Planning Naked | June 2016

Planning Naked | June 2016

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Your (hopefully) hilarious guide to everything about the latest issue of APA’s Planning Magazine.

The Rise of the Aqua Planner. “Water Everywhere” in From the Desk of APA’s Executive Director section by James M. Drinan (pp. 3) discusses the intense focus on water issues during sessions of the recent APA National Conference. While the subject of water management and resources is, of course, important, especially in light of rapid urbanization and population growth around the world, I can’t figure out if the APA was being intentionally ironic, cleverly subversive, or just plain clueless by setting this conversation in Phoenix, Arizona. A city on the edge of an arid desert that gets a lot of its water from the Colorado River and probably should not exist at all based the precepts of generic function. It suspiciously sounds like APA is more interested in creating another specialized planning silo – the Aqua Planner.

June. 2016. A date. Which will live. In infamy. APA is finally forced to publish the obituary of Robert Moses’ ideas in “Farewell, Robert Moses Parkway North” by Tara Nurin (pp. 6). More like ‘good riddance’ since the real infamy is it took a quarter of a century for this project to get off the ground.

The Advance of Shared Space. “Chicago Neighborhood Puts Pedestrians First” by Allen Zeyher (pp. 7) details the shared space conversion of a three-block stretch of Argyle Street in Chicago. Pedestrians First? Isn’t that slogan some sort of right-wing synthesis of vehophobia (“fear of driving”) and xenophobia (“fear of outsiders”)? Brad McCauley at Site Design Group, Ltd. offers the absolutely priceless quote of the article: “in pedestrian-heavy corridors, it’s a no-brainer to reclaim space that was formerly given over to cars,” which implicitly confirms our suspicion that the overwhelming majority of urban planners do not possess a brain. Perhaps a trip to Emerald City to see the Wizard is in order?

States lead. Federal hampers. Oh wait, State hampers, too. At first glance, there is more evidence in the News Brief section (pp. 7) that there isn’t any problem the Federal government won’t try to regulate its way out of (e.g. more EPA requirements) whereas it is the States that are really leading (e.g. Colorado Supreme Courts overturns local fracking ban)… except for the last news item about the Texas Department of Transportation adding ‘informal’ lanes by using inside shoulders during rush hour for motorists to double average speeds and produce “smooth sailing.” That’s called medicating the symptoms, not curing the disease. At least, TexDOT have their ‘evidence’ for another costly lane widening project. Let’s be honest, motorists were probably already using the inside shoulders and TexDOT merely acknowledged the fait accompli.

Speaking of fait accompli. “Tactical Urbanism Goes Mainstream” by Jake Blumgart in the News and Legal Lessons section (pp. 8) seems to stamp tactical urbanism with APA’s approval because the brand has now been proven capable of securing money for things that don’t, in fact, have anything to do with tactical urbanism. The Philadelphia example cited in the article is for pool amenity improvements, not tactical urbanism. The $184,080 granted in Detroit isn’t for tactical urbanism, it’s nominally ‘planning for tactical urbanism’ but the first project discussed is – yes, you guessed it – pool amenity improvements. It’s disturbing how concepts get twisted to mean almost anything you want when the money gets involved in the United States.

Real Reporting. In “Scalia’s Land-Use Legacy,” William Fulton briefly reviews the legacy of the recently deceased Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia on land use law for the Legal Lessons section (pp. 9). It is a well-written, objective piece about, primarily, the Nollan and Lucas decisions. Fulton discusses their legal importance and Scalia’s intellectual role in crafting the majority decisions. The article is informative while blessedly free of ‘hidden’ agendas or positions. Ah, real reporting!

Tsk-tsk. Aaaaaarrrrrrrggggggghhhhhh. “Mixed Income, Mixed Results” by Craig Guillot (pp. 10-17) discusses the combination, for good or ill, of market rate and targeted affordable housing in developments. Housing policies in the United States from the Federal level to State and local government has been completely ass-backwards ever since the 1949 Housing Act and APA has been – and continues to be – complicit in perpetuating this ass-backwardness. All of the evidence you need is this quote, “Brennan says funding has been a barrier,” which again boils everything down to ‘give us more money.’ Giullot’s article therefore ably covers all of the problems this ass-backwards approach entails and reaps without ever addressing the core problem that everyone is basically talking out of their ass when it comes to housing. The short answer is found in the scale of developments, build-out times, land appreciation, and recognizing that a city does not ever, ever, ever remain statically frozen in time or character. The purposeful convolution of this issue is frustrating beyond belief and a direct consequence of early 20th century Euclidean zoning and suburban land tenure theories. But, by all means, continue to fiddle with market and affordable housing percentages and waste the next 50 years as well.

Here’s Your Consolidation Prize. “Separated City” by Lee R. Epstein (pp. 18-23) about Capetown in South Africa is actually a really interesting, informative article. Epstein seems to skip over the fact (or maybe, I missed it) that cities like Capetown actually represent traditional urban patterns in most of the world where lower income people live at the edges (e.g. suburbs) and higher income people live in the center. In contrast, the American urban model became inverted due to suburbanization during the post-war period. However, what’s really suspicious is how this story on Capetown immediately follows Guillot’s article about mixed income neighborhood planning efforts in US cities. Am I being paranoid that this article represents a consolidation prize to make American urban planners feel better about themselves (“See, it could be worse. Just look at Capetown, South Africa”)? Maybe, maybe not.

