The American Planning Association’s Standing Committee for the Refutation of Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities during a recent difficult meeting. According to an unnamed source who attended the committee’s most recent deliberations, “It’s a madhouse, a MADHOUSE!”

Monthly Archives: January 2013

20 Must-Read Texts for Urban Planners (#1-10)

20 Must-Read Texts for Urban Planners (#1-10)

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Lists are often a handy tool to spark a discussion, debate, or even an argument. The purpose of this list is pretty straightforward, i.e. what should you have read. Of course, in limiting the list to a mere 20 texts (books and articles), there is no possible way it can be exhaustive. There are a lot of interesting texts out there from a lot of different perspectives (some better than others). It is also true that compiling such a list will inevitably reveal the particular biases of the person preparing the compilation (like revealing your iTunes playlist). In the end, it is only their opinion. There’s no way around it. This list demonstrates a clear bias towards texts about the relationship between the physical fabric of cities and their spatio-functional nature with a particular emphasis on first-hand observation of how things really work. Because of this, perhaps the most surprising thing about this list is how few texts there are by people who identify themselves as planners (or perhaps not, depending on your perspective). Finally, as with most lists, it is wise to reserve the right to amend/update said list in order to allow for any unfortunate oversights. Having said that, the list is an absolute good. The list is life. All around its margins lies suburban sprawl. Let the making of lists 1-10 begin…

10. “The Origin and Spread of the Grid-Pattern Town” (1946) by Dan Stanislawski

An old text, perhaps obscure to many and only familiar to a few, “The Origin and Spread of the Grid-Pattern Town” is one of the earliest and most thorough reviews of the evolution of regular grid town planning in the world. Yes, Stanislawski subscribes the spread of regular grid town planning to a process of historical diffusion, which Spiro Kostoff (see below) correctly points out nobody believes in any more. Despite this flaw, Stanislawski’s review is surprisingly comprehensive, for the most part. Stanislawski does seem to gloss over medieval town platting, see Maurice Beresford’s 1967 New Towns of the Middle Ages: Town Plantation in England, Wales and Gascony. However, some later writers ignore all together clear examples of regular grid planning in certain regions of the world (the Orient, for example). Stanislawski’s article is still a valuable resource today for any reader interested in the regular grid as long as they are careful about filtering out some of his misplaced – discredited today – ideas (for example, historical diffusion or the importance of Hippodamus).

The article is available here

9. “Savannah and the Issue of Precedent: City Plan as Resource” (1993) by Stanford Anderson

John Reps in his historical narrative of American town planning (see below) is enchanted with the historical ward plan of Savannah, as are many architects, urban designers, and planners. Reps is equally mystified (and a little despondent) about why the Savannah plan was not more influential in the history of American town planning. In “Savannah and the Issue of Precedent: City Plan as Resource,” Anderson offers a succinct and brilliant analysis about how the ward plan of Savannah operated in terms of street alignments and dwelling entrance locations working together to structure the outside-to-inside ‘assimilation’ of strangers into the town (principally in relation to the port). In generic terms, Savannah appears to be quite typical of a lot of waterfront settlements in American planning. However, its detailed specifications for squares and constitution are rigid, making it an inflexible model for early American town development (for example, compared to the flexibility of the Philadelphia or Spanish Laws of the Indies models). Anderson’s article should be on the standard reading list for any academic program in planning.

The article is available on Google Books here

8. The Practice of Local Government Planning (2000)

It is one thing to complain about how planning works in the United States. However, it is hypocritical to complain without really understanding how planning works in the United States. The Practice of Local Government Planning offers a clear solution. For years, the various incarnations of the “green book” have been the go-to source for American planners to immerse themselves in the full scope of their profession in the United States. This Municipal Management Series book is the first one that any planner will open when seeking to pass the AICP exam. It is comprehensive and detailed. Warning: it is a very, very dry read. It is also extremely careful to remain neutral when presenting a picture about the way things work, i.e. this is what it is, not this is the right way to do things. In this sense, it is value-free and empty at its core. Nonetheless, it remains an invaluable resource for any planner, or anyone wanting to understand planners.

