“I wanna feel sunlight on my face. I see the dust-cloud,

Disappear without a trace. I wanna take shelter,

From the poison rain, Where the streets have no name.”

— Where the Streets Have No Name, U2

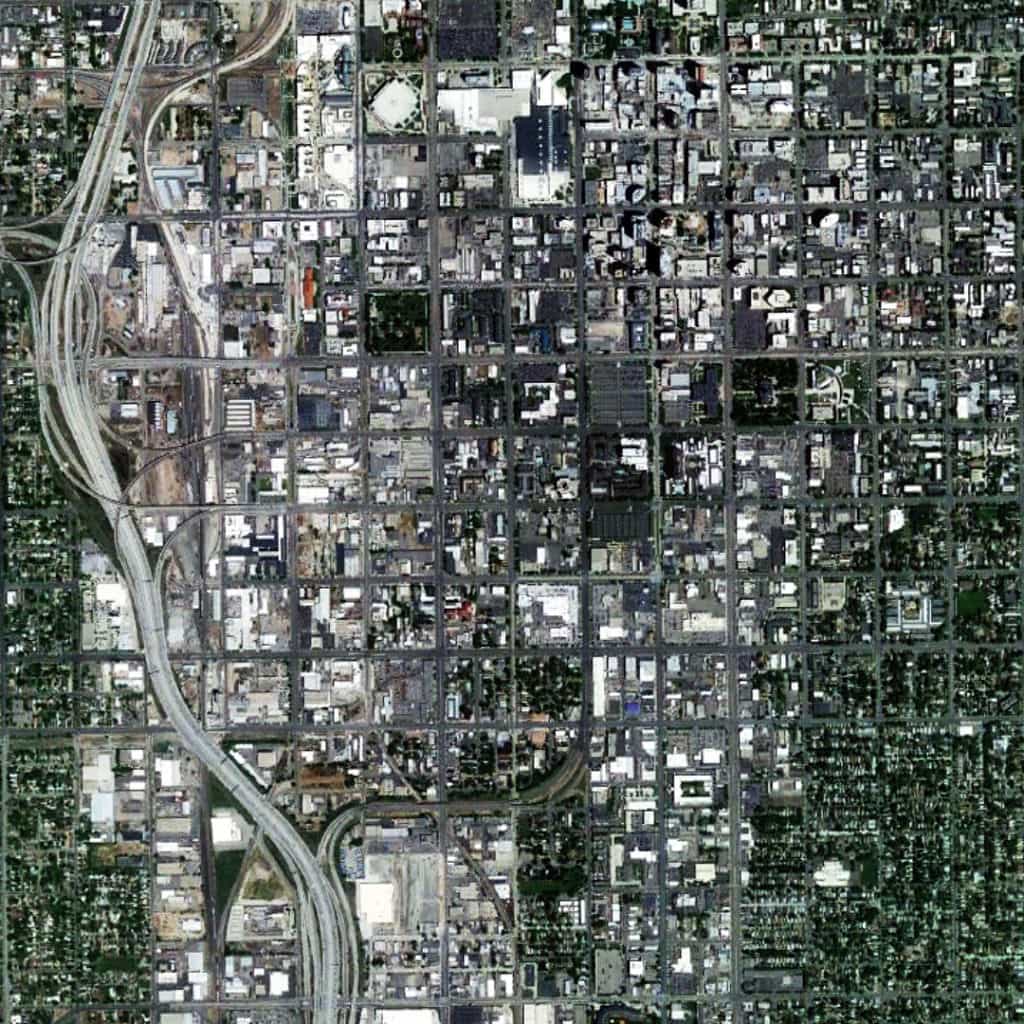

Urban Patterns | Las Vegas, Nevada USA

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

There is a lot that can be said – and has been said over the years – about the “Modern Babylon’ known as Las Vegas, Nevada. Las Vegas comes from the Spanish, who used artesian wells for water in the area, supporting green meadows (vegas in Spanish), on journeys along the Old Spanish Trail from Texas during the 19th century. Mormons were the first to settle in the area in 1855 when Brigham Young assigned missionaries from Salt Lake City to convert the local Indian population to Mormonism. They constructed a fort near the current downtown area, which served as a stopover for travelers between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. The missionaries abandoned the settlement a couple of years later during the Utah War (a bloodless confrontation between Mormon settlers and the U.S. Government).

