FROM THE VAULT | Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia by Robert Fishman

FROM THE VAULT | Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia by Robert Fishman

Review by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

I’ve been an admirer of historian Robert Fishman ever since reading Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century (MIT Press, 1982) in the early 90s but especially after hearing him speak at CNU20 in West Palm Beach, FL in 2012. Given this, I was a naturally excited to read this book when I came across it many years after its publication. However, I have to begrudgingly admit I was mostly underwhelmed by Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (Basic Books, 1987). Partially, this is a matter of timing. When Fishman wrote and published this book in the late 1980s, it seemed like the cumulative apex of suburban expansion and urban decline in the United States. In hindsight, Fishman’s history of suburbia come across as a dated, unconditional surrender to what must have seemed to many people at the time as the inevitable (despite the ‘fall’ mentioned in book’s title). Of course, we now realize there was still a significant part of the story waiting to play out over the subsequent three decades (see New Urbanism/Smart Growth, collapse of the mortgage bond market, and 2008 Financial Crisis).

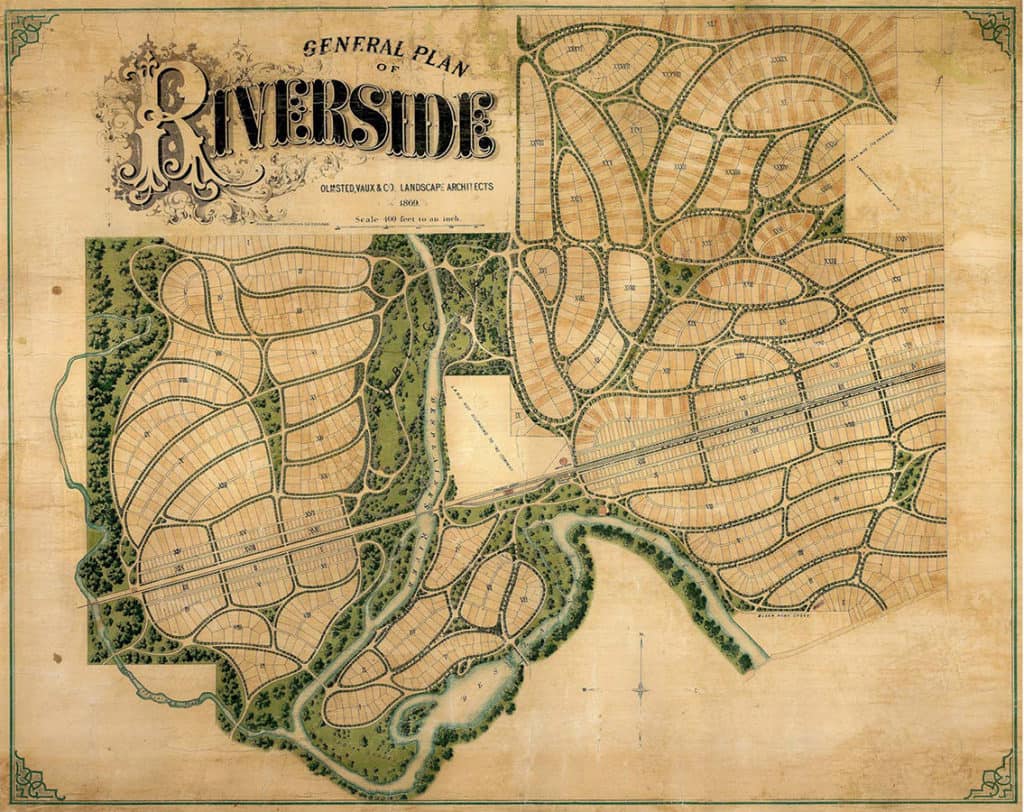

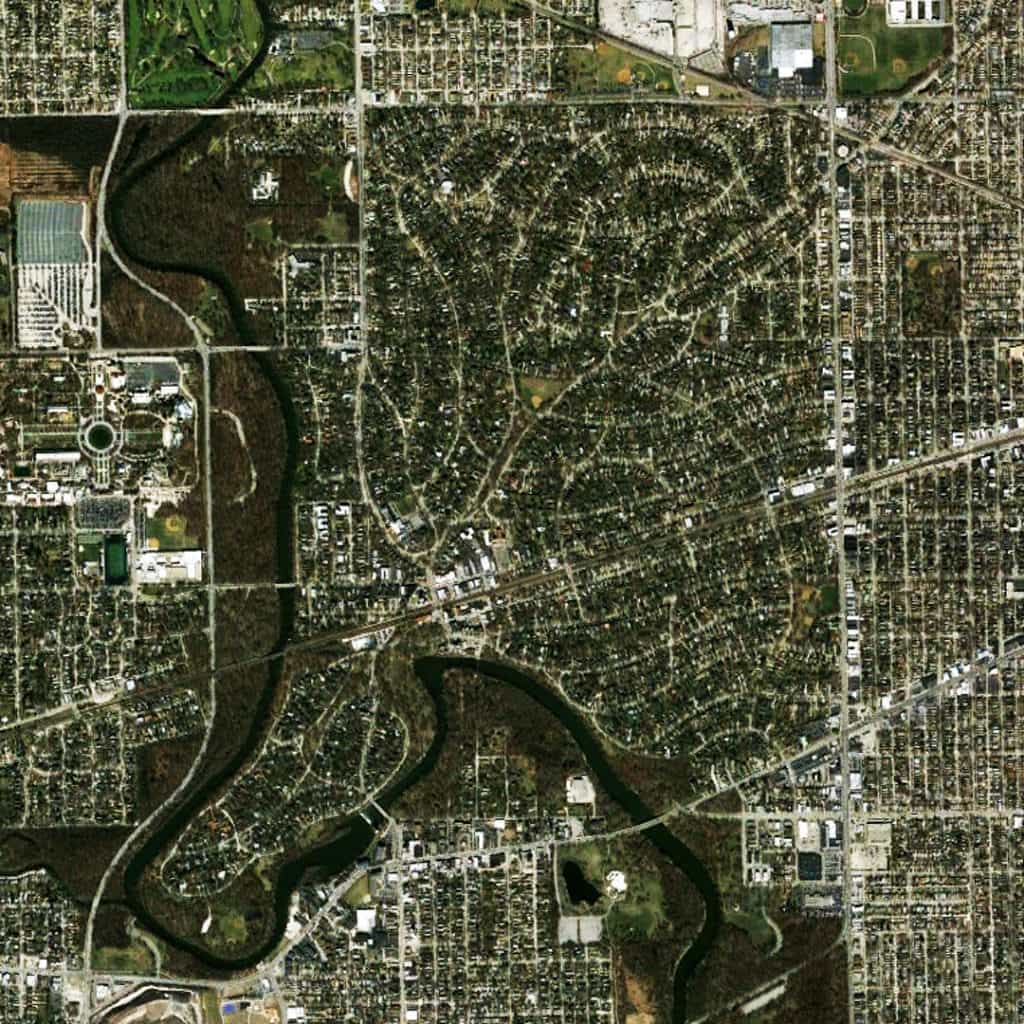

However, it is not all a matter of timing. Fishman is so determined to fit his subject into the thematic structure began in Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century that he tends to cast aside any evidence contrary to his central thesis, especially when it comes to the American experience of suburbia. For example, you will not find the phrases ‘exclusionary zoning’ or ‘restrictive covenants’ anywhere in Bourgeois Utopias, which seems like an odd oversight for a purported history of suburbia. Fishman also oddly ignores ample evidence in the historical record (as well as John Reps’ seminal histories The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States and Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning) that there were, in fact, only a few examples of the modern American suburb type (Llewellyn Park, New Jersey and Frederick Law Olmsted’s Riverside, Illinois being the most obvious 19th century forerunners) before World War II because the regular grid dominated in American land speculation activities until the onset of the Great Depression in 1929.

This creates a problem because Fishman has to, more or less, cast aside the narrow, formal definition of suburbia he adopts at the start of the book when discussing early suburbs in London and Manchester, England for a much looser definition (basically, any single family home with front yard setbacks) when approaching the American experience, especially in Los Angeles. In fact, Fishman’s entire chapter on Los Angeles reads as a regurgitation of Reyner Banham’s arguments in Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971) so both have the same flaws in underestimating the power of the urban grid. It is also another case in bad timing since Mike Davis’ City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles was published only a few years later in 1990. Davis’ book has its own flaws but it is an invaluable resource for understanding the historical development of urban form in Los Angeles including the role of water pilfering in that city as well as the insidious role of the automobile industry in the Red Car’s demise.

