The New Paleolithicism for Society: A Satire

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

Our long history of urban experiences has climaxed in an unbearable state of being for humanity. Today, one out of every two people in the world live in a city; by 2030, six out of every ten people will do so; and, by 2050, seven out of every ten (Source: World Health Organization). Why do we relentlessly pursue the destruction of our own species with this rapid urbanization? The time has come for widespread changes about the way – and where – we live. We must be quick to take measures now to deurbanize the world before we fall into an irrevocable vortex of endless crime, casual murder, and widespread drug use. Why has the urban experience failed? Television, news, and the Internet provide the answer. After all, everything we see and read on television, news and Internet is the verified truth. Simply out, the city is unsafe. Being safe – the state of not ever being exposed to the threat of physical, mental or emotional loss, injury or distress – is, as we all know, the ultimate goal of human existence. Safety is more valuable than faith, love or hope, except for faith in one’s safety, love of one’s safety, and hope for one’s safety. Theft, drugs, and murder are unfortunate facts of everyday life in the city. And the litter of our Victorian attitudes falters in the face of our particular urbane prostitutions. We must suppress these carnal desires, willingly fed by the city.

There is a story told in every city about a murder occurring in a public space as dozens of witnesses watched, willfully ignoring the horrible act and all failing to assist the victim. What is the solution to this problem? Avoiding large crowds might provide a temporary salve. Crowds are only found in the city. Some suggest a personal bodyguard for every man, woman and child, which would not only reduce the crime rate but also bring the benefit of returning restless populations to full employment after the horror of the Great Recession. But who would guard the guards? You see the logistical dilemma. Others argue the solution – intimately tied to the proliferation of personal protection services – is the right to bear arms. Indeed, the use of firearms from the cradle to the tomb would greatly contribute to decreasing incidences of crime in our urban centers.

But a plethora of bodyguards and firearms can only produce new problems for our urban centers, increasing demand over available supply for people and guns, and crippling our substandard pubic transportation systems (you see, two now travel where before there was only one). The problematic nature of public transportation first became fully realized with the appearance of mass-produced automobiles during the early 20th century. Highways are always too small, cars are never big enough, public rail is grossly unsanitary, and buses are forever late. A new approach to transportation is needed. A formidable suggestion lies in eliminating all forms of mechanical transport from the planet. In its place, a new human species would emerge, walking its way to physical fitness, excellent health and, no doubt, unquestioned beauty. The elimination of the automobile will also contribute to a dramatic decrease in teenage pregnancy (think about it). With the passing of the automobile, its supporting apparatus – the factory – would also disappear into the mists of the distant past. Since the Industrial Revolution first darkened our blue skies into a shadowy black, pollution has been of paramount importance for survival of the species. With the demise of all mechanical transports, the formidable pro-pollution lobby will, at last, fall to ruin. Unused factories shall collapse as humanity fully embraces a new multi-nomadic modal transportation. At last, we will have achieved a real solution to the dark veil of global warming/climate change descending over us since the medieval days of 1988. However, these are only partial solutions.

But a plethora of bodyguards and firearms can only produce new problems for our urban centers, increasing demand over available supply for people and guns, and crippling our substandard pubic transportation systems (you see, two now travel where before there was only one). The problematic nature of public transportation first became fully realized with the appearance of mass-produced automobiles during the early 20th century. Highways are always too small, cars are never big enough, public rail is grossly unsanitary, and buses are forever late. A new approach to transportation is needed. A formidable suggestion lies in eliminating all forms of mechanical transport from the planet. In its place, a new human species would emerge, walking its way to physical fitness, excellent health and, no doubt, unquestioned beauty. The elimination of the automobile will also contribute to a dramatic decrease in teenage pregnancy (think about it). With the passing of the automobile, its supporting apparatus – the factory – would also disappear into the mists of the distant past. Since the Industrial Revolution first darkened our blue skies into a shadowy black, pollution has been of paramount importance for survival of the species. With the demise of all mechanical transports, the formidable pro-pollution lobby will, at last, fall to ruin. Unused factories shall collapse as humanity fully embraces a new multi-nomadic modal transportation. At last, we will have achieved a real solution to the dark veil of global warming/climate change descending over us since the medieval days of 1988. However, these are only partial solutions.

