Buildings in Motion | The City in Art

By Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

The city is always in motion. Generally, this statement is understood by professionals to refer to movement through urban space at street level (pedestrians, automobiles, and so forth) and/or the outward physical growth of the city in plan. However, the city is also – and always – in motion at its vertical dimension. It is not merely the movement of people and things vertically across interior elevations (such as elevators) but the buildings themselves move and, metaphorically speaking, grow. A structural engineer understands the need to account for wind shear in building structures, especially the taller the building. Anyone who has worked in and/or visited a skyscraper will have probably experienced the phenomenon of wind shear motion in that building, if only on a barely perceptible level. However, in a metaphorical sense, the buildings of the city are also ‘growing’ as new and higher buildings are erected over time. Harbert paints the buildings much like trees bending against a strong wind, providing a counter-motion horizontally, but also sprouting ever-upwards in a counter-motion against gravity associated with the plane of the ground. In The Blue City (2012), the ground plane is not represented by the solidity of terra firma but the fluidity of a nurturing water, which anchors the buildings much like water feeding the roots of trees. This gives the abstraction a dynamic and organic quality not normally associated with the vertical dimension of the city.

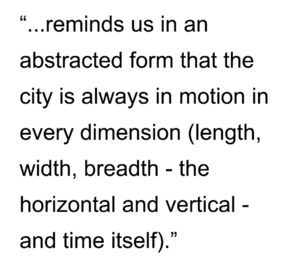

There is an eternal attribute about the city that Harbert captures in depicting a waterfront city at dusk. The onset of dusk is indicated both by the colors of the painting’s background and the use of white in representing the internal lights of the buildings, much in the same way as Georgia O’Keefe’s Radiator Building-Night, New York (1927). In The Blue City, the lights of the city buildings are abstractly reflected in the water at the base of the painting. There is a vibrancy of color contrasted between the upper (reds, browns, and greens) and lower portions (blues, whites, and greens) of the painting. The Blue City reminds us in an abstracted form that the city is always in motion in every dimension (length, width, breadth – the horizontal and vertical – and time itself). In this sense, Harbert captures something about the eternal dynamic of motion in the city. When it comes to the existential being of the city, we may not see it from afar – for example, as we gaze at the skyline of a city – but motion is an essential fact of the thing itself.

There is an eternal attribute about the city that Harbert captures in depicting a waterfront city at dusk. The onset of dusk is indicated both by the colors of the painting’s background and the use of white in representing the internal lights of the buildings, much in the same way as Georgia O’Keefe’s Radiator Building-Night, New York (1927). In The Blue City, the lights of the city buildings are abstractly reflected in the water at the base of the painting. There is a vibrancy of color contrasted between the upper (reds, browns, and greens) and lower portions (blues, whites, and greens) of the painting. The Blue City reminds us in an abstracted form that the city is always in motion in every dimension (length, width, breadth – the horizontal and vertical – and time itself). In this sense, Harbert captures something about the eternal dynamic of motion in the city. When it comes to the existential being of the city, we may not see it from afar – for example, as we gaze at the skyline of a city – but motion is an essential fact of the thing itself.

BIAS ALERT: I own this painting. I love it so much that I bought it for my private collection. Rejcel usually writes a short description of her paintings on www.rejcel.com but she has not done so for The Blue City. However, when I purchased the painting in 2012, I do recall her telling me the image for The Blue City came to her after a dream.

About Rejcel Harbert

About Rejcel Harbert

Rejcel Harbert has over eight years of experience as the owner of Art by Rejcel, where she sells photographic services, paintings, and abstract and expressionistic acrylic arts. She received her bachelor of arts in business, economics, and Spanish from Jacksonville University in 2001. She is a member of the Business Fraternity Alpha Kappa Psi, the Honor Society Phi Kappa Phi, and received an award from the Women’s Business Organization for Achievement. Ms. Harbert does religious volunteer work including construction and repair work for community members in need. For more information on Art by Rejcel, visit www.rejcel.com.

The City in Art is a series by The Outlaw Urbanist. The purpose is to present and discuss artistic depictions of the city that can help us, as professionals, learn to better see the city in ways that are invisible to others. Before the 20th century, most artistic representations of the city broadly fell into, more or less, three categories: literalism, pastoral romanticism, and impressionism, or some variation thereof. Generally, these artistic representations of the city lack a certain amount of substantive interest for the modern world. The City in Art series places particular emphasis on art and photography from the dawn of the 20th century to the present day.

