A Fanciful City | REVIEW | American Urban Form: A Representative History

A Fanciful City | REVIEW | American Urban Form: A Representative History

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A, The Outlaw Urbanist contributor

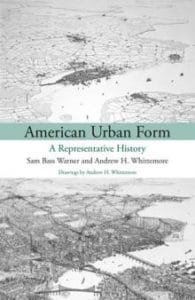

How do you solve a problem like ‘the City’? This is the generic name Sam Bass Warner and Andrew H. Whittemore give to their “hypothetical city” in American Urban Form: A Representative History, available from MIT Press (176 pages; $20.71 on Amazon). Warner and Whittemore’s City is a narrative conglomeration of urban history, for the most part, in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia (New Philaton?) and, therein, lies several dilemmas. The book’s subtitle describes this as “a representative history.” Outside of academia, this is more commonly called historical fiction. It is uncertain the authors’ admirable honesty in admitting this fact (albeit, using academic language) is enough to transform a historical fiction into a substantive scholarly work. All good historical fiction writers conduct research into their subject but tend to not provide footnotes and bibliography (as Bass and Whittemore do). This information is incidental to the goal of telling a good story. So, do we approach American Urban Form as a well-referenced historical fiction or a scholarly work adopting an intriguing (perhaps even innovative) methodological approach to urban history? In the end, it doesn’t really matter.

American Urban Form is more curiosity than ground breaking as a scholarly work. Despite the bold, important title of the book, its publisher, and the authors’ claim “the book is about patterns, the physical patterns or urban form that we can observe in American big cities past and present” and “physical patterns shape and are themselves shaped by” political, social and economic factors, it only discusses urban form incidentally in relation to those factors. In doing so, the authors adopt an a-spatial perspective when discussing the generators of American urban form, which is revealed by their use of the word ‘reflect’ in several instances.  We have to believe this word choice is intentional. In this sense, American Urban Form comfortably sits within the prevailing planning paradigm of the post-war period in the United States (see M. Christine Boyer’s Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning for an excellent and detailed discussion on this topic). Unfortunately, it is also consistent with a recent, unfortunate trend in planning theory to claim to discuss one thing (physical form and space) but substantively reinforce prevailing thought (an a-spatial perspective of the city). Even when American Urban Form does discuss the physical fabric of ‘the City’, it tends to become trapped in discussing architectural styles.

We have to believe this word choice is intentional. In this sense, American Urban Form comfortably sits within the prevailing planning paradigm of the post-war period in the United States (see M. Christine Boyer’s Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning for an excellent and detailed discussion on this topic). Unfortunately, it is also consistent with a recent, unfortunate trend in planning theory to claim to discuss one thing (physical form and space) but substantively reinforce prevailing thought (an a-spatial perspective of the city). Even when American Urban Form does discuss the physical fabric of ‘the City’, it tends to become trapped in discussing architectural styles.

Boston, New York, and Philadelphia seem a stylistic choice for the narrative since they have common temporal and geographical origins, and builds on the foundation of Warner’s previous research into the real history of these cities. It also allows the authors to avoid the emergent effects of 1785 Land Ordinance in generating American urban form (based on the authors’ own timeline, their use of the phrase “Jefferson grid” refers to the regular grid in general, in which case it is more accurately described as the Renaissance grid or even the Spanish grid). In selecting these cities, American Urban Form also reinforces what many see as an ‘East Coast bias’ in urban planning. This is not exactly right. It is actually a ‘Bi-Coastal bias’, which is consistent with a larger cultural bias in the United States. In a real way, there is an ‘axis of planning’ in the United States that stretches from the cabals of MIT to the Ivy League schools to the West Coast (Cal-Berkeley/UCLA) (see “Who Teaches Planning?”, Planitzen, January 14, 2013). By merging these cities together, American Urban Form manages to both undercut and misunderstand the importance of Philadelphia. Philadelphia is more important than New York and way more so than Boston in terms of the American planning tradition. Penn’s 1682 plan for Philadelphia demonstrated the scale of the possible for city planning in the New World.  Namely, American urban form has always been expansive, what Gandelsonas referred to as “the invention of a new scale”, especially in comparison to European models of urbanism. If the authors had taken different cities as their subject (such as Chicago, St. Louis, and New Orleans), then a different (and, perhaps, more common) picture might have emerged in their narrative about the physical form of the American city.

