20 Must-Read Texts for Urban Planners (#1-10)

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Lists are often a handy tool to spark a discussion, debate, or even an argument. The purpose of this list is pretty straightforward, i.e. what should you have read. Of course, in limiting the list to a mere 20 texts (books and articles), there is no possible way it can be exhaustive. There are a lot of interesting texts out there from a lot of different perspectives (some better than others). It is also true that compiling such a list will inevitably reveal the particular biases of the person preparing the compilation (like revealing your iTunes playlist). In the end, it is only their opinion. There’s no way around it. This list demonstrates a clear bias towards texts about the relationship between the physical fabric of cities and their spatio-functional nature with a particular emphasis on first-hand observation of how things really work. Because of this, perhaps the most surprising thing about this list is how few texts there are by people who identify themselves as planners (or perhaps not, depending on your perspective). Finally, as with most lists, it is wise to reserve the right to amend/update said list in order to allow for any unfortunate oversights. Having said that, the list is an absolute good. The list is life. All around its margins lies suburban sprawl. Let the making of lists 1-10 begin…

10. “The Origin and Spread of the Grid-Pattern Town” (1946) by Dan Stanislawski

An old text, perhaps obscure to many and only familiar to a few, “The Origin and Spread of the Grid-Pattern Town” is one of the earliest and most thorough reviews of the evolution of regular grid town planning in the world. Yes, Stanislawski subscribes the spread of regular grid town planning to a process of historical diffusion, which Spiro Kostoff (see below) correctly points out nobody believes in any more. Despite this flaw, Stanislawski’s review is surprisingly comprehensive, for the most part. Stanislawski does seem to gloss over medieval town platting, see Maurice Beresford’s 1967 New Towns of the Middle Ages: Town Plantation in England, Wales and Gascony. However, some later writers ignore all together clear examples of regular grid planning in certain regions of the world (the Orient, for example). Stanislawski’s article is still a valuable resource today for any reader interested in the regular grid as long as they are careful about filtering out some of his misplaced – discredited today – ideas (for example, historical diffusion or the importance of Hippodamus).

The article is available here

9. “Savannah and the Issue of Precedent: City Plan as Resource” (1993) by Stanford Anderson

John Reps in his historical narrative of American town planning (see below) is enchanted with the historical ward plan of Savannah, as are many architects, urban designers, and planners. Reps is equally mystified (and a little despondent) about why the Savannah plan was not more influential in the history of American town planning. In “Savannah and the Issue of Precedent: City Plan as Resource,” Anderson offers a succinct and brilliant analysis about how the ward plan of Savannah operated in terms of street alignments and dwelling entrance locations working together to structure the outside-to-inside ‘assimilation’ of strangers into the town (principally in relation to the port). In generic terms, Savannah appears to be quite typical of a lot of waterfront settlements in American planning. However, its detailed specifications for squares and constitution are rigid, making it an inflexible model for early American town development (for example, compared to the flexibility of the Philadelphia or Spanish Laws of the Indies models). Anderson’s article should be on the standard reading list for any academic program in planning.