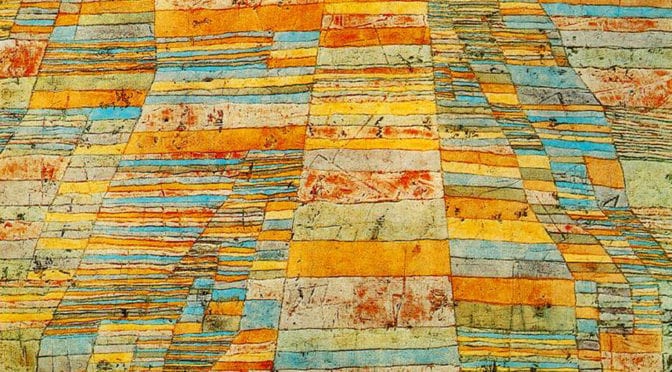

Perhaps skewed by an American perspective towards the land, it might suggest terre potentiel (the potential of the land). Humans have already intervened in the landscape for agricultural uses and the river already serves as a transportation hub, both associated with the support mechanisms for urban living. “In this pattern of fields, all is order, timeless structure, with a poetic element added… in twentieth-century creative language” (Source: PaulKlee.net). It is in this ‘timeless structure of order’ that can be found the design traces of a future urban pattern, a future city that has yet to emerge from the land but the potential for its emergence is already etched in the landscape. I love this painting, not so much for what it represents in the ‘here and now’ (though it is beautiful only on these terms) but what it represents about the possible, the “undiscovered country,” …the future, where all travelers must venture but none may journey before it is time.

Perhaps skewed by an American perspective towards the land, it might suggest terre potentiel (the potential of the land). Humans have already intervened in the landscape for agricultural uses and the river already serves as a transportation hub, both associated with the support mechanisms for urban living. “In this pattern of fields, all is order, timeless structure, with a poetic element added… in twentieth-century creative language” (Source: PaulKlee.net). It is in this ‘timeless structure of order’ that can be found the design traces of a future urban pattern, a future city that has yet to emerge from the land but the potential for its emergence is already etched in the landscape. I love this painting, not so much for what it represents in the ‘here and now’ (though it is beautiful only on these terms) but what it represents about the possible, the “undiscovered country,” …the future, where all travelers must venture but none may journey before it is time. About Paul Klee

