Pruitt-Igoe | A Photographic Essay

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

Today, we set a very specific task to promote our forthcoming, new course on The Outlaw Urbanist online learning platform: “A Failure of Modernism: ‘Excavating’ Pruitt-Igoe” (2.0 hour). Namely, create a photographic essay telling the story, in part, of the Pruitt-Igoe Public Housing Complex in St. Louis, Missouri using only ten photographs with shortish captions, i.e. no plans, maps, statistics, or computer models. Quite frankly, it is a near impossible task. Nonetheless, the photos are fascinating and there are plenty of informative links to related materials available in the captions so you can discover more about this (in)famous housing project.

Pruitt-Igoe is one of the most commonly cited examples of the failure of Modernism in the world. The televised demolition of Pruitt-Igoe residential towers in 1972 is one of the most iconic images of 20th-century architecture and planning (Photograph: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth Press Materials).

Pruitt-Igoe is one of the most commonly cited examples of the failure of Modernism in the world. The televised demolition of Pruitt-Igoe residential towers in 1972 is one of the most iconic images of 20th-century architecture and planning (Photograph: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth Press Materials).

Opening circa 1954, Pruitt-Igoe was Federally-funded social housing constructed with 2,870 apartments for 13,000 people (228 people/acre) in thirty-three 11-story buildings on 57 acres with a housing density of 50 dwelling units per acre in north St. Louis (Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis via The Guardian).

Opening circa 1954, Pruitt-Igoe was Federally-funded social housing constructed with 2,870 apartments for 13,000 people (228 people/acre) in thirty-three 11-story buildings on 57 acres with a housing density of 50 dwelling units per acre in north St. Louis (Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis via The Guardian).

Pruitt-Igoe was a ‘hybrid design’ for a high-profile, strategic site. It incorporated Modernist principles (i.e. high-rises towers, separation of uses and building siting, stripped down aesthetics where ‘form follows function, etc.) utilizing a regular grid layout in the urban pattern of St. Louis, which was commonly planned on offsetting ‘smallish’ regular grids in a process of deformation, i.e. small for American cities, big for European ones (Photograph: U.S. Geological Survey via Wikipedia Commons).

Pruitt-Igoe was a ‘hybrid design’ for a high-profile, strategic site. It incorporated Modernist principles (i.e. high-rises towers, separation of uses and building siting, stripped down aesthetics where ‘form follows function, etc.) utilizing a regular grid layout in the urban pattern of St. Louis, which was commonly planned on offsetting ‘smallish’ regular grids in a process of deformation, i.e. small for American cities, big for European ones (Photograph: U.S. Geological Survey via Wikipedia Commons).

Pruitt-Igoe replaced 19th-century tenement housing, which was typical of the DeSoto-Carr neighborhood and many areas of St. Louis at the time. Survey of a 1938 Sanborn map indicates there were a minimum of 730 street-oriented dwelling entrances with minimal street setbacks on the site before Pruitt-Igoe, i.e. exclusive of buildings with deep setbacks, large (non-residential) footprints, alleyway-access, and vacant lots (Photograph: State Historical Society and Missouri/University of Missouri-St. Louis Archives).

Pruitt-Igoe replaced 19th-century tenement housing, which was typical of the DeSoto-Carr neighborhood and many areas of St. Louis at the time. Survey of a 1938 Sanborn map indicates there were a minimum of 730 street-oriented dwelling entrances with minimal street setbacks on the site before Pruitt-Igoe, i.e. exclusive of buildings with deep setbacks, large (non-residential) footprints, alleyway-access, and vacant lots (Photograph: State Historical Society and Missouri/University of Missouri-St. Louis Archives).

The pilotis design feature partially ‘liberated’ the ground level for circulation routes, which crucially mediated inside to outside and vice versa, i.e. formal access to the elevator/stairwells in each tower and spatial distribution in the exterior spaces of the layout. The residential towers elevated dwelling entrances in section to internal corridors, effectively representing a complete elimination of front doors in the site (Photograph: Affordable Housing Institute).