The article is available on Google Books here

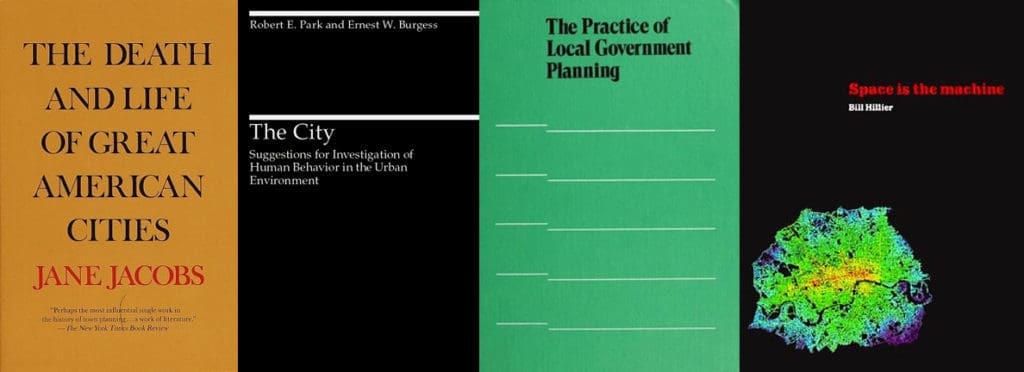

8. The Practice of Local Government Planning (2000)

It is one thing to complain about how planning works in the United States. However, it is hypocritical to complain without really understanding how planning works in the United States. The Practice of Local Government Planning offers a clear solution. For years, the various incarnations of the “green book” have been the go-to source for American planners to immerse themselves in the full scope of their profession in the United States. This Municipal Management Series book is the first one that any planner will open when seeking to pass the AICP exam. It is comprehensive and detailed. Warning: it is a very, very dry read. It is also extremely careful to remain neutral when presenting a picture about the way things work, i.e. this is what it is, not this is the right way to do things. In this sense, it is value-free and empty at its core. Nonetheless, it remains an invaluable resource for any planner, or anyone wanting to understand planners.

7. The City Assembled: The Elements of Urban Form Through History (1992) by Spiro Kostoff

6. The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History (1991) by Spiro Kostoff

5. Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning (1979) by John W. Reps

4. The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States (1965) by John W. Reps

Kostoff’s The City Shaped/The City Assembled are the crucial books about the history of town planning in the world for any urban planner to have on their bookshelves. Reps’ The Making of Urban America/Cities of the American West about the history of town planning in the United States are the crucial books for any urban planner to also have on their bookshelves. If an urban planner does not have these books on their bookshelves, it is reasonable to question the quality of said planner. There are other good historical narratives out there on the subject (Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s The Matrix of Man or Eisner and Gallion’s The Urban Pattern, for example). However, Kostoff and Reps’ books are the most comprehensive and thorough for their particular subjects. All four books incorporate hundreds of plans/plats and photographs to tell the story of town planning in the United States and world at large. They also offer detailed historical information (especially Reps) about the people and events involved in building our cities. Sometimes they are insightful and sometimes they are mistaken. For example, despite his protestations about the dichotomy so prevalent in town planning, Kostoff remains firmly entrapped within that dichotomy, i.e. ‘organic’ and ‘regular’ cities. Reps correctly points out the historical importance of William Penn’s plan of Philadelphia but misstates the reasons, assigning to Philadelphia what should have more appropriately been given to the Nine Square Plan of New Haven and the Spanish Law of the Indies, which Kostoff correctly emphasizes (though we are discussing subtle but important degrees of difference instead of a chasm in thought between both writers). When he ventures away from historical narrative and facts into the realm of opinion, Reps is often prone to undervalue the functional power of regular grid. However, these are endlessly useful texts for anyone interested in cities and the collection of plans and other historical documents (bird’s eye views) are a wonderful resource for any planner to have readily at hand.

3. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture (1996) by Bill Hillier

A purist could argue that anyone interested in space syntax should start with The Social Logic of Space (1984) by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson. The Social Logic of Space is an important book where Hillier and Hanson spell out a lot of groundwork for the theoretical and mathematical foundations of space syntax. However, they do so to a level of detail that some readers might find off-putting. Even Hillier and Hanson admit that one of its chapters is practically unreadable because it is so dry with technical detail. If you want to learn about the space syntax approach and some of its early, important findings without getting bogged down in the detail, then you will be better served by starting with Hillier’s Space is the Machine. Besides, Hillier is always careful about repeating the ‘big picture’ items that arose from The Social Logic of Space (beady ring settlements, restricted random process, and so on), so you won’t miss too much. For planners, the most important chapters in Space is the Machine to get immersed are about cities as movement economies, whether architecture can cause social malaise, and the fundamental city. There are plenty of goodies for architects as well. Space is the Machine is a must-read for anyone serious about a scientific approach to the built environment.

Space is the Machine is available here

2. The City: Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment (1925) by Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess

One of the planning profession’s biggest problems is that the Chicago School (the sociologists Park and Burgess and their colleague, Homer Hoyt, see sector model of city growth, who together were the founders of human ecology) got so much right from the very beginning that there wasn’t anywhere for planning to go from there but down. Of course, planning theory proceeded to accomplish this downhill spiral with great vigor and spectacularly bad results (see the second half of the 20th century). With the advent of the computer processor, Park and Burgess’ approach may appear somewhat quaint to modern eyes. However, the essentials about the city are there. More importantly, Park and Burgess never divorce the socio-economic nature of the city from its physical form but view them as intimately bound together. An important book and somewhat underrated in today’s world by planners, though it’s difficult to understand why or how that should be the case.

