BOOK REVIEW | Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism by Benjamin Ross

BOOK REVIEW | Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism by Benjamin Ross

Review by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

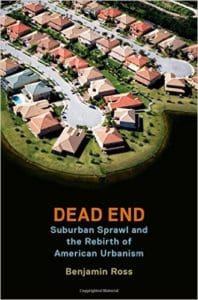

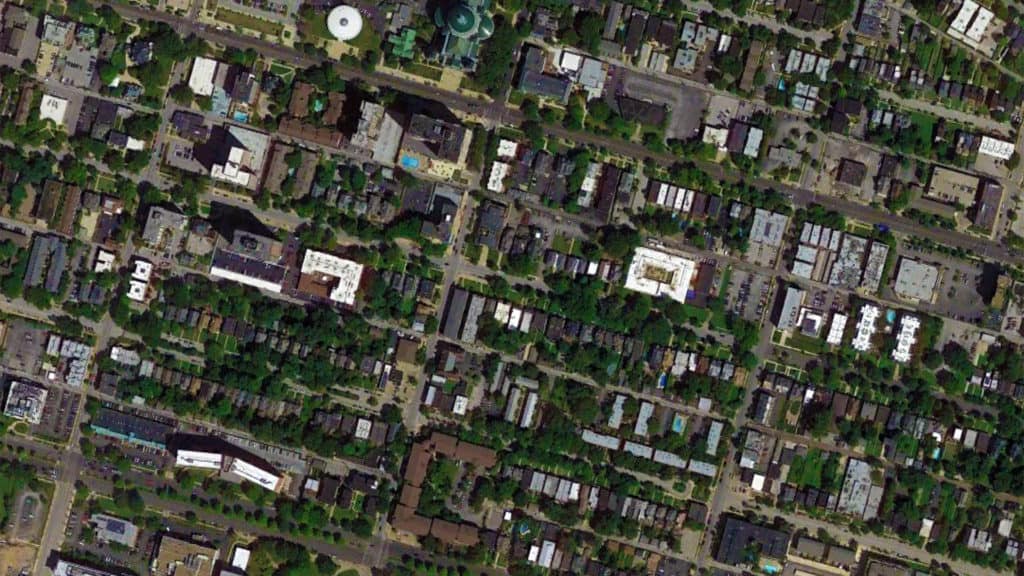

The first half of Benjamin Ross’ Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism (2014, Oxford University Press) is a majestic masterpiece of objective, clear, and concise diagnosis about the political, economic, and social origins of suburban sprawl in the United States with particular emphasis on the legal and regulatory pillars (restrictive covenants and exclusionary zoning ) perpetuating suburban sprawl to this day. It is required reading for anyone interested in the seemingly intractable problems of suburban sprawl we face today in building a more sustainable future for our cities. Chapters 1-10 (first 138 pages) of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism warrants a five-star plus rating alone.

However, Ross’ book becomes more problematic with the transition from diagnosis to prescription, beginning with an abrupt change in tone in Chapter 11. This chapter titled “Backlash from the Right” is, in particular, so politically strident that it reads as if the staff of Harry Reid’s Senate office wrote the text (the political left’s favorite boogeymen, the Koch Brothers, are even mentioned); or perhaps, the text of this chapter sprouted wholesale like Athena from the “vast right wing conspiracy” imaginings of Hillary Clinton’s head. This is unfortunate. In the second half of the book, Ross starts to squander most – if not all – of the trust he earned with readers during the exemplary first half of the book. It is doubly unfortunate because: first, it is done solely in the service of political dogma as Ross unconvincingly attempts to co-opt Smart Growth as a wedge issue for the political left in the United States; and second, it unnecessarily alienates ‘natural’ allies on the conservative and libertarian right sympathetic to Ross’ arguments for strong cities and good urbanism.