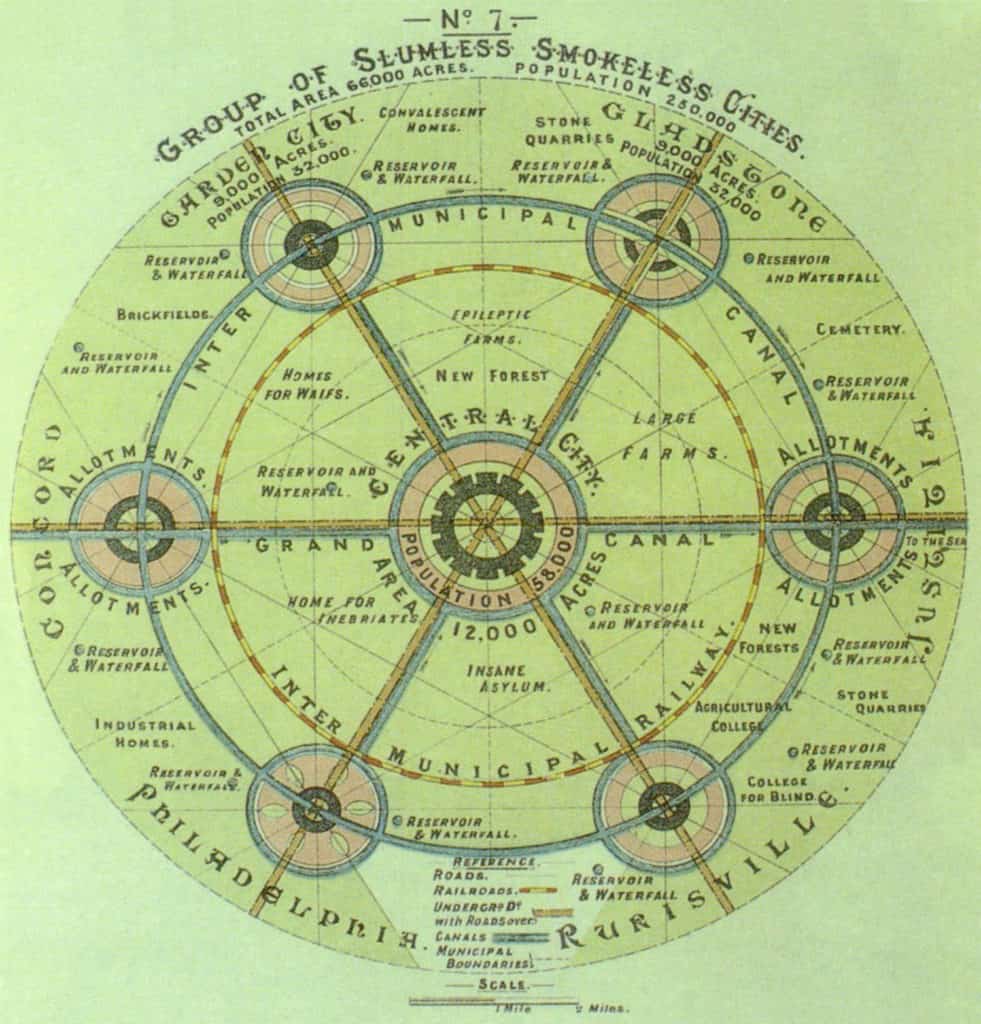

A more permanent solution is needed. In fact, so intransigent are the problems we face that it can only be concluded the solution lies in the construct of the city itself, or more accurately its destruction. A radical alternative is needed. We must begin with completely dismantling the major urban centers of the world. Suburban sprawl can only exist in the presence of an urban center. If we eliminate urban centers, then sprawl becomes effective dispersal in realizing a new innovative land management policy, which can be described as the New Paleolithicism.