Namely, American urban form has always been expansive, what Gandelsonas referred to as “the invention of a new scale”, especially in comparison to European models of urbanism. If the authors had taken different cities as their subject (such as Chicago, St. Louis, and New Orleans), then a different (and, perhaps, more common) picture might have emerged in their narrative about the physical form of the American city.

This fact reveals the subjectivity lurking at the heart of American Urban Form. The authors’ experiment in representative history fails the most basic test of scientific method because their methodology cannot be objectively repeated to produce similar results for different cities. The results are entirely determined by the subjective choices of those writing the narrative. In this regard, the methodology might be useful as the basis for a student studio project but of little use to anyone outside the classroom. Also, taking the two densest cities in the United States (Boston and New York) as the subject for two-thirds of ‘the City’ allows the authors to craft an overly romantic view (in New Urbanist and Floridian “creative class” terms) of American urban form that does not ring true for the majority of the country. A quick review of Wikipedia’s listing of America’s most dense cities reveals two-thirds are located in the New York and Boston metropolitan regions; though interestingly and importantly, not Philadelphia. It is also interesting the authors’ descriptions of urban form become considerably more assured with the onset of the 20th century, which coincides with the emergence of urban planning as a distinct discipline. Before this, the authors provide as much space to discussing free-range hogs as they do to urban form.  In itself, this is revealing since roughly half of the book is devoted to the first 200 years of ‘the City’ whereas the second half covers approximately the last 115 years. This is unfortunate since important aspects of early urban form are casually mentioned and their generative effects are not explored in detail. Instead, the narrative quickly returns to surer ground. i.e. a pseudo-history of political, social, and economic factors.

In itself, this is revealing since roughly half of the book is devoted to the first 200 years of ‘the City’ whereas the second half covers approximately the last 115 years. This is unfortunate since important aspects of early urban form are casually mentioned and their generative effects are not explored in detail. Instead, the narrative quickly returns to surer ground. i.e. a pseudo-history of political, social, and economic factors.

Does American Urban Form work as historical fiction? Well, not really. The book cannot be given a pass on these grounds either. Disturbingly for academics, this methodology seems to provide the authors with an in-built defense mechanism against criticism and, more importantly, testing of their ideas. Hey, it’s only “a representative history”, meaning, of course, it is a fiction so we have to evaluate the book on these grounds as well. We tend to teach historical fiction (Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Anthony and Cleopatra, and so forth) in literature courses, not history classes, because what is important is not historical accuracy but the use of literary devices in telling a story. American Urban Form fails the most basic literary tests in this regard. There is no characterization, rising action, dramatic climax, or dénouement. It is all conflict. Most of the book reads like an urban horror story where everyone is neatly divided into oppressor (rich white male, capitalist landowners) and the oppressed (everyone else who is not, especially Black Americans, women, and unions). This provides most of the narrative with an oddly Marxist perspective on American urban history. We say ‘oddly’ because it is so unexpected. This fictional urban history of capitalist oppression in ‘the City’ would sit a little too close for comfort (for some) next to the fictional history of capitalism written by Karl Marx in Das Kapital. The authors drop this odd perspective on their imagined history with the onset of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and the leftist radicalism of the 1960s, which, in effect, conveys an apologia for the social conscience and actions of leftist baby boomers. For example, the authors state not once but twice (without explanation) the economic stagnation of the 1970s was caused by the Vietnam War. It will be a surprise to many who thought it was monetary policy, high taxation and excessive regulatory regimes during the Johnson, Nixon, and Carter Administrations as well as out-of-control government spending by a long-held Democratic U.S. Congress (the Reagan Revolution of 1980s does not seem to exist in the imagined world of ‘the City’, except incidentally or negatively).

