“Day is done but there’s no job to be found in Salt Lake City,

Room’s cold no one to hold so I’ll just walk around,

And think of all the times that she said that she loved me,

But that’s just a mem’ry in Salt Lake City.”

— Salt Lake City, Hank Williams, Jr.

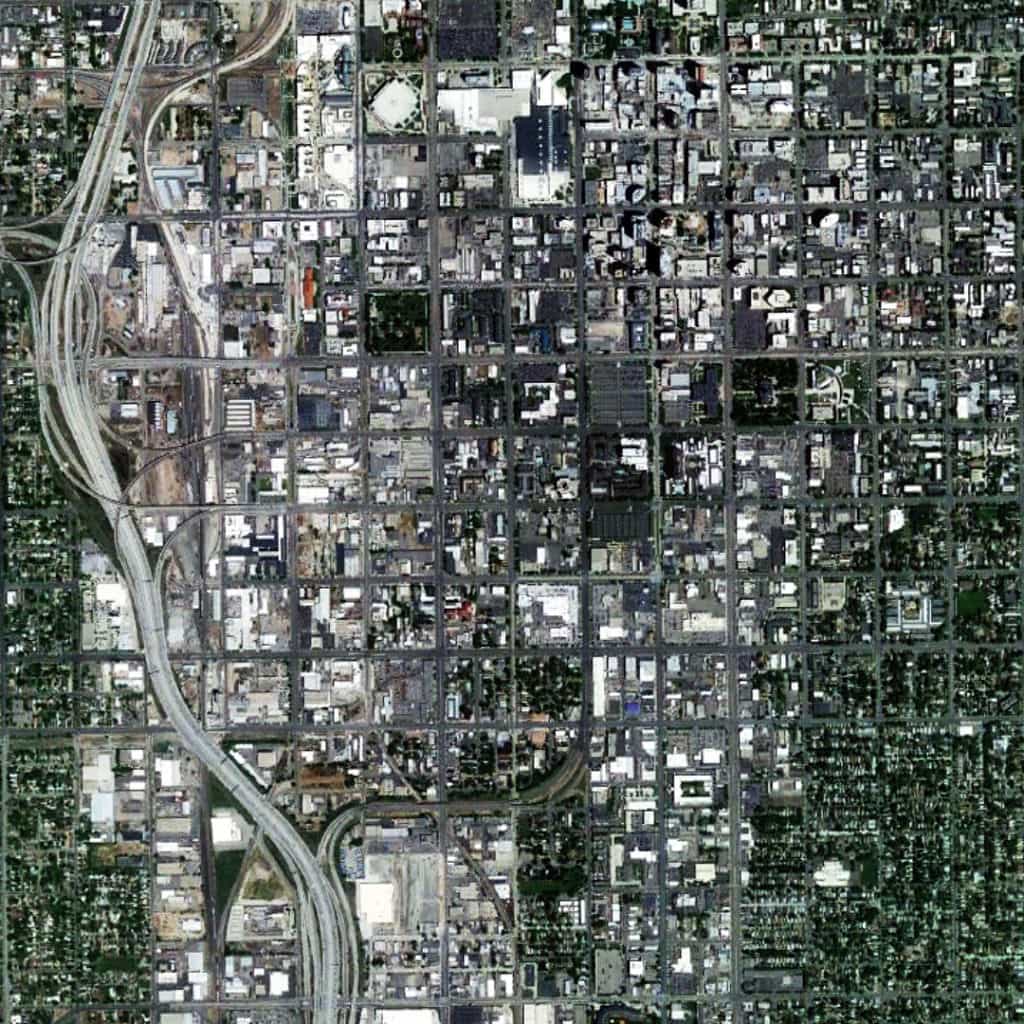

Urban Patterns | Salt Lake City, Utah USA

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

Originally posted on May 17, 2013

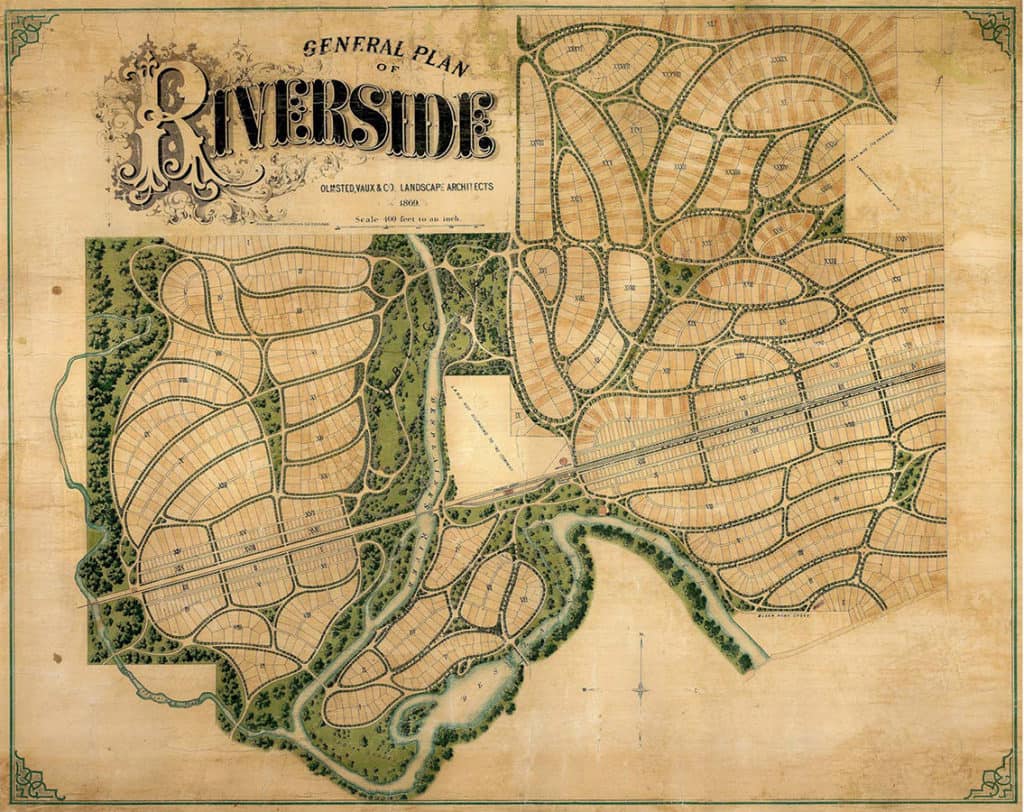

This week we are looking at the urban pattern of Salt Lake City, Utah USA in honor of where CNU21 (21st Congress for New Urbanism Conference) will be (was) held May 29-June 1, 2013. Salt Lake City was founded in 1847 in what was still Mexican Territory by Brigham Young, Isaac Morley, George Washington Bradley and several other Mormon followers, who extensively irrigated and cultivated the arid valley. Brigham Young claimed to have seen the area in a vision prior to their arrival. Due to its proximity to the Great Salt Lake, the city was originally named “Great Salt Lake City” but the word “great” was dropped from the official name in 1868. Although Salt Lake City is still home to the headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), less than half of its population are Mormons today (Source: Wikipedia).