About Paul Klee

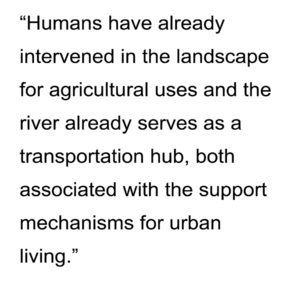

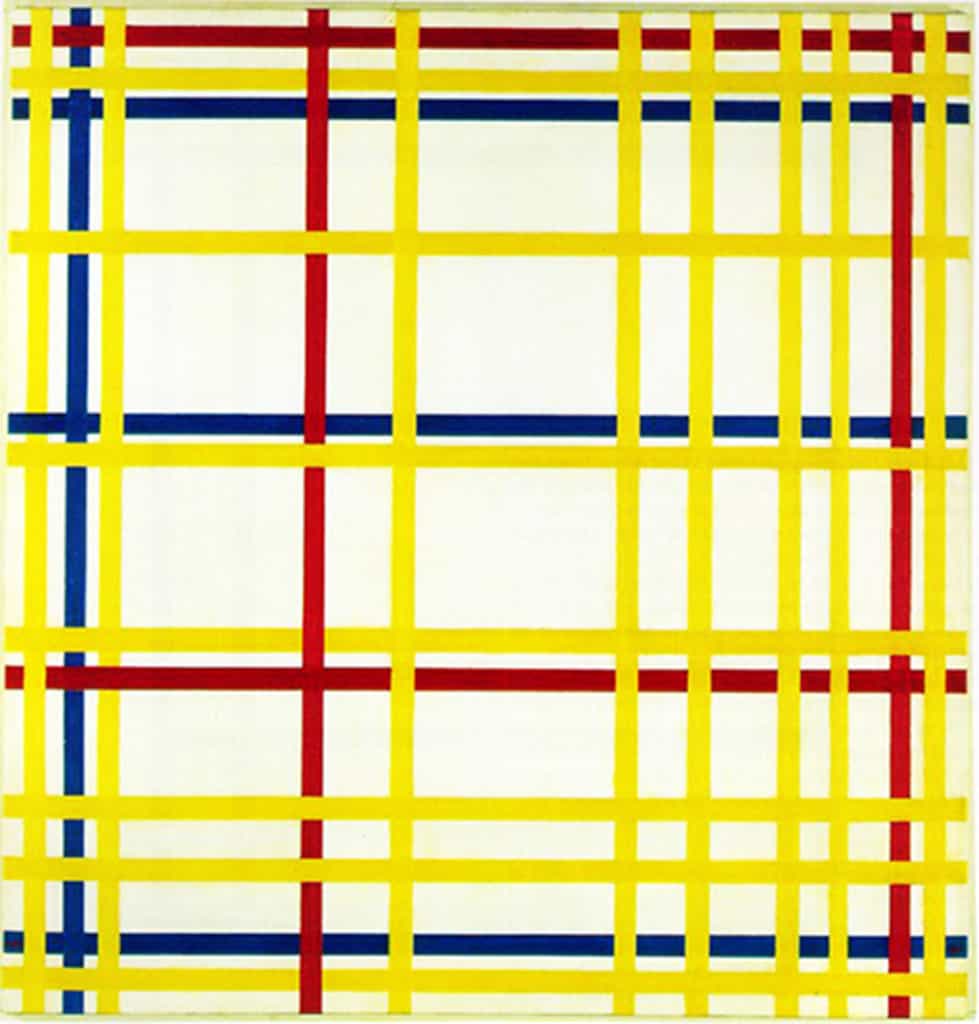

These white shapes could also be interpreted as ‘windows’ into those spaces. In this sense, Mondrian is playing with the two-dimensional plane of the canvas (a recurring motif of 20th-century representations of the city) to not only abstract but also ‘compress’ the abstraction of built space in the city. Given the De Stijl artists’ preference for universality in their abstractions, this latter interpretation might actually be closer to Mondrian’s original vision for the painting since the ‘vertical’ interpretation would be universal to all cities whereas the ‘horizontal’ one tends to be particular to New York and American cities in general. Mondrian’s New York City I builds upon and works within the artistic principles and framework outlined by Mondrian himself for the De Stijl movement, first reaching fruition in 1920 with Composition A: Composition with Black, Red, Gray, Yellow, and Blue. We will see some additional examples of Mondrian’s work in later issues of The City in Art.

These white shapes could also be interpreted as ‘windows’ into those spaces. In this sense, Mondrian is playing with the two-dimensional plane of the canvas (a recurring motif of 20th-century representations of the city) to not only abstract but also ‘compress’ the abstraction of built space in the city. Given the De Stijl artists’ preference for universality in their abstractions, this latter interpretation might actually be closer to Mondrian’s original vision for the painting since the ‘vertical’ interpretation would be universal to all cities whereas the ‘horizontal’ one tends to be particular to New York and American cities in general. Mondrian’s New York City I builds upon and works within the artistic principles and framework outlined by Mondrian himself for the De Stijl movement, first reaching fruition in 1920 with Composition A: Composition with Black, Red, Gray, Yellow, and Blue. We will see some additional examples of Mondrian’s work in later issues of The City in Art. About Piet Mondrian

About Piet Mondrian

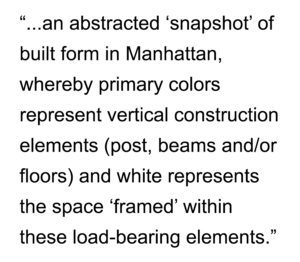

The intermittent use of white, providing a beautiful contrast to the predominant earth tones, appears principally reserved for representing man-made structural elements (window frames, a roof peak, and foundations). This embeds Floating Houses with a dialogue about the man-nature didactic. Interesting, the use of white (a symbol of purity) for representing these man-man structural components may suggest a positivist perspective on this subject within the composition.

The intermittent use of white, providing a beautiful contrast to the predominant earth tones, appears principally reserved for representing man-made structural elements (window frames, a roof peak, and foundations). This embeds Floating Houses with a dialogue about the man-nature didactic. Interesting, the use of white (a symbol of purity) for representing these man-man structural components may suggest a positivist perspective on this subject within the composition. About Lajos Vajda

About Lajos Vajda