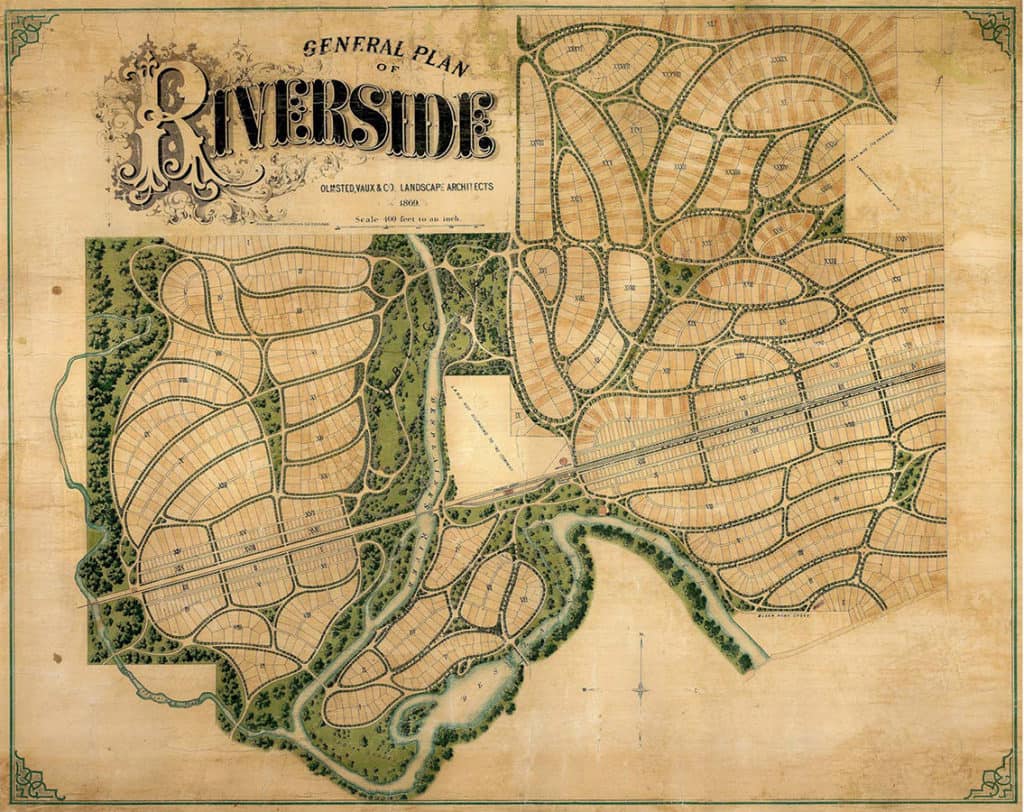

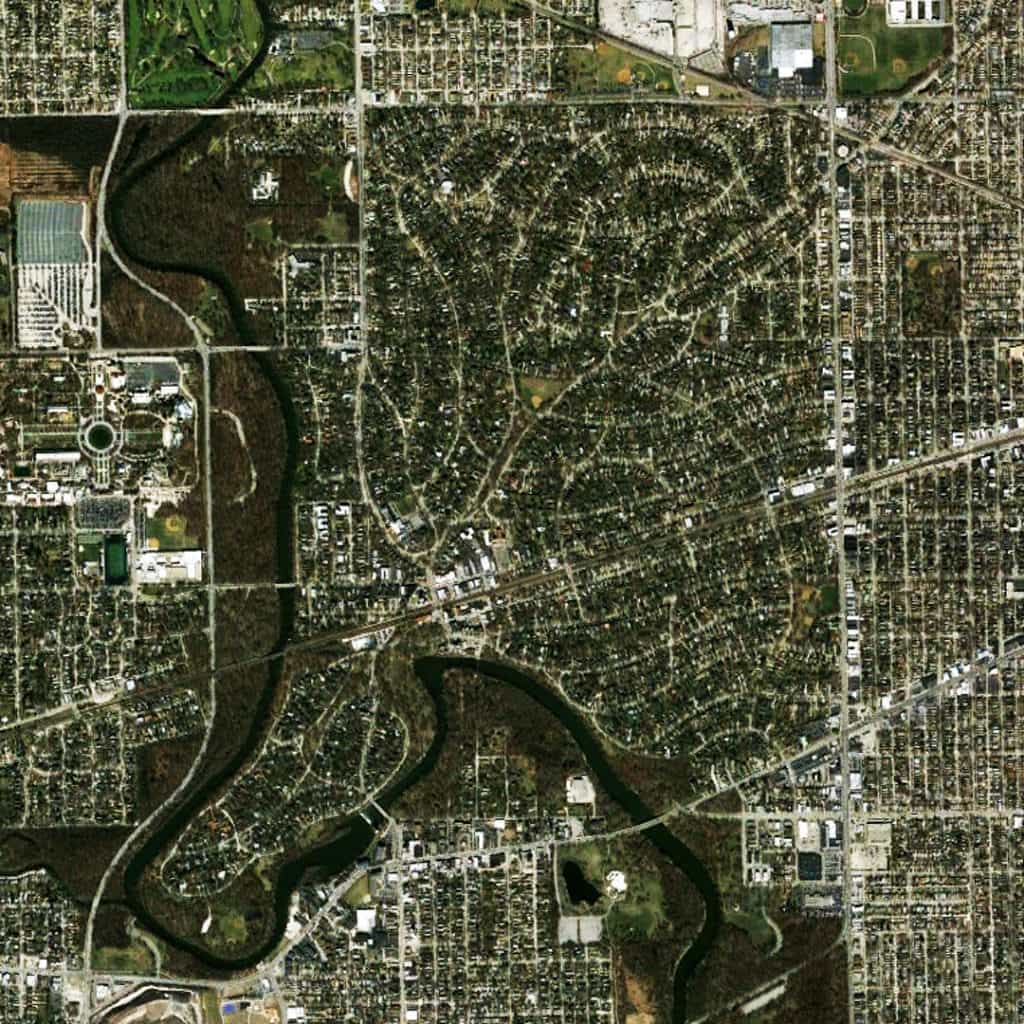

In this sense, American Urban Form represents the worst kind of historical revisionism, indoctrinating leftist wish fulfillment (capitalism is evil, the state is good… and everything that follows on from that view) as a “representative” fact of American urban history. Because of this, it does not even qualify as good historical fiction.  Much like Whittemore’s detailed and pretty bird’s eye views of ‘the City’ in the book (for the most part, vacant of meaning because they are a fiction, too; the one clear-cut exception is his wonderful aerial perspective of ‘dumbbell tenements’ on page 71), American Urban Form remains trapped in a single perspective on its subject. It either ignores, consigns to happenstance, or weaves an elaborate explanation for anything that might contradict or interrupt that perspective. Collectively, the result is a fanciful city of leftist, pseudo-Marxist fallacies. If you are already a member of the choir, you will like American Urban Form: A Representative History because you know the song and can sing along. If not, you will be better served by reading the history of a real city, examining in detail its historical plans and bird’s eye view drawings, and making your own conclusions.

Much like Whittemore’s detailed and pretty bird’s eye views of ‘the City’ in the book (for the most part, vacant of meaning because they are a fiction, too; the one clear-cut exception is his wonderful aerial perspective of ‘dumbbell tenements’ on page 71), American Urban Form remains trapped in a single perspective on its subject. It either ignores, consigns to happenstance, or weaves an elaborate explanation for anything that might contradict or interrupt that perspective. Collectively, the result is a fanciful city of leftist, pseudo-Marxist fallacies. If you are already a member of the choir, you will like American Urban Form: A Representative History because you know the song and can sing along. If not, you will be better served by reading the history of a real city, examining in detail its historical plans and bird’s eye view drawings, and making your own conclusions.

American Urban Form: A Representative History by Sam Bass Warner and Andrew H. Whittemore with Illustrations by Andrew H. Whittemore, 176 pages, MIT Press, is available from MIT Press here and Amazon here in hardcover and Kindle formats. Prices may vary.

