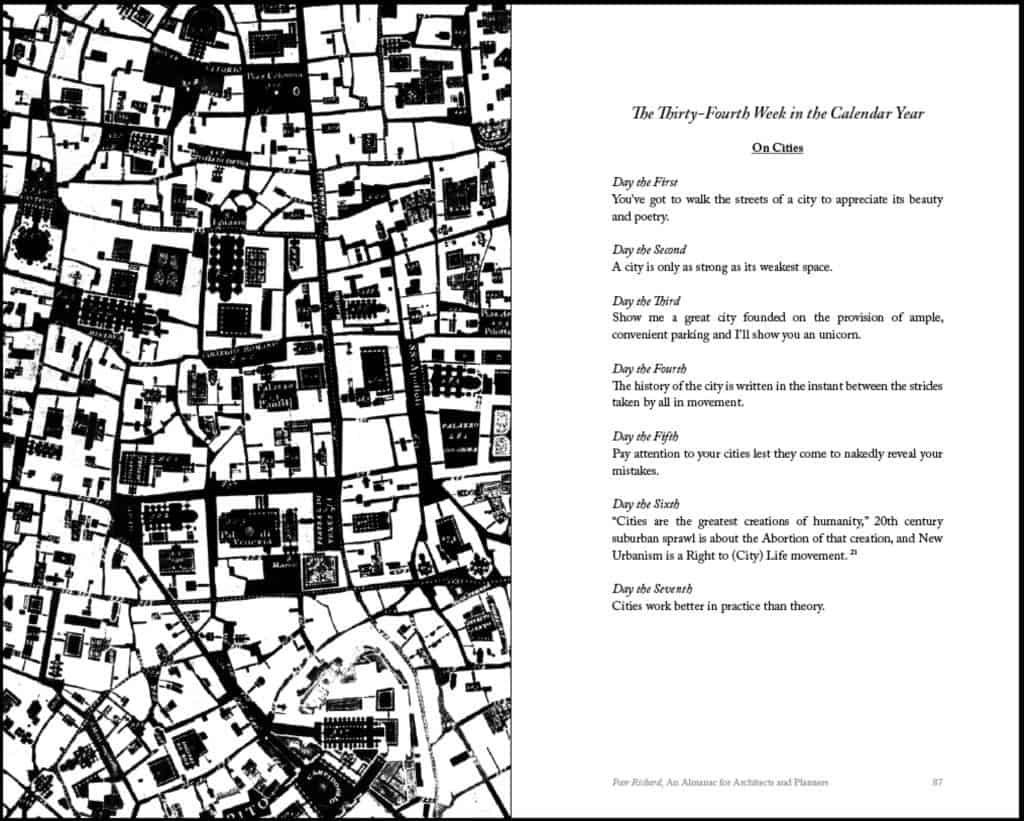

To many people, Ragusa, Sicily in Italy represents the prototypical Italian hilltop village lying below the Hyblaean Mountains. It is listed on the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The origins of the oldest part of the town on a 300-meter (980 feet) high hilltop (upper town to the right, below) lying between two valleys can be traced to the 2nd Millennium BC, i.e. more than 3,000 years ago. The ancient city came into contact with nearby Greek colonies and grew due to the nearby port of Camerina. Following a short period of Carthaginian rule, it fell into the hands of the ancient Romans and the Byzantines, who fortified the city and built a large castle. Ragusa was occupied by the Arabs in 848 AD, remaining under their rule until the 11th century, when the Normans conquered it. Thereafter Ragusa’s history followed the events of the Kingdom of Sicily, created in the first half of the twelfth century (Source: Wikipedia).

Upper town has a deformed grid layout where the street pattern conforms to the topography of the hill. This tends to make movement longer in terms of time and distance through upper town but changes in elevation are more gradual. This offers an excellent contrast to an urban pattern such as that found in San Francisco, where the regular grid layout enables movement through the layout to be shorter in terms of time and distance but changes in elevation tend to be much steeper. Together, Ragusa and San Francisco provide two models of how to incorporate acute topographical conditions within a settlement. The vertical construction of dwellings adapts to the topographical conditions of a local site in particular ways. In the case of San Francisco, this occurs by steeply adapting finished floors so they step up or down in section with the topography, which serves to maintain the conceptual logic of the regular grid imposed on the land. In Ragusa, the logic of the deformed grid in the town emerges from an apparently local process of aggregating dwelling units. During this aggregation process, finished floors are adapted to the contours of the topography so changes in finished floor elevation tend to be gradual instead of steep. In this way, the layout literally incorporates the acute topographical conditions into its functional pattern. This is why Moholy-Nagy (1968) describes such layouts as geomorphic. The street pattern of the newer areas adjacent to lower town (to the left, above) at the foot of the hill in the valley is a regular grid since the topography is less acute (e.g. more flat) at this location. The lower town also utilizes larger block sizes in its regular grid layout.

