BOOK REVIEW | Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism by Benjamin Ross

BOOK REVIEW | Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism by Benjamin Ross

Review by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

The first half of Benjamin Ross’ Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism (2014, Oxford University Press) is a majestic masterpiece of objective, clear, and concise diagnosis about the political, economic, and social origins of suburban sprawl in the United States with particular emphasis on the legal and regulatory pillars (restrictive covenants and exclusionary zoning ) perpetuating suburban sprawl to this day. It is required reading for anyone interested in the seemingly intractable problems of suburban sprawl we face today in building a more sustainable future for our cities. Chapters 1-10 (first 138 pages) of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism warrants a five-star plus rating alone.

However, Ross’ book becomes more problematic with the transition from diagnosis to prescription, beginning with an abrupt change in tone in Chapter 11. This chapter titled “Backlash from the Right” is, in particular, so politically strident that it reads as if the staff of Harry Reid’s Senate office wrote the text (the political left’s favorite boogeymen, the Koch Brothers, are even mentioned); or perhaps, the text of this chapter sprouted wholesale like Athena from the “vast right wing conspiracy” imaginings of Hillary Clinton’s head. This is unfortunate. In the second half of the book, Ross starts to squander most – if not all – of the trust he earned with readers during the exemplary first half of the book. It is doubly unfortunate because: first, it is done solely in the service of political dogma as Ross unconvincingly attempts to co-opt Smart Growth as a wedge issue for the political left in the United States; and second, it unnecessarily alienates ‘natural’ allies on the conservative and libertarian right sympathetic to Ross’ arguments for strong cities and good urbanism.

In the process, Ross tends to ignore or paper over blatant contradictions littering the philosophy of the political left in the United States when it comes to cities. Of course, this is a common Baby Boomer leftist tactic of absolving their generation for the collective disaster they’ve helped to create over the last half-century by confusing ideology for argument (and hoping no one will notice there’s a difference). For example, if you want to see what the policies of the political left look like after three-quarters of a century of dominance, then look no further than East St. Louis, Illinois. What has happened to that once vibrant city is absolutely criminal; literally so since several state and city Democratic officials and staffers have been sent to jail for corruption for decades.

During the second half of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, Ross also promotes the classic Smart Growth fallacy that public rail transit is the ‘magic bullet’ for reviving our cities. Indeed, public rail transit is important but too often Ross – like many others – comes across as unconsciously applying Harris and Ullman’s multi-nuclei model of city growth, which conveniently holds almost any function (in this case, rail stations/lines) can be randomly inserted almost anywhere in the fabric of a city without repercussions as long as land uses are ‘compatible.’ Of course, this is the ex post facto theoretical underpinning for the very ideas of Euclidean zoning and the common umbrella providing regulatory cover for all sorts of disastrous decisions in the name of “economic development.”

During the second half of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism, Ross also promotes the classic Smart Growth fallacy that public rail transit is the ‘magic bullet’ for reviving our cities. Indeed, public rail transit is important but too often Ross – like many others – comes across as unconsciously applying Harris and Ullman’s multi-nuclei model of city growth, which conveniently holds almost any function (in this case, rail stations/lines) can be randomly inserted almost anywhere in the fabric of a city without repercussions as long as land uses are ‘compatible.’ Of course, this is the ex post facto theoretical underpinning for the very ideas of Euclidean zoning and the common umbrella providing regulatory cover for all sorts of disastrous decisions in the name of “economic development.”

This is a potentially dangerous self-delusion shared by many in the Smart Growth movement. For example, what Ross attributes as the cause for the failure of some rail stations (lack of walkable, urban development around these stations due to the over-provision of space for ‘park and ride’ lots in catering to the automobile) is often really a symptom. The real disease is these stations were put in the wrong location in the first place due to local opposition, regulatory convenience, and/or political cowardice (i.e. that’s where the land was available). There is an inherent danger in approaching pubic rail transit as a cure-all panacea for the city’s problems. If our leaders, planners, and engineers take shortcuts in the planning, design, and locating of rail lines/stations, then we leave the fate of our cities to happenstance. It is far too important of an issue to approach in such a cavalier manner, as some Smart Growth advocates appear so inclined.

