“Oh brother, are you gonna leave me,

Wastin´ away on the streets of Philadelphia.”

— Streets of Philadelphia, Bruce Springsteen

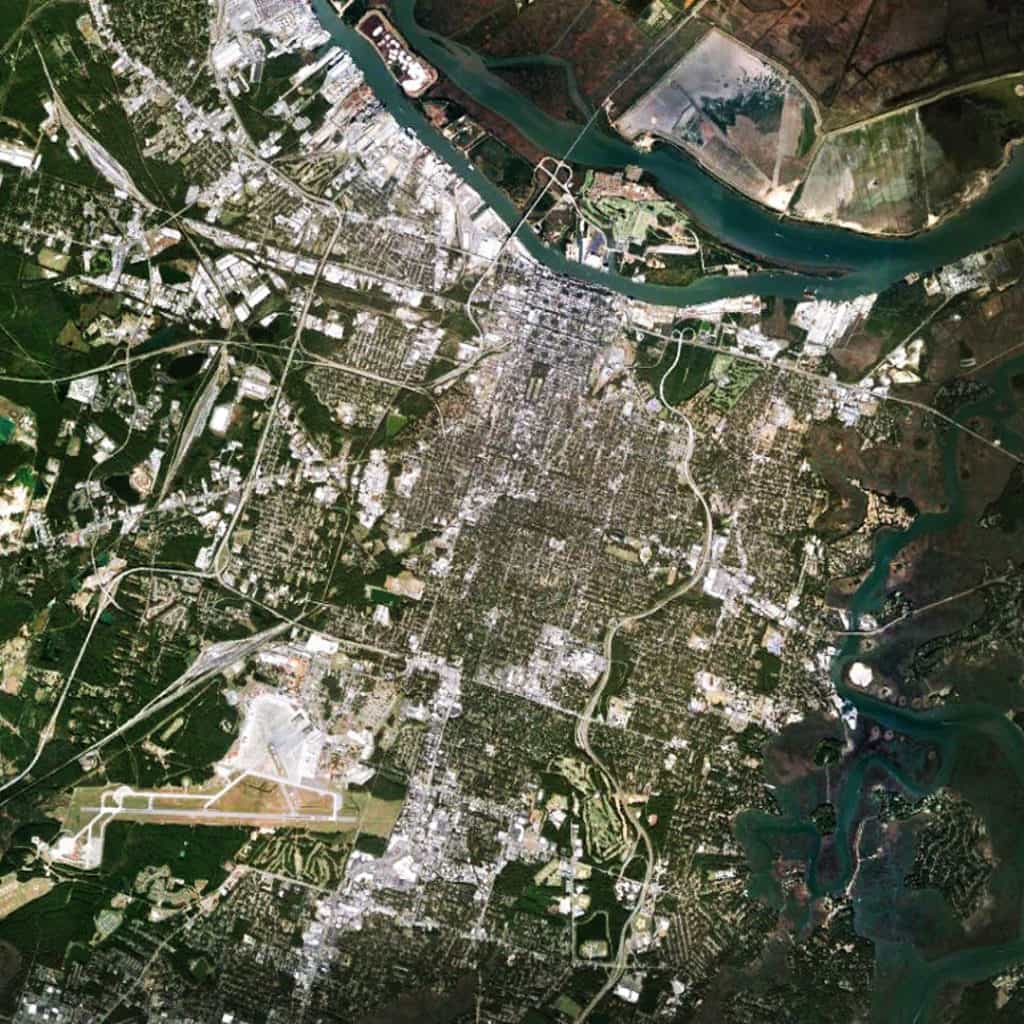

Urban Patterns | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

Philadelphia is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the fifth-most populous city in the United States, with an estimated population of 1,567,442 and more than 6 million in the seventh-largest metropolitan statistical area, as of 2015. Philadelphia is the economic and cultural anchor of the Delaware Valley—a region located in the Northeastern United States at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers with 7.2 million people residing in the eighth-largest combined statistical area in the United States. In 1682, William Penn, an English Quaker, founded the city to serve as capital of the Pennsylvania Colony. Philadelphia played an instrumental role in the American Revolution as a meeting place for the Founding Fathers of the United States, who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the Constitution in 1787 (Source: Wikipedia).

