On Space | The Structural City

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

The spatial experience of the city is a child’s playground of structures, of a faraway multitude and its near-invariants, a beingness trivial and noble, earthy in its dimensions but astral in meaning. The foreground is composed as the background is configured, imposed by the actions of local actors but emerging on a global stage of meaning and consequence. We are its actors and the playwright, telling the story and bringing it to life for an audience that is ourselves, as if performance could thrive across a mirror of timeless depth and perception, an infinite recursion writ large and whispered softly. The city is a presentation – and representation – of our best and worst selves, of our past and our future, denoting significance in the moment of the present, the here and now of our lives, of the everyday errands of individual importance but (seemingly) societal inconsequentiality. We think, therefore we are but also we move, here we were and will be. These abstract and material constructions of the city reach for the horizon and to the sky, never attaining either but embedding the object with a purpose, with a meaning, and with a question that simultaneously transcends and surrenders to the entities populating the streets, spaces, and buildings of the city. It is transcendence and capitulation to the physical and the spatial, to the kinetic energy of movement and the static inertia of place, to the functioning of the urban object, that at once determines and allows its formation and articulation.

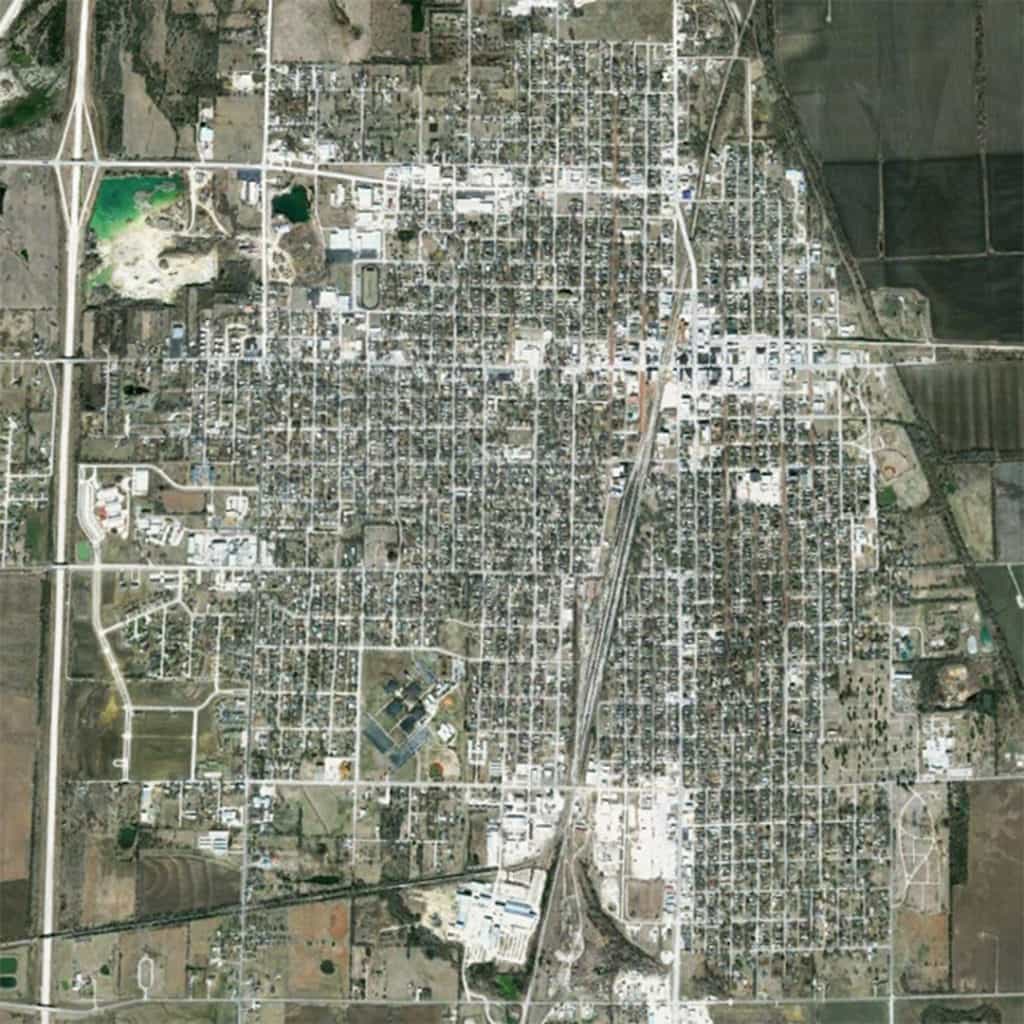

It is an entity that births and devours itself, this Urban Ouroboros, forming protective walls against unseen intruders and unknown dangers. We are the beginning of our story, its past prologue. We are at the center of our story, its extant climax. We are the edge of our story, its future denouement. But it is not the genesis, neither the center nor even the edge that carries the value of our actions. It is the path lying in-between, from where to here to there, from the mere act of marking a path in the landscape to the volatile core of our beingness in the city, and further to the tranquil border that defines the state of being within or without. The grid is the thing. The grid is its genesis, it generates and swathes, offering a translucent skin, which reveals the heart and muscle, pulse and rhythm of the city. Its skin is spelled out in the superordination of geometries both great and small, widths of mysteriously known paths, lengths of promising unspoken journeys, and rigid alignments of mass and light. Hierarchies are simply defined, and structures are mystically revealed in the body of the city; a city of collective memory, of shared purpose, and of forgotten desires that we carry along with us on the path. It is achieved with frightening efficiency, which we consciously retreat from, to our own detriment, yet cannot deny, to our own blessing. The dynamics of the city rise and fall with our intentions, with our mistakes, and with our unending beauty in the body of the collective. Its effects are systematic across and embedded within body and mind, perpetuating the rapid spread of malignancies and their antidote. A city is an object of cosmic imagination grounded in a foundation of our earthly desires and guttural sins. It all these things, and more… much more.

On Space is a regular series of philosophical posts from The Outlaw Urbanist. These short articles (usually about 500 words) are in draft form so ideas, suggestions, thoughts and constructive criticism are welcome.

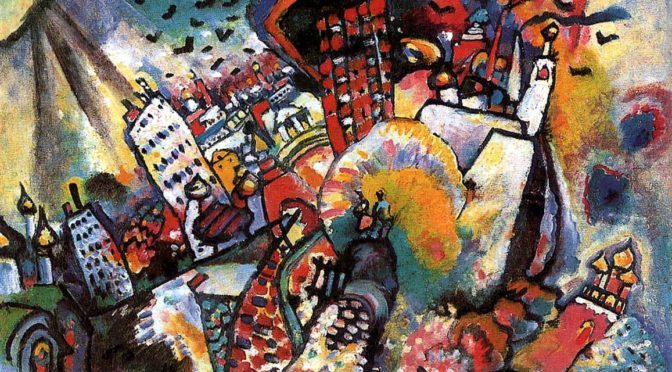

Moscow I contains some of the same romantic fairy-tale qualities of his earlier paintings, fused with dramatic forms and colors. “The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot, which, like a wild tuba, sets all one’s soul vibrating” (Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” 360).

Moscow I contains some of the same romantic fairy-tale qualities of his earlier paintings, fused with dramatic forms and colors. “The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot, which, like a wild tuba, sets all one’s soul vibrating” (Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” 360). About Wassily Kandinsky

About Wassily Kandinsky