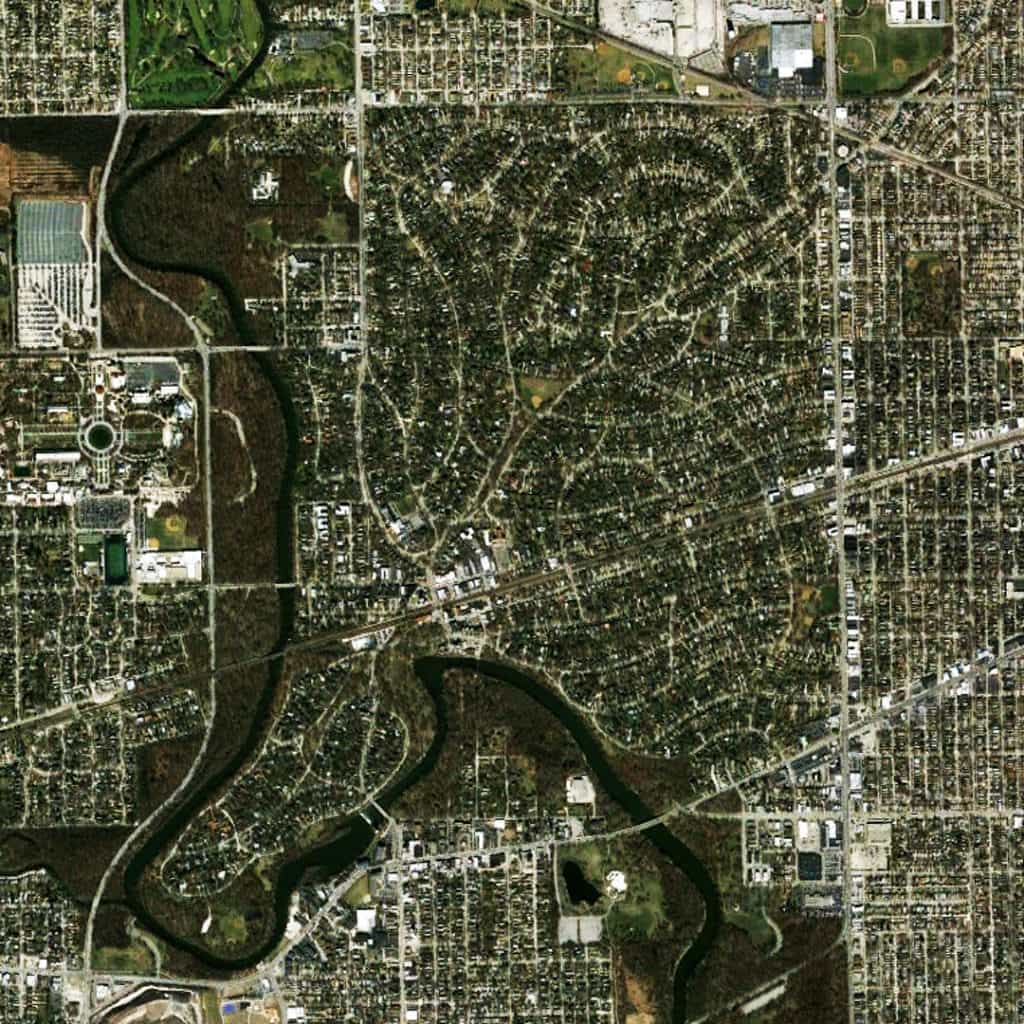

The urban pattern of Salt Lake City is extremely interesting for an American city due to the emphasis on square blocks. This is atypical for most pre-20th century American cities, which usually and rapidly developed using a well-defined land speculation process. 19th-century American land speculators tended to elongate urban blocks into a rectangular shape (for example, in Denver and Chicago) to maximize the number of available lots for sale and, hence, their profits. However, Salt Lake City was founded by the Mormons, who were (initially) more interested in the social order of their settlement as imprinted in its physical pattern than personal economic gain. So, they laid out the settlement using a regular grid composed of square blocks. Salt Lake City is a perfect illustration of Poor Richard’s maxim that, “Compact block sizes are about community. Ample block sizes are about profit.”

(Updated: May 18, 2017)

Urban Patterns is a series of posts from The Outlaw Urbanist presenting interesting examples of terrestrial patterns shaped by human intervention in the urban landscape over time.