What is the vision for New Paleolithicism, you ask? Our slogan shall be: 160 Acres, four guns, and three Domestic Partners for Every Household! Of course, we shall have to revise the definition of household since the word ‘tribe’ might cause some people to ignore the beauty of this solution. In this sense, a household means approximately 15 people occupying their own 160 acres on the planet. This ratio of 160 acres for every 15 people is based on the current density of human population to land mass. Every heterosexual male would be provided with two heterosexual females in order to perpetuate reproduction of the species. However, heterosexual male-to-female ratio in gross terms will not support such a system. This is where our LGBT brethren become a vitally important component in the equation. Some households must be headed and composed of domestic LGBT partnerships in order to make the ratio of heterosexual males and females work for this new society. Some households might even be LBGT/heterosexual hybrids (“Polysexual Households”). Naturally, since these commusexual and polysexual households will not need to support as many offspring as their heterosexual brethren, they shall be allotted the least desirable locations on the planet. Our LGBT brethren must climb this ‘mountain’ and cross this ‘desert’ on behalf of humanity. They will understand the necessity. The dismantling of the urban centers and the elimination of all mechanical transports shall facilitate clear air and healthy bodies, perhaps even leading to the end of Death itself. There can be no greater goal than being safe from the cold embrace of Death.

What is the vision for New Paleolithicism, you ask? Our slogan shall be: 160 Acres, four guns, and three Domestic Partners for Every Household! Of course, we shall have to revise the definition of household since the word ‘tribe’ might cause some people to ignore the beauty of this solution. In this sense, a household means approximately 15 people occupying their own 160 acres on the planet. This ratio of 160 acres for every 15 people is based on the current density of human population to land mass. Every heterosexual male would be provided with two heterosexual females in order to perpetuate reproduction of the species. However, heterosexual male-to-female ratio in gross terms will not support such a system. This is where our LGBT brethren become a vitally important component in the equation. Some households must be headed and composed of domestic LGBT partnerships in order to make the ratio of heterosexual males and females work for this new society. Some households might even be LBGT/heterosexual hybrids (“Polysexual Households”). Naturally, since these commusexual and polysexual households will not need to support as many offspring as their heterosexual brethren, they shall be allotted the least desirable locations on the planet. Our LGBT brethren must climb this ‘mountain’ and cross this ‘desert’ on behalf of humanity. They will understand the necessity. The dismantling of the urban centers and the elimination of all mechanical transports shall facilitate clear air and healthy bodies, perhaps even leading to the end of Death itself. There can be no greater goal than being safe from the cold embrace of Death.

In the grand scale of human history, it is in the cumulative effect of these measures where true success may be discovered. The New Paleolithicism is the final solution. We must accept deurbanization of the world has to take place. Eventually, we must retreat to the trees. Trees should be easy to re-adapt for human habitation. Instead of scarring the land with dwellings, we will once again become part of Nature, return to the trees, and only eat healthy foods; namely, nuts.