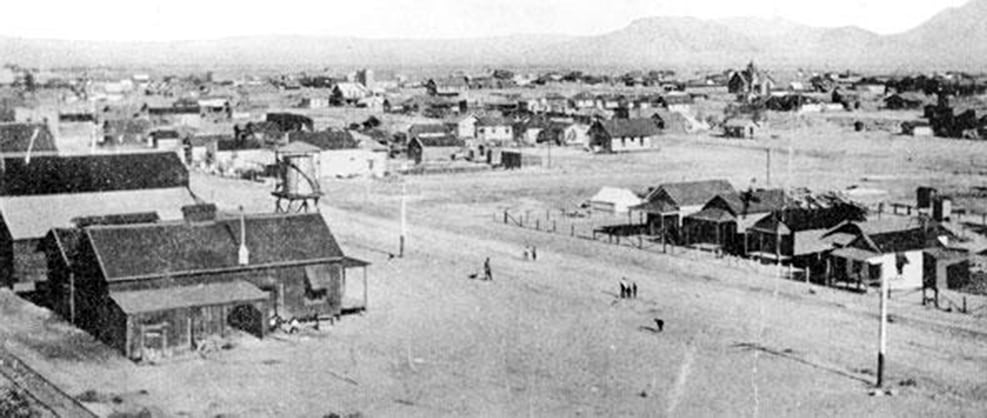

Las Vegas became a railroad town in 1905 when it was still a crossroads hamlet and briefly prospered in the early 20th century due to mining activities in the area, and as a rail stopover between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. Official incorporation of the city occurred in 1911 and the State of Nevada legalized gambling in 1931. This led to the construction of the first casino-hotels in Las Vegas, which gained success and notoriety due to organized crime figures such as Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky. Siegel and Lansky were associated with the Genovese crime family (one of New York City’s Five Families of the Cosa Nostra, i.e. American Mafia). However, Mormon-owned banks fronted Siegel and Lansky, which provided legitimacy for their activities. Siegel was a driving force behind large-scale development of Las Vegas until his murder in 1947. The large casino-hotels led to an explosion of urban growth that eventually made Las Vegas one of the top entertainment and tourist destinations in the world.