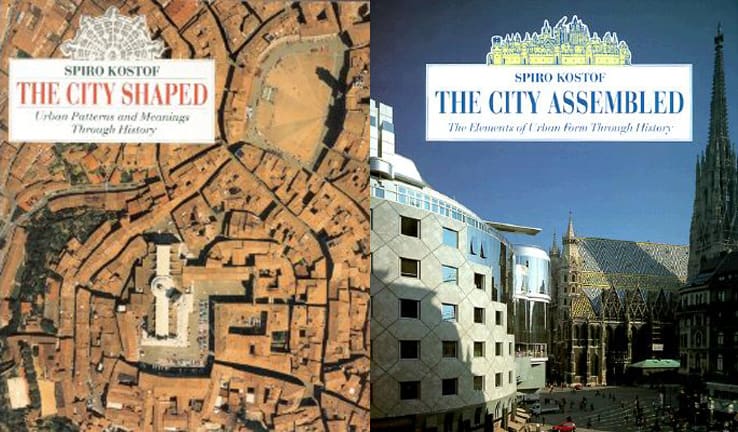

7. The City Assembled: The Elements of Urban Form Through History (1992) by Spiro Kostoff

6. The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History (1991) by Spiro Kostoff

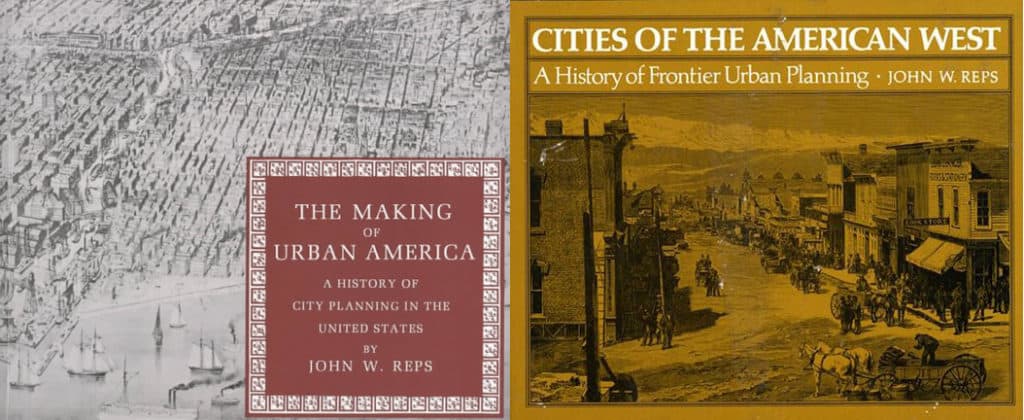

5. Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning (1979) by John W. Reps

4. The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States (1965) by John W. Reps

Kostoff’s The City Shaped/The City Assembled are the crucial books about the history of town planning in the world for any urban planner to have on their bookshelves. Reps’ The Making of Urban America/Cities of the American West about the history of town planning in the United States are the crucial books for any urban planner to also have on their bookshelves. If an urban planner does not have these books on their bookshelves, it is reasonable to question the quality of said planner. There are other good historical narratives out there on the subject (Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s The Matrix of Man or Eisner and Gallion’s The Urban Pattern, for example). However, Kostoff and Reps’ books are the most comprehensive and thorough for their particular subjects. All four books incorporate hundreds of plans/plats and photographs to tell the story of town planning in the United States and world at large. They also offer detailed historical information (especially Reps) about the people and events involved in building our cities. Sometimes they are insightful and sometimes they are mistaken. For example, despite his protestations about the dichotomy so prevalent in town planning, Kostoff remains firmly entrapped within that dichotomy, i.e. ‘organic’ and ‘regular’ cities. Reps correctly points out the historical importance of William Penn’s plan of Philadelphia but misstates the reasons, assigning to Philadelphia what should have more appropriately been given to the Nine Square Plan of New Haven and the Spanish Law of the Indies, which Kostoff correctly emphasizes (though we are discussing subtle but important degrees of difference instead of a chasm in thought between both writers). When he ventures away from historical narrative and facts into the realm of opinion, Reps is often prone to undervalue the functional power of regular grid. However, these are endlessly useful texts for anyone interested in cities and the collection of plans and other historical documents (bird’s eye views) are a wonderful resource for any planner to have readily at hand.

3. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture (1996) by Bill Hillier

A purist could argue that anyone interested in space syntax should start with The Social Logic of Space (1984) by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson. The Social Logic of Space is an important book where Hillier and Hanson spell out a lot of groundwork for the theoretical and mathematical foundations of space syntax. However, they do so to a level of detail that some readers might find off-putting. Even Hillier and Hanson admit that one of its chapters is practically unreadable because it is so dry with technical detail. If you want to learn about the space syntax approach and some of its early, important findings without getting bogged down in the detail, then you will be better served by starting with Hillier’s Space is the Machine. Besides, Hillier is always careful about repeating the ‘big picture’ items that arose from The Social Logic of Space (beady ring settlements, restricted random process, and so on), so you won’t miss too much. For planners, the most important chapters in Space is the Machine to get immersed are about cities as movement economies, whether architecture can cause social malaise, and the fundamental city. There are plenty of goodies for architects as well. Space is the Machine is a must-read for anyone serious about a scientific approach to the built environment.

Space is the Machine is available here

2. The City: Suggestions for Investigation of Human Behavior in the Urban Environment (1925) by Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess

One of the planning profession’s biggest problems is that the Chicago School (the sociologists Park and Burgess and their colleague, Homer Hoyt, see sector model of city growth, who together were the founders of human ecology) got so much right from the very beginning that there wasn’t anywhere for planning to go from there but down. Of course, planning theory proceeded to accomplish this downhill spiral with great vigor and spectacularly bad results (see the second half of the 20th century). With the advent of the computer processor, Park and Burgess’ approach may appear somewhat quaint to modern eyes. However, the essentials about the city are there. More importantly, Park and Burgess never divorce the socio-economic nature of the city from its physical form but view them as intimately bound together. An important book and somewhat underrated in today’s world by planners, though it’s difficult to understand why or how that should be the case.

1. The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs

Big surprise, huh? These days it seems like anyone interested in cities is obsessed with Jane Jacobs, either in implementing and promoting her ideas or in feverishly going to ridiculous lengths trying to refute them (one might call it Jacobs Derangement Syndrome). Indeed, this obsession in itself is a testament to the power of her book. Ironically, for its time, the most novel thing Jacobs did was she dared to look out her window and observe how things were really working out there on the street. It’s a sad statement on the planning profession that this was somehow viewed as a sacrilege when the book was first published and, to a certain extent, this perception endures even today. I mean, how dare she actually suggest we evaluate (and, by implication, take responsibility for) the social and economic consequences of our planning decisions. The Death and Life of Great American Cities is the essential book for any planner.

McMansions Return: Big Houses Come Back | Yahoo! Finance

In other news today, the Hershey Company released the startling results of a survey that indicates 98% of children want candy for every meal on an everyday basis. This appears to confirm the findings of the most recent surveys by the American Dental Association and Halloween Industry Association (yes, it really does exist) that asked similar questions of American children.  However, it does seem to contradict the findings of a recent survey by the International Association of Ice Cream Distributors & Vendors that suggested 96% of American children actually want ice cream for every meal. A spokesman for the American Dental Association was kind enough to take time away from a vacation on his yacht off the coast of Barbados to comment, “We don’t see how the results of these different surveys about what American children want to be provided for their daily nutrient requirements can be viewed as in conflict with one another in any feasible manner.”

However, it does seem to contradict the findings of a recent survey by the International Association of Ice Cream Distributors & Vendors that suggested 96% of American children actually want ice cream for every meal. A spokesman for the American Dental Association was kind enough to take time away from a vacation on his yacht off the coast of Barbados to comment, “We don’t see how the results of these different surveys about what American children want to be provided for their daily nutrient requirements can be viewed as in conflict with one another in any feasible manner.”

There are so many depressing aspects of this story and the media coverage that the McMansion part only begins to scratch the surface of what is wrong with this picture.

Read the full article here: McMansions Return: Big Houses Come Back | Yahoo! Finance.