In a general sense, this is not really different from the arguments made in Dead End but, specifically, it is an important distinction that is glossed over or not properly understood when drilling down into the crucial details of Ross’ prescriptions. That being said, there are some interesting tidbits and ideas in the ‘prescription phase’ of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism. However, the reader has to be extremely careful about filtering out Ross’ political agenda from the more important morsels. For example, Ross correctly points out Americans’ disdain for buses is rooted in social status. However, he fails to point out – or perhaps even realize – that this peculiar American attitude is indoctrinated from childhood due to the expansive busing of kids to school in the United States (e.g.. only the poor and unpopular kids take the bus). In order to change this attitude, you have to radically change public education policies, something contrary to the invested interests of the political left. In fact, Ross has very little to say about schools, which seems like an odd oversight.

Too often, Ross’s prescription for building coalitions comes across as the same, old political activism of the counter-culture Baby Boomers that doesn’t really rise above the level of gathering everyone around the campfire and singing “Kumbaya, My Lord” (absent the “My Lord” part in the interests of political correctness). In the end, this suggests Ross has a well-grounded understanding about the historical, political and social impact of legal and regulatory instruments at work in our cities (exemplified by the first half of this book) but only a superficial idea about the design and function of cities and movement networks (including streets and rail) as witnessed by the lackluster second half, which is barely worth a two-star rating. Because of these strengths and weaknesses, Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism is a four-star book in its entirety but you might be better served by reading the first half of the book, ignoring the second half, and having the courage to chart your own path in the fight for better cities.

Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism

Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism

by Benjamin Ross

Hardcover, English, 256 pages

New York: Oxford University Press (May 2, 2014)

ISBN-10: 0199360146

ISBN-13: 978-0199360147

Available for purchase from Amazon here.

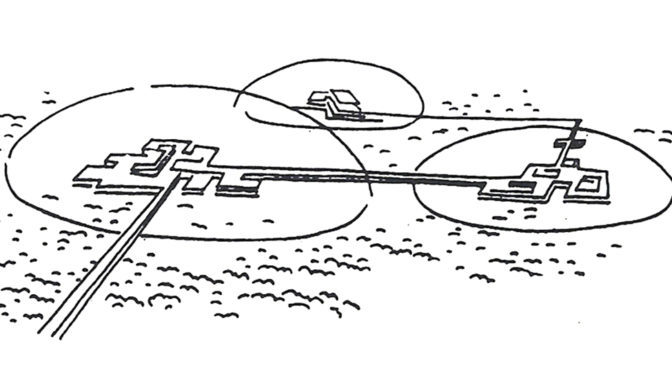

Of course, the key difference is the authors’ explicitly state the failure of these ideas to “reach their full potential” in Western societies is due to the corrupting influence of capitalism as a political and economic system. This is a conceit that has been badly exposed with time. If anything, capitalism more ruthlessly exploited the economic potentials of Modern ideas by taking them to their logical and, ultimately, extreme conclusion; probably more so than even most devoted CIAM architect ever imagined. The real danger about The Ideal Communist City is that younger readers (Millennials and generations thereafter) without any first-hand experience of the Cold War might make the mistake of thinking they are reading something original and entirely different because it’s wearing Soviet-era clothing. However, it is the same, tired planning paradigm we have been hearing about and (unfortunately) living with over the last 80+ years. To be fair, another key difference in this book is the desire of Soviet-era planners to adopt a model that segregates land uses from one another while still actively promoting manufacturing, mass production, and industrialization. Younger readers might also think this represents a somewhat unique perspective from the point of view of architecture and planning. However, it is really only evidence of Soviet preoccupation – even obsession – with Western societies’ manufacturing prowess at the time. In this sense, Soviet failure to compete with the success of Western capitalistic societies contradicted the ‘means of production’ arguments underpinning Karl Marx and Frederick Engel’s The Communist Manifesto and Marx’s Das Capital; that is, direct evidence that communism was a flawed political and economic system based on totalitarianism masquerading as a false ideology