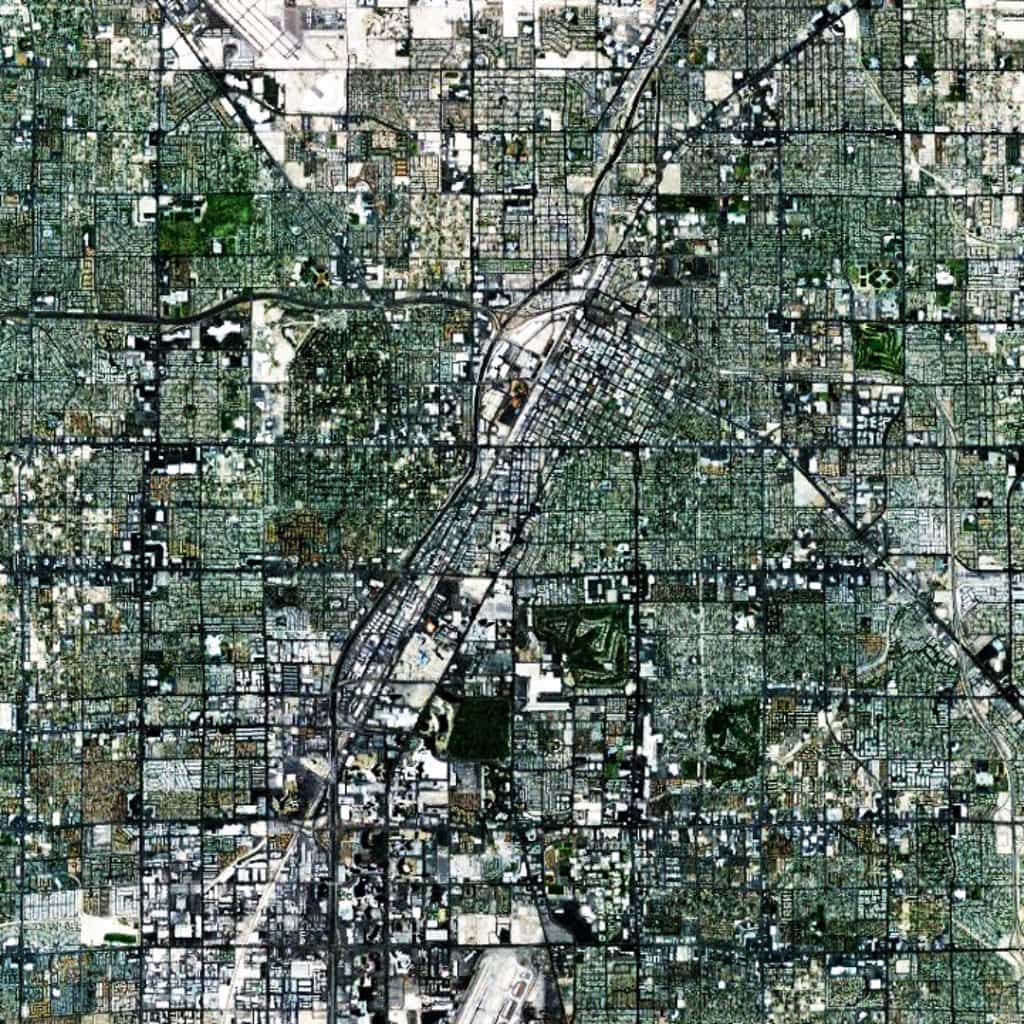

Having said all this, we are going to limit today’s Urban Patterns post about Las Vegas to three things. First, a large amount of green visible in the above satellite image is completely man-made (either rooftops or lawns). Las Vegas is located in an arid basin on the desert floor, surrounded by dry mountains. Much of the landscape is rocky and dusty and the environment is dominated by desert vegetation. To borrow from Baudrillard, the greenery of Las Vegas is a landscaper’s simulacrum of a natural vegetation that otherwise does not exist in the area independent of man-made irrigation systems (much like Los Angeles). Second, is the readily-apparent importance of the radial streets (including a significant portion of Las Vegas Boulevard) feeding into the CBD/historic area (offset grid at the center). Lastly, is the indelible mark that has emerged over time on the urban landscape due to the national grid system imposed by the 1785 Land Ordinance, as evidenced by the large-scale orthogonal grid pattern around the CBD/historic area. These are only three interesting things about the city’s urban pattern. Las Vegas is an endlessly fascinating city for so many different reasons.

(Updated: May 18, 2017)

Urban Patterns is a series of posts from The Outlaw Urbanist presenting interesting examples of terrestrial patterns shaped by human intervention in the urban landscape over time.

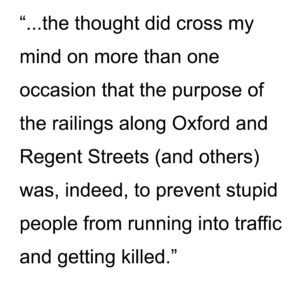

No doubt the reason I found this rant so funny was, having lived in London for 8 years, the thought did cross my mind on more than one occasion that the purpose of the railings along Oxford and Regent Streets (and others) was, indeed, to prevent stupid people from running into traffic and getting killed. Of course, this is not the case. Instead, the purpose of the railings is to corral pedestrians on the sidewalk in areas with high foot traffic (like pigs in a pen) so the majority of street space is reserved for automobile traffic. London’s railings are fundamentally anti-pedestrian, pro-automobile planning measures. God forbid if pedestrians occupy more of the street space for their use to the detriment of keeping traffic moving! So, the real purpose of the railings was to prevent stupid drivers in 5-ton death machines from killing pedestrians, awarding ‘exclusivity’ of street space to these drivers when we should be slowing the traffic down in deference to pedestrians. In the late 1990s, London has begun to learn and adjust to this lesson. When I visit London (hopefully) sometime in the next 4-6 months, I’m eager to see for myself how far they have taken the lesson over the last decade. I like to think Eddie’s satirical rant played a small role in changing the dynamic.

No doubt the reason I found this rant so funny was, having lived in London for 8 years, the thought did cross my mind on more than one occasion that the purpose of the railings along Oxford and Regent Streets (and others) was, indeed, to prevent stupid people from running into traffic and getting killed. Of course, this is not the case. Instead, the purpose of the railings is to corral pedestrians on the sidewalk in areas with high foot traffic (like pigs in a pen) so the majority of street space is reserved for automobile traffic. London’s railings are fundamentally anti-pedestrian, pro-automobile planning measures. God forbid if pedestrians occupy more of the street space for their use to the detriment of keeping traffic moving! So, the real purpose of the railings was to prevent stupid drivers in 5-ton death machines from killing pedestrians, awarding ‘exclusivity’ of street space to these drivers when we should be slowing the traffic down in deference to pedestrians. In the late 1990s, London has begun to learn and adjust to this lesson. When I visit London (hopefully) sometime in the next 4-6 months, I’m eager to see for myself how far they have taken the lesson over the last decade. I like to think Eddie’s satirical rant played a small role in changing the dynamic.