By far, the best and most compelling part of Bourgeois Utopias is Fishman’s research on early suburbs in England during 18th and 19th century and Olmsted’s mid-19th century plan for Riverside, Illinois (basically, pages 1-148). Indeed, any reader should be able to sense the author’s greater interest in these pre-20th century examples compared to the amalgamated cancer of 20th century suburbanization in the United States, when it seems as if Fishman is trying to ‘run out the clock’ on the book. In fact, if Fishman wasn’t so determined to ambitiously fit this topic into the ‘utopia’ theme, he might have been better served to limit his historical research to these pre-20th century examples. Fishman astutely identifies the changing nature of family related to longer life expectancy during the 18th and 19th century in England as the social origins for suburbia. Fishman briefly mentions life expectancy (which seems far more important than the words given in this book) before devoting most of his time to the evolution of familial relations in the workplace and/or home. Fishman also makes an important, useful distinction between the productive and consumptive suburb that has broader implications than spelled out in the book. It is fascinating research, which alone makes the book worth the effort. In the end, though, there are some good parts (Anglo examples) and some head-scratching parts (American examples) in Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia so the book deserves, at best, only a 3-star rating.

Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia

Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia

by Robert Fishman

Basic Books, 1987

Paperback, 272 pages, English

ISBN-10: 0465007473

ISBN-13: 978-0465007479

You can purchase Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia from Amazon here.

From the Vault is a series from the Outlaw Urbanist in which we review art, architectural and urban design texts, with an emphasis on the obscure and forgotten, found in second-hand bookstores.

“Call the police, I’m sure it must be a crime,” turned around and walked back the way we came out of the neighborhood, all the while dutifully carrying my doggy poop bag and carefully navigating through multiple piles of dog shit in the neighborhood common areas. Needless to say, Izzy and I will never be walking in that neighborhood again (not that it was ever likely anyway).

“Call the police, I’m sure it must be a crime,” turned around and walked back the way we came out of the neighborhood, all the while dutifully carrying my doggy poop bag and carefully navigating through multiple piles of dog shit in the neighborhood common areas. Needless to say, Izzy and I will never be walking in that neighborhood again (not that it was ever likely anyway).