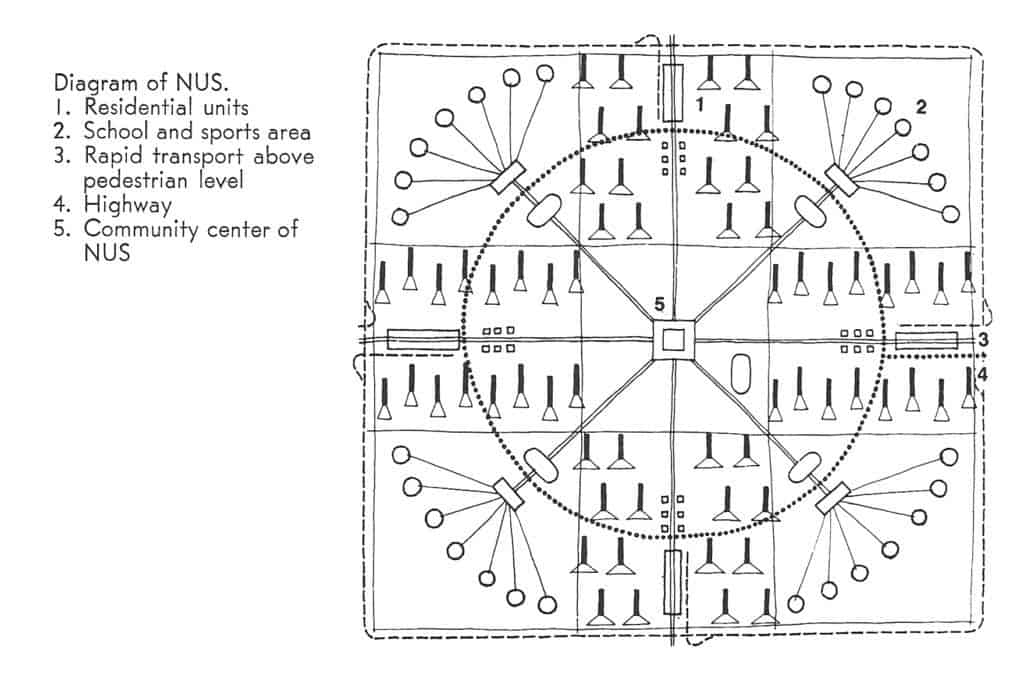

Of course, the key difference is the authors’ explicitly state the failure of these ideas to “reach their full potential” in Western societies is due to the corrupting influence of capitalism as a political and economic system. This is a conceit that has been badly exposed with time. If anything, capitalism more ruthlessly exploited the economic potentials of Modern ideas by taking them to their logical and, ultimately, extreme conclusion; probably more so than even most devoted CIAM architect ever imagined. The real danger about The Ideal Communist City is that younger readers (Millennials and generations thereafter) without any first-hand experience of the Cold War might make the mistake of thinking they are reading something original and entirely different because it’s wearing Soviet-era clothing. However, it is the same, tired planning paradigm we have been hearing about and (unfortunately) living with over the last 80+ years. To be fair, another key difference in this book is the desire of Soviet-era planners to adopt a model that segregates land uses from one another while still actively promoting manufacturing, mass production, and industrialization. Younger readers might also think this represents a somewhat unique perspective from the point of view of architecture and planning. However, it is really only evidence of Soviet preoccupation – even obsession – with Western societies’ manufacturing prowess at the time. In this sense, Soviet failure to compete with the success of Western capitalistic societies contradicted the ‘means of production’ arguments underpinning Karl Marx and Frederick Engel’s The Communist Manifesto and Marx’s Das Capital; that is, direct evidence that communism was a flawed political and economic system based on totalitarianism masquerading as a false ideology Having said all that, The Ideal Communist City is an important historical document that anyone interested in town planning should probably be exposed at some point, as long as the book is placed within its proper context for readers, especially post-Cold War ones. There are, in fact, relatively few flights of fancy in this book; the most amusing one being the common idea in science fiction that cities will eventually be covered by climate-controlled plastic domes (see Featured Image of this post at the top). The authors’ statistical projections of urban populations are way off, hilariously so. Early in the book, the authors project that 75% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by the year 2000 when it fact we only passed the 50% threshold in the last decade (due to the corrupting influence of capitalism, no doubt). The model of the NUS stretches believability despite the authors’ best – though somewhat halfhearted – efforts to address accommodating population growth during the transition period between one NUS being occupied and the next one being constructed. This is because these Soviet-era planners ultimately have a static view of the city. In hindsight, one might fairly argue the communist NUS model has already been better implemented and realized in cities such as Milton Keynes in England, the Pilot Plan of Brasilia in Brazil, or perhaps even some areas of America Suburbia, despite the problematic nature of such places as extensively discussed elsewhere in the literature. In the end, the Ideal Communist City is perhaps best at asking some interesting questions about cities but the answers provided are all too familiar and depressing to seriously contemplate. As Christopher Alexander famously said, “a city is not a tree.” It seems the same is as true for communist cities as it ever was for capitalistic ones. In the end, human nature is always more pervasive than any political ideology.