(Updated: April 11, 2017)

Urban Patterns is a series of posts from The Outlaw Urbanist presenting interesting examples of terrestrial patterns shaped by human intervention in the urban landscape over time.

Is there value in moisture retention for a road sign? Are the landscapers nurturing the ‘growth’ of this sign to a more adult height? Or perhaps additional moisture will enable the speed limit to grow above its current 15 MPH level? Is this what occurred with the overflow pipe? Was it originally only six inches in height and, over time, the additional moisture retention of mulching around the pipe enabled its growth an imposing height of two feet? Fire hydrants certainly require water in order to operate (upper right) but I’m pretty sure mulching has nothing to do with how they get water. Finally, why mulch around an electrical transformer (lower right)? It sits on a concrete pad, which is already well-hidden by the grass. Surely this was the point of painting them green in the first place, so they would be less noticeable. Personally, I didn’t even know they existed until they mulched around the base (read: sarcasm).

Is there value in moisture retention for a road sign? Are the landscapers nurturing the ‘growth’ of this sign to a more adult height? Or perhaps additional moisture will enable the speed limit to grow above its current 15 MPH level? Is this what occurred with the overflow pipe? Was it originally only six inches in height and, over time, the additional moisture retention of mulching around the pipe enabled its growth an imposing height of two feet? Fire hydrants certainly require water in order to operate (upper right) but I’m pretty sure mulching has nothing to do with how they get water. Finally, why mulch around an electrical transformer (lower right)? It sits on a concrete pad, which is already well-hidden by the grass. Surely this was the point of painting them green in the first place, so they would be less noticeable. Personally, I didn’t even know they existed until they mulched around the base (read: sarcasm).

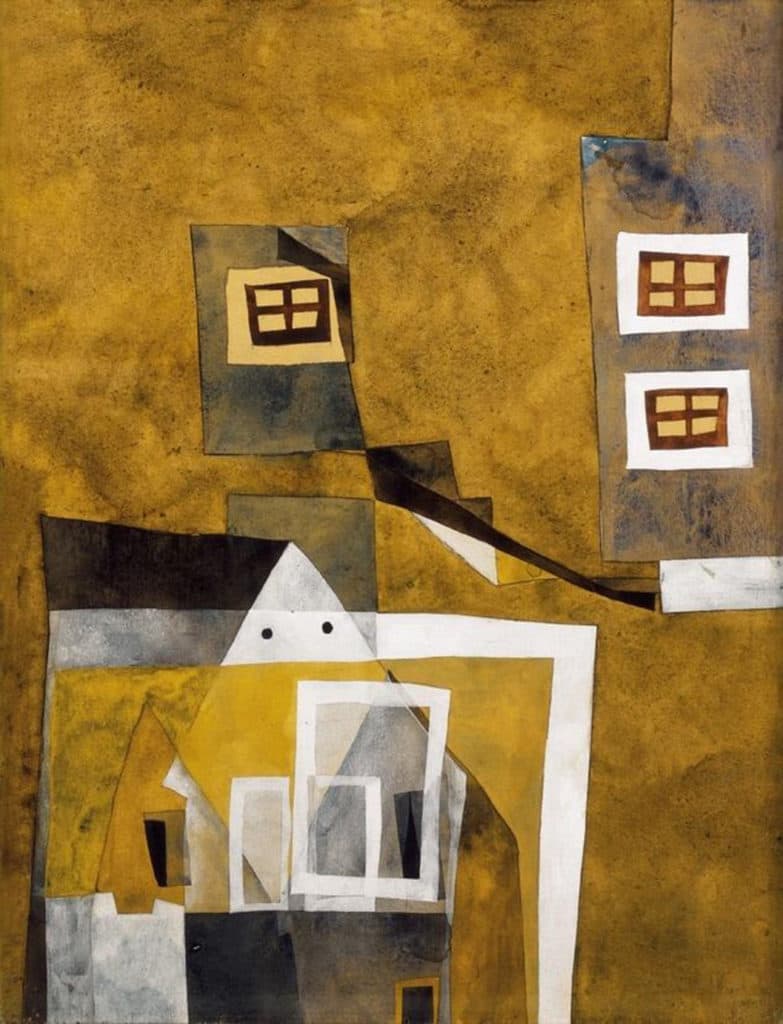

The intermittent use of white, providing a beautiful contrast to the predominant earth tones, appears principally reserved for representing man-made structural elements (window frames, a roof peak, and foundations). This embeds Floating Houses with a dialogue about the man-nature didactic. Interesting, the use of white (a symbol of purity) for representing these man-man structural components may suggest a positivist perspective on this subject within the composition.

The intermittent use of white, providing a beautiful contrast to the predominant earth tones, appears principally reserved for representing man-made structural elements (window frames, a roof peak, and foundations). This embeds Floating Houses with a dialogue about the man-nature didactic. Interesting, the use of white (a symbol of purity) for representing these man-man structural components may suggest a positivist perspective on this subject within the composition. About Lajos Vajda

About Lajos Vajda