My God! Real Science in Planning Magazine! The use of biometrics to track human eye movement in the built environment is not new (perhaps it’s new to the APA and/or Americans). It’s been around for a while now – being worked on at University College London using virtual reality 20 years ago – in one form or another. It’s a fascinating area of research about the built environment but we need to be careful to fully appreciate the implications and not assume it’s an issue of quantity [“No wonder visitors from around the world like walking through Venice or Copenhagen — there’s so much (our emphasis) there to stimulate our sensory system, no matter one’s native language, culture, or personal history”]. There is a LOT of meat in this subject, too much to go into here but you can look at some of the work of Dr. Ruth Conroy Dalton at the Northumbria University and Dr. Beatrix Emo, Cahir of Cognitive Science at ETH Zurich. The key takeaway from the article for architects and planners right now is this quote: “I realized how people are really attracted to people.”

My God! Housing Sanity in Planning Magazine! Finally, someone articulates a reasonable perspective about the issues of housing in the Viewpoint section, “The New Home Ownership Reality” by Professor Anthony Nelson (pp. 48) of the University of Arizona. Professor Nelson does not implicitly tackle the house size part of the equation (e.g. tiny houses/small house movement) but any discussion about affordability has to begin with rental housing and ownership of affordably sized homes. Professor Nelson’s Viewpoint article is a good place to start.

Planning Naked is an article with observations and comments about a recent issue of Planning: The Magazine of the American Planning Association.

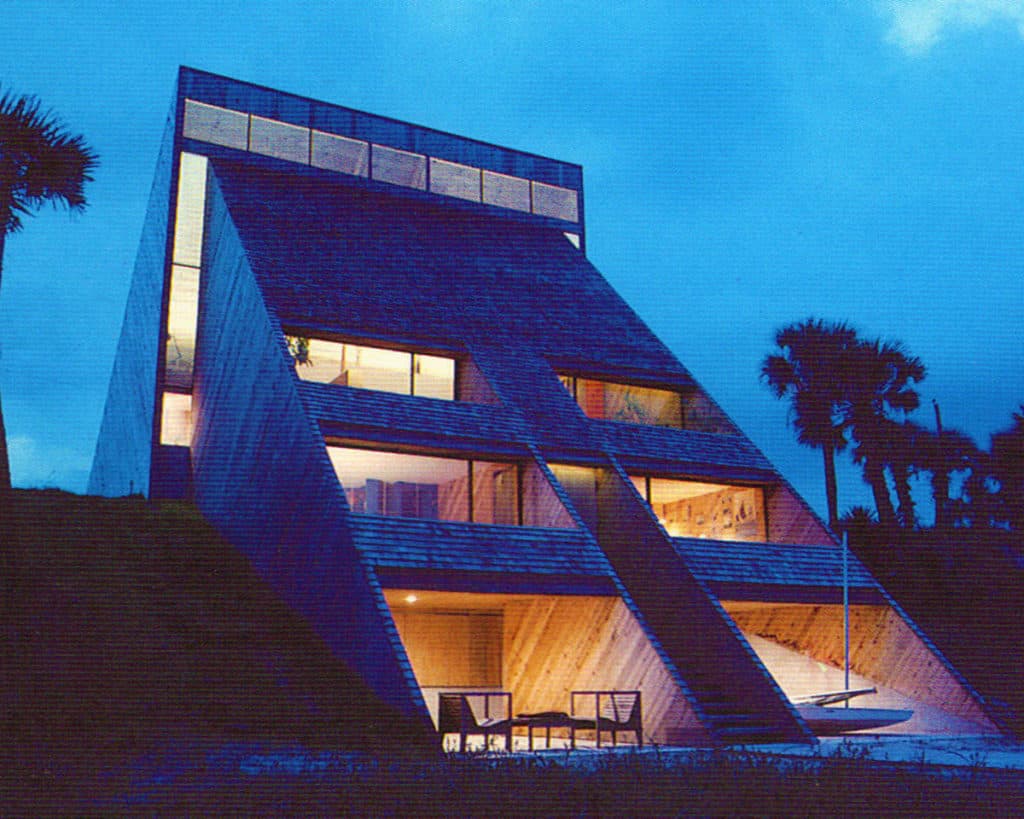

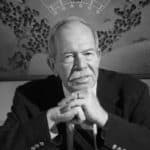

William Morgan was an American Modernist architect based in Jacksonville, Florida, who passed away earlier this year (December 14, 1930 – January 18, 2016). Three of his designs are included on the Florida Association of the American Institute of Architects list of Florida’s Top 100 Buildings including The Williamson House in Ponte Vedra Beach, Morgan’s Residence in Atlantic Beach, and Dickinson Hall at the University of Florida. Morgan grew up in Jacksonville and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University before serving in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War. After the war, he returned to Harvard to study architecture. He studied in Italy on a Fulbright Scholarship and then returned to Jacksonville to open his architecture practice in 1961 (Source: Wikipedia; Photograph: Florida Times-Union).

William Morgan was an American Modernist architect based in Jacksonville, Florida, who passed away earlier this year (December 14, 1930 – January 18, 2016). Three of his designs are included on the Florida Association of the American Institute of Architects list of Florida’s Top 100 Buildings including The Williamson House in Ponte Vedra Beach, Morgan’s Residence in Atlantic Beach, and Dickinson Hall at the University of Florida. Morgan grew up in Jacksonville and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University before serving in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War. After the war, he returned to Harvard to study architecture. He studied in Italy on a Fulbright Scholarship and then returned to Jacksonville to open his architecture practice in 1961 (Source: Wikipedia; Photograph: Florida Times-Union).