Having said all that, The Ideal Communist City is an important historical document that anyone interested in town planning should probably be exposed at some point, as long as the book is placed within its proper context for readers, especially post-Cold War ones. There are, in fact, relatively few flights of fancy in this book; the most amusing one being the common idea in science fiction that cities will eventually be covered by climate-controlled plastic domes (see Featured Image of this post at the top). The authors’ statistical projections of urban populations are way off, hilariously so. Early in the book, the authors project that 75% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by the year 2000 when it fact we only passed the 50% threshold in the last decade (due to the corrupting influence of capitalism, no doubt). The model of the NUS stretches believability despite the authors’ best – though somewhat halfhearted – efforts to address accommodating population growth during the transition period between one NUS being occupied and the next one being constructed. This is because these Soviet-era planners ultimately have a static view of the city. In hindsight, one might fairly argue the communist NUS model has already been better implemented and realized in cities such as Milton Keynes in England, the Pilot Plan of Brasilia in Brazil, or perhaps even some areas of America Suburbia, despite the problematic nature of such places as extensively discussed elsewhere in the literature. In the end, the Ideal Communist City is perhaps best at asking some interesting questions about cities but the answers provided are all too familiar and depressing to seriously contemplate. As Christopher Alexander famously said, “a city is not a tree.” It seems the same is as true for communist cities as it ever was for capitalistic ones. In the end, human nature is always more pervasive than any political ideology.

Planning Naked | April 2016

Planning Naked | April 2016

7. “Flipping the Strip” by Randall Arendt for the Planning Practice section (pp. 32-35) is, by far, the most important article in this month’s issue. Naturally, it is an editorial/layout nightmare as the editors of Planning Magazine almost seem to be going out of their way to undercut the content, which transforms a relatively straightforward, clear, and concise argument into a confusing presentation for the readers to follow. Mr. Arendt should be upset about how his content was butchered by the editors.

7. “Flipping the Strip” by Randall Arendt for the Planning Practice section (pp. 32-35) is, by far, the most important article in this month’s issue. Naturally, it is an editorial/layout nightmare as the editors of Planning Magazine almost seem to be going out of their way to undercut the content, which transforms a relatively straightforward, clear, and concise argument into a confusing presentation for the readers to follow. Mr. Arendt should be upset about how his content was butchered by the editors.