1. The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs

Big surprise, huh? These days it seems like anyone interested in cities is obsessed with Jane Jacobs, either in implementing and promoting her ideas or in feverishly going to ridiculous lengths trying to refute them (one might call it Jacobs Derangement Syndrome). Indeed, this obsession in itself is a testament to the power of her book. Ironically, for its time, the most novel thing Jacobs did was she dared to look out her window and observe how things were really working out there on the street. It’s a sad statement on the planning profession that this was somehow viewed as a sacrilege when the book was first published and, to a certain extent, this perception endures even today. I mean, how dare she actually suggest we evaluate (and, by implication, take responsibility for) the social and economic consequences of our planning decisions. The Death and Life of Great American Cities is the essential book for any planner.

The circus of Senate confirmation hearings for the Secretary of Cities, brought to you by National Ready Mixed Concrete Association and Community Organizations International, just as soon as the Senator from Montana releases his hold on the nomination! Stay tuned! More pigs feeding at the Federal trough would inevitably populate Florida’s Department of Cities. That is fine for the pigs but what about the rest of us?

The circus of Senate confirmation hearings for the Secretary of Cities, brought to you by National Ready Mixed Concrete Association and Community Organizations International, just as soon as the Senator from Montana releases his hold on the nomination! Stay tuned! More pigs feeding at the Federal trough would inevitably populate Florida’s Department of Cities. That is fine for the pigs but what about the rest of us? The only way a Federal Department of Cities could alter the prevailing development paradigm in this country for the last century is if we are willing to place Smart Growth for our cities at the top of the agenda by subsuming the Department of Transportation, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Environmental Protection Agency, and other disparate Federal agencies and offices (Office of Urban Affairs, and so on) under one roof. Incidentally, this is probably the only way a new Department of Cities could generate bipartisan support by allowing the left and the right to explicitly address their key constituencies (urban interests on one hand, reducing and streamlining government on the other). It would also require both parties adopting an united front to take on other special interests threatened by such reform (most obviously, radical environmentalists). In the absence of such radical thinking, our cities are safer as “laboratories for pragmatic bipartisan policy innovation, pioneering new approaches on everything from schools, crime and gun control to economic development” at the local and State level.

The only way a Federal Department of Cities could alter the prevailing development paradigm in this country for the last century is if we are willing to place Smart Growth for our cities at the top of the agenda by subsuming the Department of Transportation, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Environmental Protection Agency, and other disparate Federal agencies and offices (Office of Urban Affairs, and so on) under one roof. Incidentally, this is probably the only way a new Department of Cities could generate bipartisan support by allowing the left and the right to explicitly address their key constituencies (urban interests on one hand, reducing and streamlining government on the other). It would also require both parties adopting an united front to take on other special interests threatened by such reform (most obviously, radical environmentalists). In the absence of such radical thinking, our cities are safer as “laboratories for pragmatic bipartisan policy innovation, pioneering new approaches on everything from schools, crime and gun control to economic development” at the local and State level. Why would we expect our citizens (and their representatives) to ever trust us and put us in charge when we have demonstratively failed our cities time and time again during their lifetime, their parents’ lifetime, and their grandparents’ lifetime? Instead of searching for magic bullets (like Florida’s idea), let us dedicate ourselves to leading for our cities. The irony is, if we truly did this, we would probably find the perceived need for Florida’s proposal and others like them would disappear. Unless, of course, the point is to become one of the fattest pigs at the trough. If this is the case, then never mind…

Why would we expect our citizens (and their representatives) to ever trust us and put us in charge when we have demonstratively failed our cities time and time again during their lifetime, their parents’ lifetime, and their grandparents’ lifetime? Instead of searching for magic bullets (like Florida’s idea), let us dedicate ourselves to leading for our cities. The irony is, if we truly did this, we would probably find the perceived need for Florida’s proposal and others like them would disappear. Unless, of course, the point is to become one of the fattest pigs at the trough. If this is the case, then never mind…