20 Must-Read Texts for Urban Planners (#11-20)

20 Must-Read Texts for Urban Planners (#11-20)

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist Contributor

Lists are often a handy tool to spark a discussion, debate, or even an argument. The purpose of this list is pretty straightforward, i.e. what should you have read. Of course, in limiting the list to a mere 20 texts (books and articles), there is no possible way it can be exhaustive. There are a lot of interesting texts out there from a lot of different perspectives (some better than others). It is also true that compiling such a list will inevitably reveal the particular biases of the person preparing the compilation (like revealing your iTunes playlist). In the end, it is only their opinion. There’s no way around it. This list demonstrates a clear bias towards texts about the relationship between the physical fabric of cities and their spatio-functional nature with a particular emphasis on first-hand observation of how things really work. Because of this, perhaps the most surprising thing about this list is how few texts there are by people who identify themselves as planners (or perhaps not, depending on your perspective). Finally, as with most lists, it is wise to reserve the right to amend/update said list in order to allow for any unfortunate oversights. Having said that, the list is an absolute good. The list is life. All around its margins lies suburban sprawl. Let the making of lists begin…

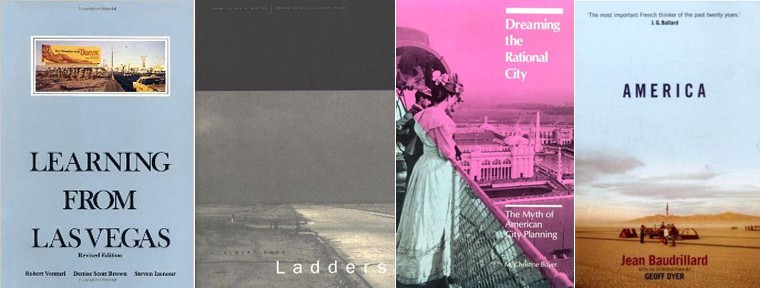

20. Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (1972) by Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown

Venturi et al expand the arguments first outlined in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture in 1966 to the urban level with their seminal study of Las Vegas. Only on these terms, it is an interesting read. However, dig a little deeper beneath the surface and into their wonderful series of figure-ground representations of spatial functioning on, along and adjacent to the Las Vegas Strip. You will discover Venturi et al concede – almost casually – the functional dynamics of how the strip operates to the realm of urban space and pattern in order to quickly focus on their arguments on what really interests them, i.e. the semantic nature of architectural form. A surface reading of only what Venturi et al writes misses a lot of the richness found within since there is a whole other book hidden based on what they are not saying but merely showing you.

19. The Concept of Dwelling: on the way to figurative architecture (1985) by Christian Norberg-Schulz

One always has to be careful with phenomenology because, by definition, almost everything written is subjective and open to vast differences in interpretation. However, much like the previous entry on this list, if a reader is willing to dig beneath of the surface and give thoughtful consideration about what, at first, appears to be purposefully opaque writing, then often there are rich rewards to be discovered. Norberg-Schulz’s The Concept of Dwelling is one of the best examples.

18. Ladders, Architecture at Rice 34 (1996) by Albert Pope

It is something of a mystery why this book seems to be sorely under-appreciated and underrated outside of Houston, Texas. Pope’s study about the physical pattern of the American urban fabric is a fascinating read. Urban planners – especially American ones – could do a lot worse than read an entire book examining the physical pattern of the urban fabric in cities they are suppose to be planning; in fact, they have and do so regularly.

17. Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning (1983) by M. Christine Boyer

Boyer’s The City of Collective Memory seems to overshadow her earlier book, which is a shame. Her history of the planning profession in the United States is a devastating and powerful critique that is as relevant today as when it was first published. It is also a much better book than The City of Collective Memory.

16. America (1988) by Jean Baudrillard

The best planners are good sociologists and the best sociologists are great observers. Baudrillard was one of the best and keenest observers of human society and its meaning. Baudrillard wraps his observations within a flamboyant, often elegant, and occasionally beautiful use of language. It is not always clear whether the flurries of linguistic gymnastics are really his or is the result of translating from French into English. However, the results often amount to genius. In America, Baudrillard’s compare and contrast of Paris, New York, and Los Angeles yields rich rewards to any planner who dares to pay attention.