Planning Naked | March 2016

Planning Naked | March 2016 That’s not to say there aren’t good, interesting items in here (there are) but it’s a chore to sort through the mess and the constant “take (insert ‘community name/plan’ here)” asides are irritating in the extreme. It’s like someone composed a checklist, which can be re-constructed based on these paragraph ‘take this example’ asides. Let me try to help the readers: pp. 14-19 is ‘buzzword’ fluff that reads like a committee of marketing agencies wrote it (ignore it unless you find yourself in need of action verbs); pp. 20-24 (to the first 2 paragraphs) is outstanding because it demonstrates the re-emergence of design (e.g. form-based codes, etc.) as the real driver of new approaches to comprehensive plans and, in typical APA fashion, the awkward structure is designed to subvert the real story in order to re-assert (or, perhaps, soften the blow to) traditional planning approaches in the post-war period; the rest of the content (pp. 24-31) is mostly more planning fluff and buzzwords except for isolated excerpts here and there about PlanLafayette.

That’s not to say there aren’t good, interesting items in here (there are) but it’s a chore to sort through the mess and the constant “take (insert ‘community name/plan’ here)” asides are irritating in the extreme. It’s like someone composed a checklist, which can be re-constructed based on these paragraph ‘take this example’ asides. Let me try to help the readers: pp. 14-19 is ‘buzzword’ fluff that reads like a committee of marketing agencies wrote it (ignore it unless you find yourself in need of action verbs); pp. 20-24 (to the first 2 paragraphs) is outstanding because it demonstrates the re-emergence of design (e.g. form-based codes, etc.) as the real driver of new approaches to comprehensive plans and, in typical APA fashion, the awkward structure is designed to subvert the real story in order to re-assert (or, perhaps, soften the blow to) traditional planning approaches in the post-war period; the rest of the content (pp. 24-31) is mostly more planning fluff and buzzwords except for isolated excerpts here and there about PlanLafayette.

Planning Naked | February 2016

Planning Naked | February 2016 “A Transportation Bill, At Last” by Jon Davis (pp. 8-9) is combines two things that a lot of planners love the most in this world: acronyms and money. Here’s the long and short of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act… oh, a cool acronym… that must mean it’s important because it’s fast!): for every $1 spent on the automobile (e.g. roads), the US Government is spending 0.24¢ on buses and 0.04¢ on passenger rail. It must be great to be a Washington lobbyist for the ‘automobile cartels’. To quote a song from the 1977 Disney film, Pete’s Dragon, it’s “money, money, money by the pound!” “He that is of the opinion money will do everything may well be suspected of doing everything for money.” – Benjamin Franklin

“A Transportation Bill, At Last” by Jon Davis (pp. 8-9) is combines two things that a lot of planners love the most in this world: acronyms and money. Here’s the long and short of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act… oh, a cool acronym… that must mean it’s important because it’s fast!): for every $1 spent on the automobile (e.g. roads), the US Government is spending 0.24¢ on buses and 0.04¢ on passenger rail. It must be great to be a Washington lobbyist for the ‘automobile cartels’. To quote a song from the 1977 Disney film, Pete’s Dragon, it’s “money, money, money by the pound!” “He that is of the opinion money will do everything may well be suspected of doing everything for money.” – Benjamin Franklin

The raising of the eternal bogeyman of NIMBYism in lower property values and higher crime only makes more transparent the self-serving arguments of those opposed to the sharing economy. Let’s fight for the normal, not the abnormal created in 1926 by the U.S Supreme Court.

The raising of the eternal bogeyman of NIMBYism in lower property values and higher crime only makes more transparent the self-serving arguments of those opposed to the sharing economy. Let’s fight for the normal, not the abnormal created in 1926 by the U.S Supreme Court.