The pilotis design feature partially ‘liberated’ the ground level for circulation routes, which crucially mediated inside to outside and vice versa, i.e. formal access to the elevator/stairwells in each tower and spatial distribution in the exterior spaces of the layout. The residential towers elevated dwelling entrances in section to internal corridors, effectively representing a complete elimination of front doors in the site (Photograph: Affordable Housing Institute).

The cost-cutting inclusion of ‘skip-stop’ elevators only stopping at the 1st, 4th, 7th, and 10th floors forced most residents to use dark stairwells – principally designed as fire exits – to access the floors of their apartment. They were publicly accessible due to the uncontrolled pilotis design feature, which also provided access to multiple routes at ground level in an ‘easy to read and use’ layout. Collectively, this facilitated opportunity and escape for criminal activities, initially focused on the stairwells but later spreading to other spaces (Photograph: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth).

The cost-cutting inclusion of ‘skip-stop’ elevators only stopping at the 1st, 4th, 7th, and 10th floors forced most residents to use dark stairwells – principally designed as fire exits – to access the floors of their apartment. They were publicly accessible due to the uncontrolled pilotis design feature, which also provided access to multiple routes at ground level in an ‘easy to read and use’ layout. Collectively, this facilitated opportunity and escape for criminal activities, initially focused on the stairwells but later spreading to other spaces (Photograph: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth).

People must have quickly realized the opportunities inherent in the design and planning of the pilotis feature because intensive patrols of the buildings and grounds began shortly after Pruitt-Igoe opened, even before any welfare recipients were allowed to live there. Former residents indicate these stairwells/elevators were problematic spaces from the very beginning (Photograph: St. Louis Post-Dispatch).

People must have quickly realized the opportunities inherent in the design and planning of the pilotis feature because intensive patrols of the buildings and grounds began shortly after Pruitt-Igoe opened, even before any welfare recipients were allowed to live there. Former residents indicate these stairwells/elevators were problematic spaces from the very beginning (Photograph: St. Louis Post-Dispatch).

The number of unsupervised children in archival footage of Pruitt-Igoe is startling. ‘Baked-in’ problems of racism accentuated by many regulatory failures skewed Pruitt-Igoe’s demographics towards female-led households with children. Declining occupancy led to a ‘broken interface’ between adults and children. There were too few adults (especially males who belonged there) and too many children for too much space. Unsupervised children (especially teenagers) participated in petty vandalism, which worsened the perception of social malaise at Pruitt-Igoe (Photograph: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth).

The number of unsupervised children in archival footage of Pruitt-Igoe is startling. ‘Baked-in’ problems of racism accentuated by many regulatory failures skewed Pruitt-Igoe’s demographics towards female-led households with children. Declining occupancy led to a ‘broken interface’ between adults and children. There were too few adults (especially males who belonged there) and too many children for too much space. Unsupervised children (especially teenagers) participated in petty vandalism, which worsened the perception of social malaise at Pruitt-Igoe (Photograph: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth).

There was an asymmetrical relationship (i.e. unequal) between the Vaughan (foreground) and Pruitt-Igoe (background) social housing in terms of formal access, horizontal and vertical scale, and spatial distribution. Nine strategic diagonal/gridline routes passing through, within or to the edge of Vaughan provided direct/adjacent access to every Pruitt-Igoe residential tower, suggesting the opening of Vaughan circa 1957-58 might have been complicit in Pruitt-Igoe’s social malaise (Photograph: U.S. Geological Survey).

There was an asymmetrical relationship (i.e. unequal) between the Vaughan (foreground) and Pruitt-Igoe (background) social housing in terms of formal access, horizontal and vertical scale, and spatial distribution. Nine strategic diagonal/gridline routes passing through, within or to the edge of Vaughan provided direct/adjacent access to every Pruitt-Igoe residential tower, suggesting the opening of Vaughan circa 1957-58 might have been complicit in Pruitt-Igoe’s social malaise (Photograph: U.S. Geological Survey).