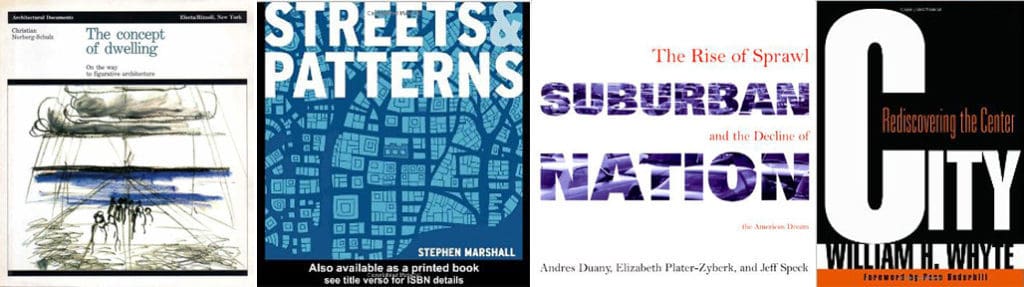

15. Streets and Patterns (2005) by Stephen Marshall

The first half of Marshall’s book is a brilliant review and analysis of where we are and how we got here. The second half – focusing on possible solutions – descends into being only interesting.

14. City: Rediscovering the Center (1989) by William H. Whyte

Whyte’s study of informal, social interaction in public spaces is a case study in urban observation that any planner should seek to take into account and emulate. Yes, sometimes Whyte’s conclusions are too localized about the attributes of the space itself than how it fits into the pattern of a larger urban context. However, at other times, his findings are remarkable for their common sense. For example, people in public spaces will move chairs for the purpose of promoting interaction rather than locate their interactions where chairs are located or tend to locate social interaction in areas of high movement like street corners. Anyone who has ever tried to move their way through to party – mumbling to themselves “why do people have to stop here to talk” – will understand many of Whyte’s observations about human nature and informal interaction are rock solid. Whyte’s City can almost be read as a companion piece to Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

13. “The Architecture of Community: Some New Proposals on the Social Consequences of Architectural and Planning Decisions” (1987) by Julienne Hanson and Bill Hillier, Architecture and Comportement, Architecture and Behaviour, 3(3): 251-273.

Download the article here: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/5265/1/5265.pdf

There are many texts by a lot of people about why space syntax is important. However, few have driven home the point more powerfully and succinctly than this early article by Hanson and Hillier about the social consequences of design decisions for Modern housing estates (projects) in the UK. In doing so, Hanson and Hillier add considerable intellectual and quantitative heft to Jane Jacobs’ arguments about urban safety and “eyes on the street” in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. This article will probably be obscure to most planners, especially in the USA. The real crime is it’s rarely read outside of the space syntax community itself.

12. Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream (2000) by Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and Jeff Speck

A purist will probably argue when it comes to New Urbanism, start with The New Urbanism by Peter Katz. If you’re not really keen on appetizers, then go straight to the main meal. Suburban Nation is not only about what is the New Urbanism but also delves into the argument about why we need the New Urbanism today. New Urbanism does not always get it right. Does anybody? However, there shouldn’t be any doubt that it is heading in the right direction and that is a huge achievement in itself.

11. “Transect Planning” (2002) by Andres Duany and Emily E. Talen. APA Journal, 68(3): 245-266.

Duany and Talen elegantly translate a fundamental aspect about the spatio-functioning of streets tailored to urban form into understandable terms for public officials, urban designers and planners who are still trapped in – or refuse to leave – the box of the Euclidean zoning model and the arbitrary roadway classifications almost universally associated with it over the last half-century. In terms of the prevailing planning paradigm afflicting our cities, transect planning is the metaphorical equivalent of Duany and Talen pushing a Trojan horse inside the city gates. The more applied, the less tenable becomes the roadway classifications associated with the Euclidean zoning model. Beware of New Urbanists bearing gifts (i.e. methodology).

Coming Soon: 20 Must-Read Texts for Urban Planners (#1-10)!

America, Saudi Arabia of tomorrow | CNN.com

If this proves true, the geopolitical implications – and those for American cities – are profound. Fingers crossed…

Read the full article here: America, the Saudi Arabia of tomorrow – CNN.com.