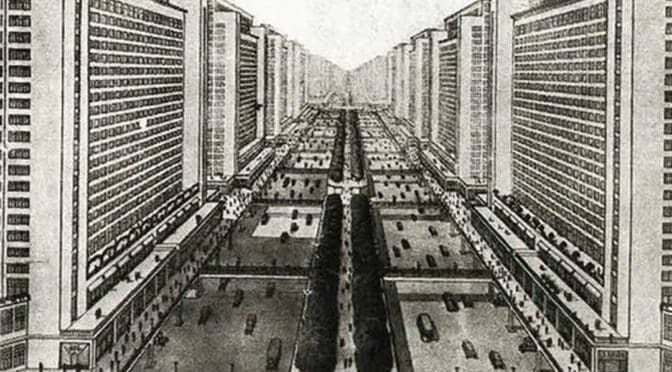

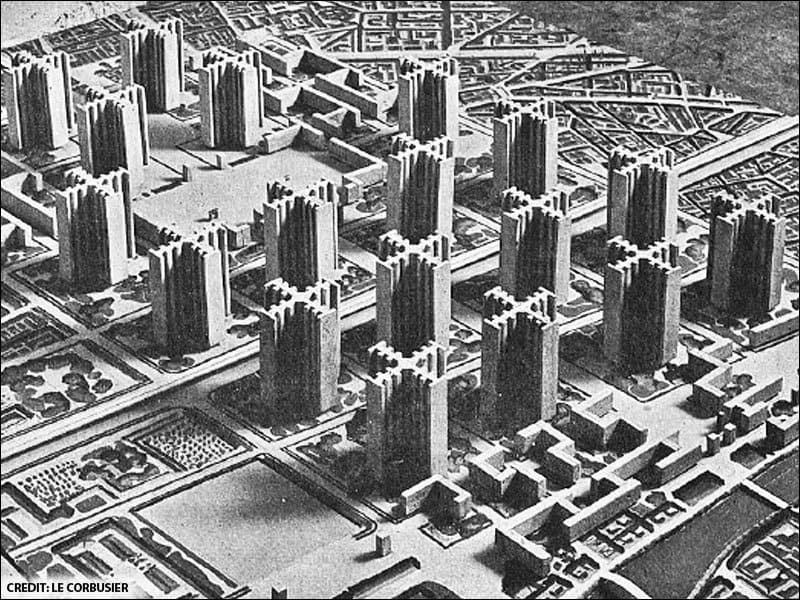

It was long on observation and way short on testing theoretical conjectures arising from those observations. Without scientific method to test its conjectures, Modernism in its infancy never made the crucial leap from normative to analytical theory. Instead, the subjective opinions of the CIAM architects and planners were embraced – sometimes blindly – by several generations of professionals in architecture and planning, and put into practice in hundreds of towns and cities. Today, for the most part, Modernism has finally been tested to destruction by our real world experience of its detrimental effects, though we continue to suffer from its remnants in the institutionalized dogma of planning education and the profession. Nonetheless, it has – at long last – made the transformation from normative to analytical theory and validated as a near-complete failure; at least in terms of town planning.

It was long on observation and way short on testing theoretical conjectures arising from those observations. Without scientific method to test its conjectures, Modernism in its infancy never made the crucial leap from normative to analytical theory. Instead, the subjective opinions of the CIAM architects and planners were embraced – sometimes blindly – by several generations of professionals in architecture and planning, and put into practice in hundreds of towns and cities. Today, for the most part, Modernism has finally been tested to destruction by our real world experience of its detrimental effects, though we continue to suffer from its remnants in the institutionalized dogma of planning education and the profession. Nonetheless, it has – at long last – made the transformation from normative to analytical theory and validated as a near-complete failure; at least in terms of town planning.

Right or wrong is the purview of politicians, philosophers and theologians. There are plenty – perhaps too many – planners and architects analogous to politicians, philosophers and theologians and not enough of the scientific variety. And too often, those that aspire to science remain mired in the trap of normative theory and institutionalized dogma. The Modernist hangover lingers in our approach to theory. But we require less subjective faith in our conjectures and more objective facts to test them. We persist with models that are colossal failures. When we are stuck in traffic, we feel like rats trapped in a maze. We apply normative theory to how we plan our transportation networks and fail to test the underlining conjecture. The robust power of GIS to store and organize vast amounts of information into graphical databases is touted as transforming the planning profession. But those that don’t understand science, mistake a tool of scientific method for theory. We project population years and decades into the future, yet fail to return to these projections to test and expose their (in)validity, refine the statistical method and increase the accuracy of future projections. And we hide the scientific failings of our profession behind the mantra, “it’s the standard.”

Right or wrong is the purview of politicians, philosophers and theologians. There are plenty – perhaps too many – planners and architects analogous to politicians, philosophers and theologians and not enough of the scientific variety. And too often, those that aspire to science remain mired in the trap of normative theory and institutionalized dogma. The Modernist hangover lingers in our approach to theory. But we require less subjective faith in our conjectures and more objective facts to test them. We persist with models that are colossal failures. When we are stuck in traffic, we feel like rats trapped in a maze. We apply normative theory to how we plan our transportation networks and fail to test the underlining conjecture. The robust power of GIS to store and organize vast amounts of information into graphical databases is touted as transforming the planning profession. But those that don’t understand science, mistake a tool of scientific method for theory. We project population years and decades into the future, yet fail to return to these projections to test and expose their (in)validity, refine the statistical method and increase the accuracy of future projections. And we hide the scientific failings of our profession behind the mantra, “it’s the standard.”