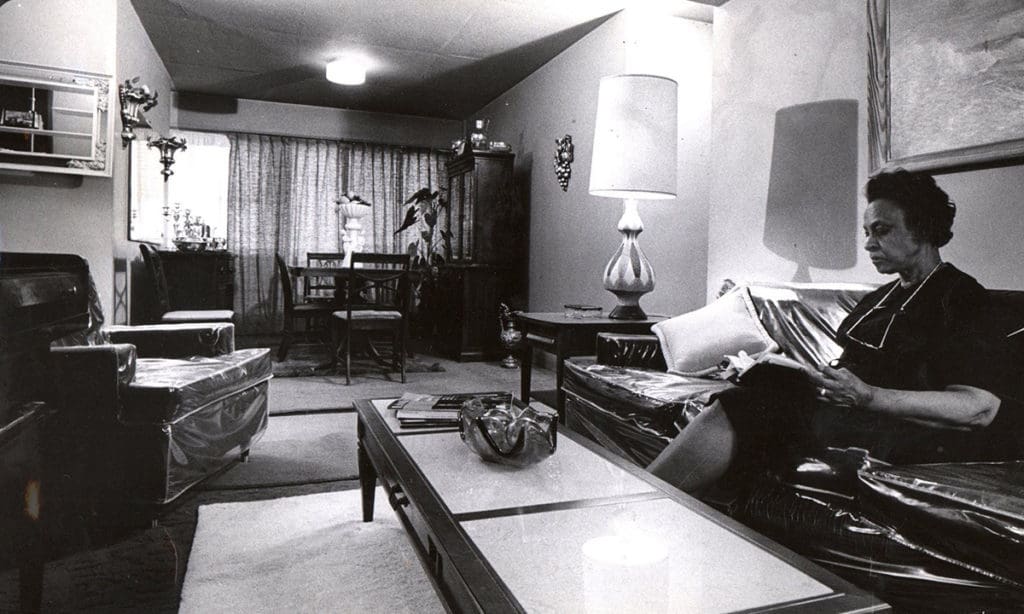

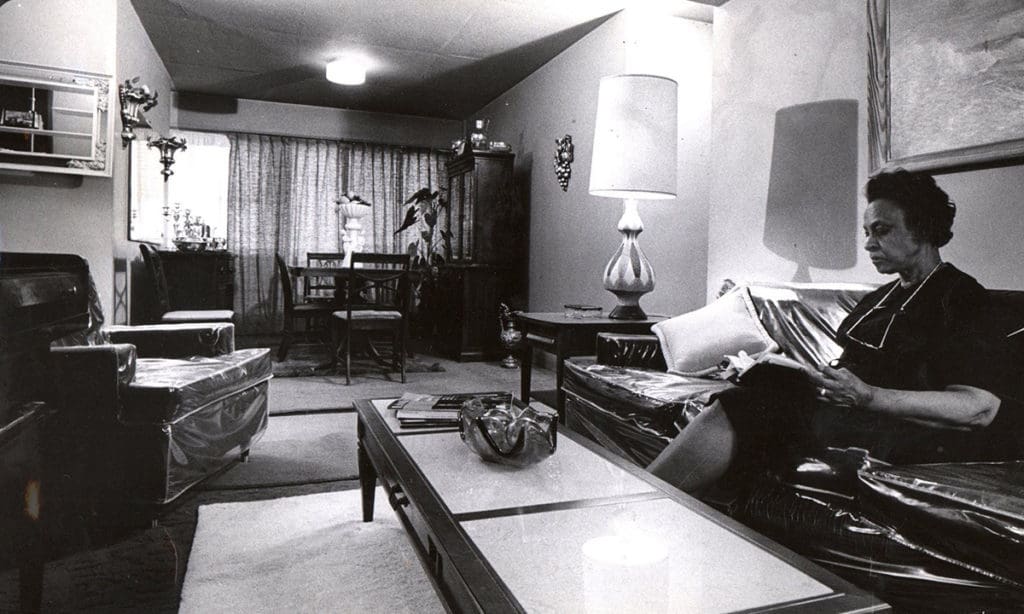

Social malaise accelerated at Pruitt-Igoe during the 1960s even as residents maintained some apartment interiors until a cataclysmic mechanical failure in 1968 (watch a 5-minute KMOX news report on YouTube here) led to a St. Louis Public Housing Authority order for phrased vacating of the premises in preparation for demolition. According to news reports/resident testimony, the worst, most violent criminal activities at Pruitt-Igoe occurred during this 5-year period from 1968-1972 (Photograph: Zuma Press/Alamy via The Guardian).

Social malaise accelerated at Pruitt-Igoe during the 1960s even as residents maintained some apartment interiors until a cataclysmic mechanical failure in 1968 (watch a 5-minute KMOX news report on YouTube here) led to a St. Louis Public Housing Authority order for phrased vacating of the premises in preparation for demolition. According to news reports/resident testimony, the worst, most violent criminal activities at Pruitt-Igoe occurred during this 5-year period from 1968-1972 (Photograph: Zuma Press/Alamy via The Guardian).

This photographic essay only begins to scratch the surface of the issues surrounding this housing project. There is MUCH MORE to the story of Pruitt-Igoe. Learn more by participating in our forthcoming, new course — “A Failure of Modernism: ‘Excavating’ Pruitt-Igoe” — when it becomes available!

Our purpose is to better understand how design and planning contributed to its social malaise. It concludes: 1) provision of space (i.e. quantity) became a liability as declining occupancy generated a ‘broken interface’ between adults and children; and, 2) the pilotis of the residential towers mediated formal access and spatial distribution in a layout characterized by ‘intelligible dysfunction,’ which facilitated opportunity and escape for criminal activities. Both fed the perception and reality of social malaise at Pruitt-Igoe (2.5 hour course). Click here to purchase this course ($17.49).