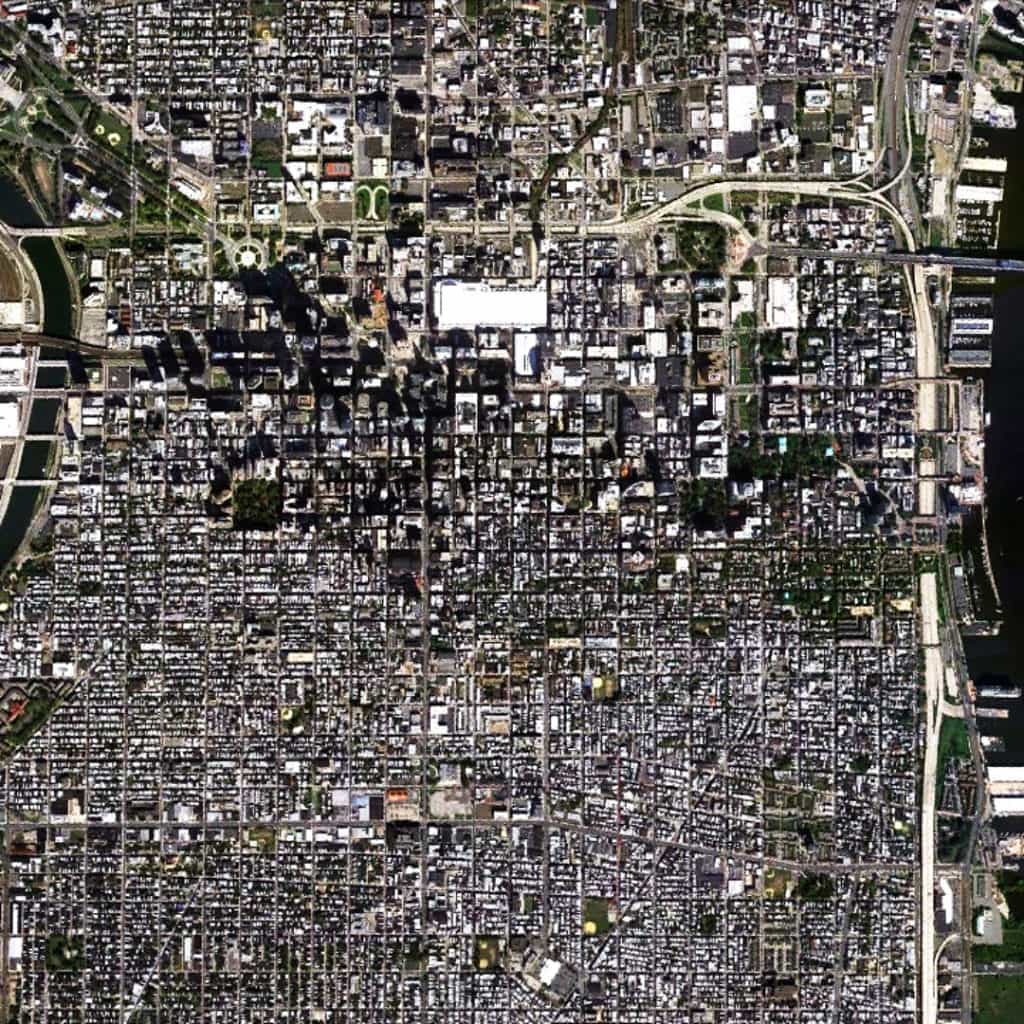

There are two remarkable yet seemingly contradictory things about the urban pattern in Philadelphia; in particular, within the bounds of William Penn’s original 1682 plan for the city. First, is the remarkable degree to which the plan has changed over more than 330 years of development. Most often, this has occurred through the manipulation of block sizes (upsizing and subdividing of urban blocks) even if the Vine Street Expressway (Interstate 676) and Delaware Expressway (Interstate 95) ringing the bounds of the original plan might, at first glance, draw the eye to these large-scale interventions. Second, is the remarkable degree to which the integrity of the original Penn plan for the city has endured literally thousands of small-scale interventions over more than 330 years of development. Taken together, this points to something even more remarkable, which is the instrumental power of the regular grid to be simultaneously flexible for and resilient to change over time.

(Updated: April 1, 2017)

Urban Patterns is a series of posts from The Outlaw Urbanist presenting interesting examples of terrestrial patterns shaped by human intervention in the urban landscape over time.