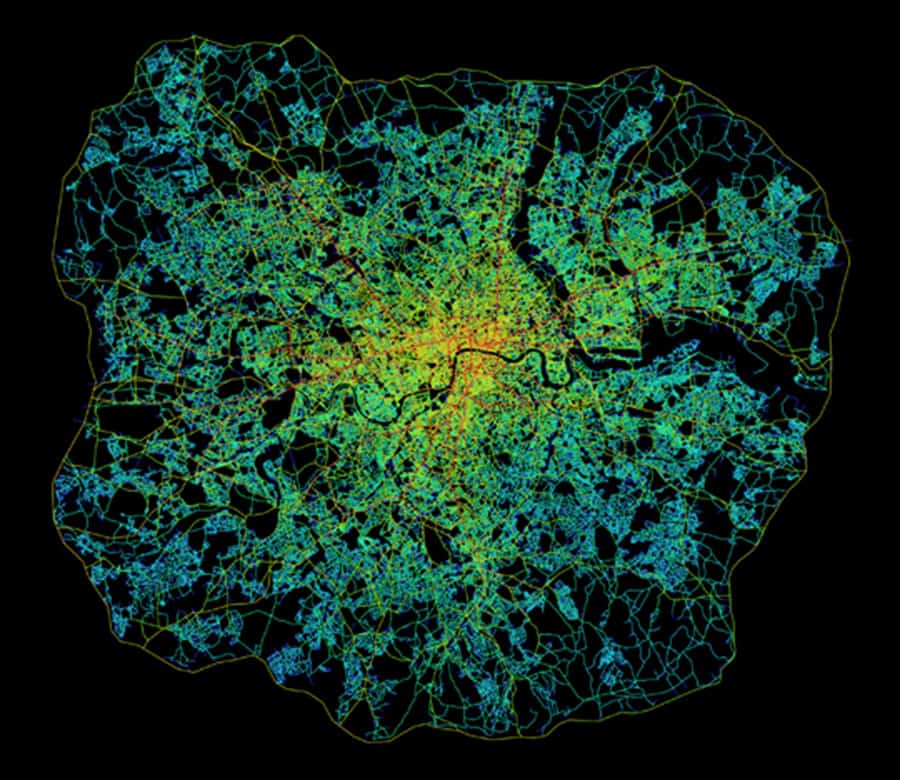

This is because urban space tends to be linear with streets, boulevards, avenues, and alleys but with only occasional (in relative terms) convex elements such as squares and public open space (Hillier, 2005). This can been seen most clearly in axial map of Greater London within the M25 (see below). The axial map represents the most optimal line of sight passing through every accessible space in the London street network until accounting for all accessible spaces and, then, measuring and graphically representing the spatial configuration of that network in terms of topological depth (see

This is because urban space tends to be linear with streets, boulevards, avenues, and alleys but with only occasional (in relative terms) convex elements such as squares and public open space (Hillier, 2005). This can been seen most clearly in axial map of Greater London within the M25 (see below). The axial map represents the most optimal line of sight passing through every accessible space in the London street network until accounting for all accessible spaces and, then, measuring and graphically representing the spatial configuration of that network in terms of topological depth (see

This means it is the design of the urban pattern in the shape of its grid that most matters. In this sense, natural movement is akin to a background effect of the urban grid since most movement in space will tend to be through-movement that is passing through a space on its way to somewhere else in the urban grid. The distribution of activities and land uses then has the potential to further intensify, or detract from, the background effects of natural movement (Hillier, 1996; Hillier and Vaughan, 2007).

This means it is the design of the urban pattern in the shape of its grid that most matters. In this sense, natural movement is akin to a background effect of the urban grid since most movement in space will tend to be through-movement that is passing through a space on its way to somewhere else in the urban grid. The distribution of activities and land uses then has the potential to further intensify, or detract from, the background effects of natural movement (Hillier, 1996; Hillier and Vaughan, 2007).

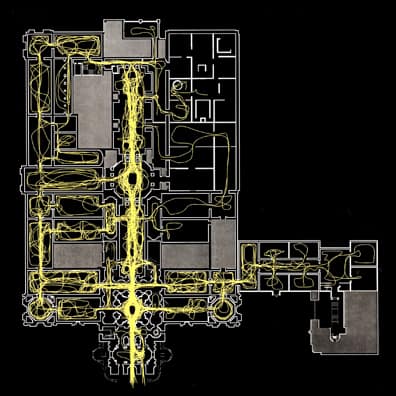

Later methodological developments in space syntax allow for the measurement of the configurational relationship of all visual fields from a gridded set of points (or point isovists) to all others in a built environment. These form a matrix of visual fields where some are more strategic than others for understanding the spatial network as a whole (see the space syntax model of visual fields in the Tate Gallery, Millbank in

Later methodological developments in space syntax allow for the measurement of the configurational relationship of all visual fields from a gridded set of points (or point isovists) to all others in a built environment. These form a matrix of visual fields where some are more strategic than others for understanding the spatial network as a whole (see the space syntax model of visual fields in the Tate Gallery, Millbank in