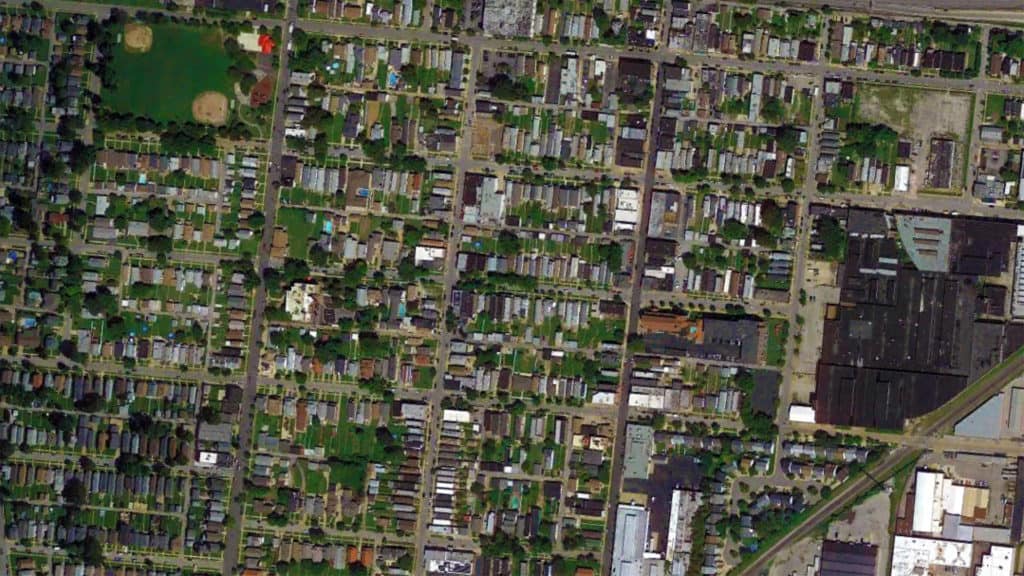

In the process, Ross tends to ignore or paper over blatant contradictions littering the philosophy of the political left in the United States when it comes to cities. Of course, this is a common Baby Boomer leftist tactic of absolving their generation for the collective disaster they’ve helped to create over the last half-century by confusing ideology for argument (and hoping no one will notice there’s a difference). For example, if you want to see what the policies of the political left look like after three-quarters of a century of dominance, then look no further than East St. Louis, Illinois. What has happened to that once vibrant city is absolutely criminal; literally so since several state and city Democratic officials and staffers have been sent to jail for corruption for decades.

During the second half of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, Ross also promotes the classic Smart Growth fallacy that public rail transit is the ‘magic bullet’ for reviving our cities. Indeed, public rail transit is important but too often Ross – like many others – comes across as unconsciously applying Harris and Ullman’s multi-nuclei model of city growth, which conveniently holds almost any function (in this case, rail stations/lines) can be randomly inserted almost anywhere in the fabric of a city without repercussions as long as land uses are ‘compatible.’ Of course, this is the ex post facto theoretical underpinning for the very ideas of Euclidean zoning and the common umbrella providing regulatory cover for all sorts of disastrous decisions in the name of “economic development.”

During the second half of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, Ross also promotes the classic Smart Growth fallacy that public rail transit is the ‘magic bullet’ for reviving our cities. Indeed, public rail transit is important but too often Ross – like many others – comes across as unconsciously applying Harris and Ullman’s multi-nuclei model of city growth, which conveniently holds almost any function (in this case, rail stations/lines) can be randomly inserted almost anywhere in the fabric of a city without repercussions as long as land uses are ‘compatible.’ Of course, this is the ex post facto theoretical underpinning for the very ideas of Euclidean zoning and the common umbrella providing regulatory cover for all sorts of disastrous decisions in the name of “economic development.”

This is a potentially dangerous self-delusion shared by many in the Smart Growth movement. For example, what Ross attributes as the cause for the failure of some rail stations (lack of walkable, urban development around these stations due to the over-provision of space for ‘park and ride’ lots in catering to the automobile) is often really a symptom. The real disease is these stations were put in the wrong location in the first place due to local opposition, regulatory convenience, and/or political cowardice (i.e. that’s where the land was available). There is an inherent danger in approaching pubic rail transit as a cure-all panacea for the city’s problems. If our leaders, planners, and engineers take shortcuts in the planning, design, and locating of rail lines/stations, then we leave the fate of our cities to happenstance. It is far too important of an issue to approach in such a cavalier manner, as some Smart Growth advocates appear so inclined.

In a general sense, this is not really different from the arguments made in Dead End but, specifically, it is an important distinction that is glossed over or not properly understood when drilling down into the crucial details of Ross’ prescriptions. That being said, there are some interesting tidbits and ideas in the ‘prescription phase’ of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism. However, the reader has to be extremely careful about filtering out Ross’ political agenda from the more important morsels. For example, Ross correctly points out Americans’ disdain for buses is rooted in social status. However, he fails to point out – or perhaps even realize – that this peculiar American attitude is indoctrinated from childhood due to the expansive busing of kids to school in the United States (e.g.. only the poor and unpopular kids take the bus). In order to change this attitude, you have to radically change public education policies, something contrary to the invested interests of the political left. In fact, Ross has very little to say about schools, which seems like an odd oversight.