Olga Rozanova’s City (1916) is a wonderful abstract painting, which takes the city as its subject. Her city is all kinetic energy, the canvas almost ‘alive’ with movement. Her painting builds on the Cubist tendency to compress time and space into a single glance at a subject, which conveys a plenitude of information to the viewer. This, in itself, builds on the earlier Impressionist technique, which included movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience in the painting. However, in the case of Cubism, it is not the movement of human perception that depicted in the painting but rather the movement and energy inherent in the subject itself across time and space, which is both compressed and captured in the representation. Olga Rozanova’s City is a brilliant look at

Olga Rozanova’s City (1916) is a wonderful abstract painting, which takes the city as its subject. Her city is all kinetic energy, the canvas almost ‘alive’ with movement. Her painting builds on the Cubist tendency to compress time and space into a single glance at a subject, which conveys a plenitude of information to the viewer. This, in itself, builds on the earlier Impressionist technique, which included movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience in the painting. However, in the case of Cubism, it is not the movement of human perception that depicted in the painting but rather the movement and energy inherent in the subject itself across time and space, which is both compressed and captured in the representation. Olga Rozanova’s City is a brilliant look at

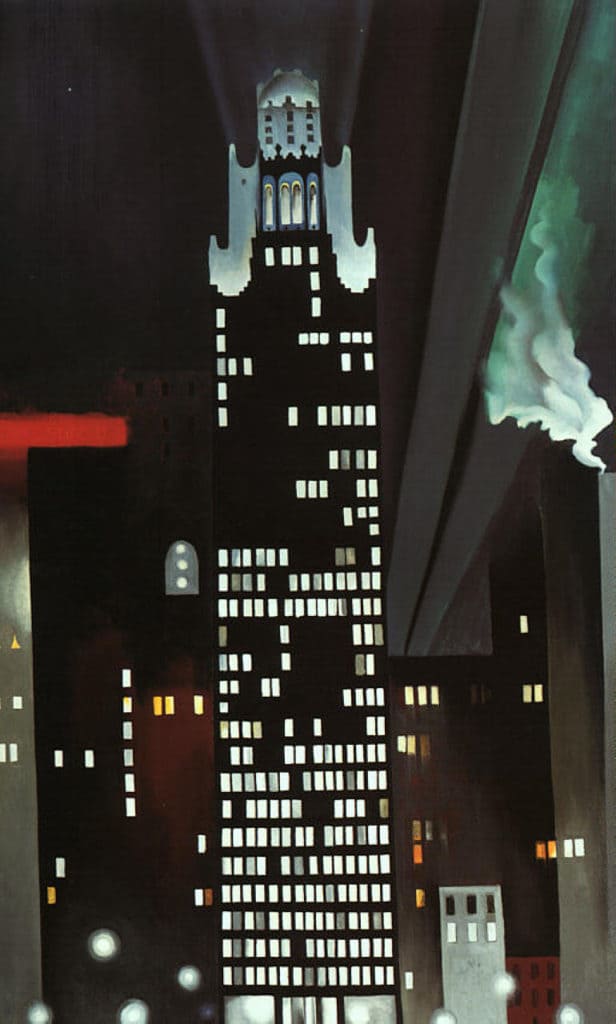

We can say this with some confidence because if you were to remove all of the ‘painted light’ from this painting, only a black canvas would remain. It is this ‘painted light’ that provides a subtle richness and contextual depth to the best of O’Keeffe’s cityscape paintings. Later, we will see more explicit examples in her other paintings, for example in The Shelton with Sunspots (1926). In this sense, the subject is the artifice of form emerging from the arrangement of light. The fact the words ‘Radiator Building’ and ‘New York’ are in the title of the painting is completely inconsequential and accidental to the subject of the piece. It is also misleading on O’Keeffe’s part by naming the painting in this manner. However, this is completely consistent with her tendency to be opaque when it comes to the subject matter of her own paintings. As architects and planners, O’Keeffe’s painting shows us how we can expand our perception of the city beyond the conventional (form) to see its richness in other, more subtle – and, perhaps, richer – ways (light).

We can say this with some confidence because if you were to remove all of the ‘painted light’ from this painting, only a black canvas would remain. It is this ‘painted light’ that provides a subtle richness and contextual depth to the best of O’Keeffe’s cityscape paintings. Later, we will see more explicit examples in her other paintings, for example in The Shelton with Sunspots (1926). In this sense, the subject is the artifice of form emerging from the arrangement of light. The fact the words ‘Radiator Building’ and ‘New York’ are in the title of the painting is completely inconsequential and accidental to the subject of the piece. It is also misleading on O’Keeffe’s part by naming the painting in this manner. However, this is completely consistent with her tendency to be opaque when it comes to the subject matter of her own paintings. As architects and planners, O’Keeffe’s painting shows us how we can expand our perception of the city beyond the conventional (form) to see its richness in other, more subtle – and, perhaps, richer – ways (light).