Our purpose is to better understand how design and planning contributed to its social malaise. It concludes: 1) provision of space (i.e. quantity) became a liability as declining occupancy generated a ‘broken interface’ between adults and children; and, 2) the pilotis of the residential towers mediated formal access and spatial distribution in a layout characterized by ‘intelligible dysfunction,’ which facilitated opportunity and escape for criminal activities. Both fed the perception and reality of social malaise at Pruitt-Igoe (2.5 hour course). Click here to purchase this course ($17.49). Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A is an architect and planner with extensive experience in urban planning and design, business management and real estate development, and academia. He is a Professor of Urban Design at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Mark has been a visiting lecturer at the University of Florida, Georgia Tech, Architectural Association in London, the University of São Paulo in Brazil, and Politecnico di Milano in Italy.

Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A is an architect and planner with extensive experience in urban planning and design, business management and real estate development, and academia. He is a Professor of Urban Design at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Mark has been a visiting lecturer at the University of Florida, Georgia Tech, Architectural Association in London, the University of São Paulo in Brazil, and Politecnico di Milano in Italy.

People must have quickly realized the opportunities inherent in the design and planning of the pilotis feature because intensive patrols of the buildings and grounds began shortly after Pruitt-Igoe opened, even before any welfare recipients were allowed to live there. Former residents indicate these stairwells/elevators were problematic spaces from the very beginning (Photograph:

People must have quickly realized the opportunities inherent in the design and planning of the pilotis feature because intensive patrols of the buildings and grounds began shortly after Pruitt-Igoe opened, even before any welfare recipients were allowed to live there. Former residents indicate these stairwells/elevators were problematic spaces from the very beginning (Photograph:

Social malaise accelerated at Pruitt-Igoe during the 1960s even as residents maintained some apartment interiors until a cataclysmic mechanical failure in 1968 (watch a 5-minute KMOX news report on YouTube

Social malaise accelerated at Pruitt-Igoe during the 1960s even as residents maintained some apartment interiors until a cataclysmic mechanical failure in 1968 (watch a 5-minute KMOX news report on YouTube