Too often, Ross’s prescription for building coalitions comes across as the same, old political activism of the counter-culture Baby Boomers that doesn’t really rise above the level of gathering everyone around the campfire and singing “Kumbaya, My Lord” (absent the “My Lord” part in the interests of political correctness). In the end, this suggests Ross has a well-grounded understanding about the historical, political and social impact of legal and regulatory instruments at work in our cities (exemplified by the first half of this book) but only a superficial idea about the design and function of cities and movement networks (including streets and rail) as witnessed by the lackluster second half, which is barely worth a two-star rating. Because of these strengths and weaknesses, Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism is a four-star book in its entirety but you might be better served by reading the first half of the book, ignoring the second half, and having the courage to chart your own path in the fight for better cities.

Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism

Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism

by Benjamin Ross

Hardcover, English, 256 pages

New York: Oxford University Press (May 2, 2014)

ISBN-10: 0199360146

ISBN-13: 978-0199360147

Available for purchase from Amazon here.

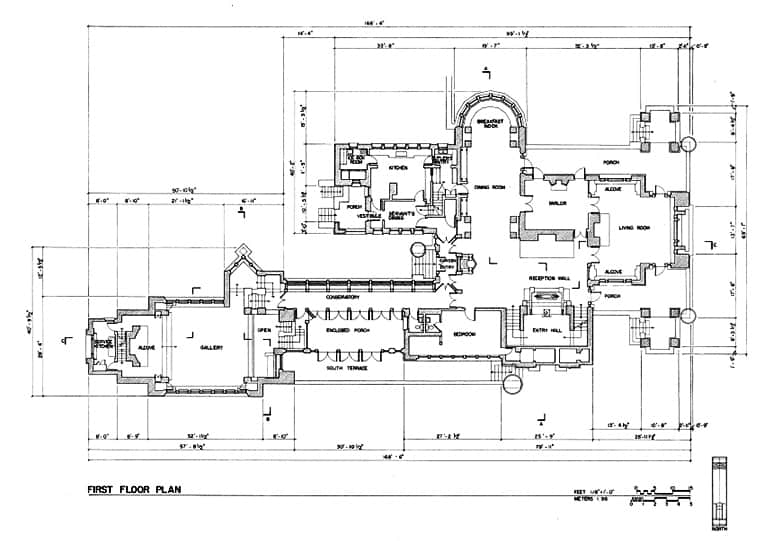

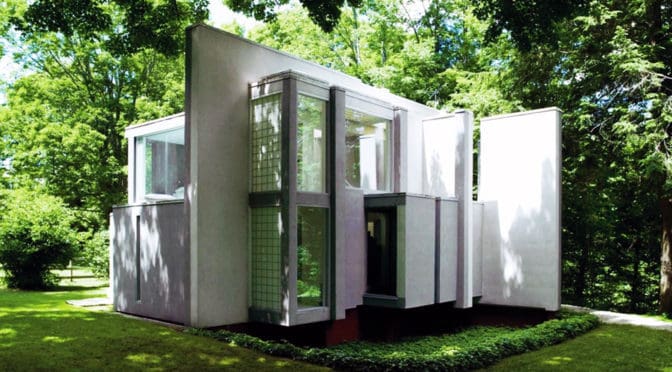

In particular, this includes the effect in structuring the relationships, if any, between public (e.g. everyday living) and private (e.g. bedrooms) functions as well as the household interface between inhabitants and visitors. The course offers a better understanding of the relationship between the architect’s stated aims in his own theoretical writings and the probable functioning of these houses as architectural objects (1.0 hour course).

In particular, this includes the effect in structuring the relationships, if any, between public (e.g. everyday living) and private (e.g. bedrooms) functions as well as the household interface between inhabitants and visitors. The course offers a better understanding of the relationship between the architect’s stated aims in his own theoretical writings and the probable functioning of these houses as architectural objects (1.0 hour course).

During the second half of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, Ross also promotes the classic Smart Growth fallacy that public rail transit is the ‘magic bullet’ for reviving our cities. Indeed, public rail transit is important but too often Ross – like many others – comes across as unconsciously applying Harris and Ullman’s multi-nuclei model of city growth, which conveniently holds almost any function (in this case, rail stations/lines) can be randomly inserted almost anywhere in the fabric of a city without repercussions as long as land uses are ‘compatible.’ Of course, this is the

During the second half of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, Ross also promotes the classic Smart Growth fallacy that public rail transit is the ‘magic bullet’ for reviving our cities. Indeed, public rail transit is important but too often Ross – like many others – comes across as unconsciously applying Harris and Ullman’s multi-nuclei model of city growth, which conveniently holds almost any function (in this case, rail stations/lines) can be randomly inserted almost anywhere in the fabric of a city without repercussions as long as land uses are ‘compatible.’ Of course, this is the