American Urban Form: A Representative History by Sam Bass Warner and Andrew H. Whittemore with Illustrations by Andrew H. Whittemore, 176 pages, MIT Press, is available from MIT Press here and Amazon here in hardcover and Kindle formats. Prices may vary.

We have to believe this word choice is intentional. In this sense, American Urban Form comfortably sits within the prevailing planning paradigm of the post-war period in the United States (see M. Christine Boyer’s Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning for an excellent and detailed discussion on this topic). Unfortunately, it is also consistent with a recent, unfortunate trend in planning theory to claim to discuss one thing (physical form and space) but substantively reinforce prevailing thought (an a-spatial perspective of the city). Even when American Urban Form does discuss the physical fabric of ‘the City’, it tends to become trapped in discussing architectural styles.

We have to believe this word choice is intentional. In this sense, American Urban Form comfortably sits within the prevailing planning paradigm of the post-war period in the United States (see M. Christine Boyer’s Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning for an excellent and detailed discussion on this topic). Unfortunately, it is also consistent with a recent, unfortunate trend in planning theory to claim to discuss one thing (physical form and space) but substantively reinforce prevailing thought (an a-spatial perspective of the city). Even when American Urban Form does discuss the physical fabric of ‘the City’, it tends to become trapped in discussing architectural styles. Namely, American urban form has always been expansive, what Gandelsonas referred to as “the invention of a new scale”, especially in comparison to European models of urbanism. If the authors had taken different cities as their subject (such as Chicago, St. Louis, and New Orleans), then a different (and, perhaps, more common) picture might have emerged in their narrative about the physical form of the American city.

Namely, American urban form has always been expansive, what Gandelsonas referred to as “the invention of a new scale”, especially in comparison to European models of urbanism. If the authors had taken different cities as their subject (such as Chicago, St. Louis, and New Orleans), then a different (and, perhaps, more common) picture might have emerged in their narrative about the physical form of the American city. In itself, this is revealing since roughly half of the book is devoted to the first 200 years of ‘the City’ whereas the second half covers approximately the last 115 years. This is unfortunate since important aspects of early urban form are casually mentioned and their generative effects are not explored in detail. Instead, the narrative quickly returns to surer ground. i.e. a pseudo-history of political, social, and economic factors.

In itself, this is revealing since roughly half of the book is devoted to the first 200 years of ‘the City’ whereas the second half covers approximately the last 115 years. This is unfortunate since important aspects of early urban form are casually mentioned and their generative effects are not explored in detail. Instead, the narrative quickly returns to surer ground. i.e. a pseudo-history of political, social, and economic factors. Much like Whittemore’s detailed and pretty bird’s eye views of ‘the City’ in the book (for the most part, vacant of meaning because they are a fiction, too; the one clear-cut exception is his wonderful aerial perspective of ‘dumbbell tenements’ on page 71), American Urban Form remains trapped in a single perspective on its subject. It either ignores, consigns to happenstance, or weaves an elaborate explanation for anything that might contradict or interrupt that perspective. Collectively, the result is a fanciful city of leftist, pseudo-Marxist fallacies. If you are already a member of the choir, you will like American Urban Form: A Representative History because you know the song and can sing along. If not, you will be better served by reading the history of a real city, examining in detail its historical plans and bird’s eye view drawings, and making your own conclusions.

Much like Whittemore’s detailed and pretty bird’s eye views of ‘the City’ in the book (for the most part, vacant of meaning because they are a fiction, too; the one clear-cut exception is his wonderful aerial perspective of ‘dumbbell tenements’ on page 71), American Urban Form remains trapped in a single perspective on its subject. It either ignores, consigns to happenstance, or weaves an elaborate explanation for anything that might contradict or interrupt that perspective. Collectively, the result is a fanciful city of leftist, pseudo-Marxist fallacies. If you are already a member of the choir, you will like American Urban Form: A Representative History because you know the song and can sing along. If not, you will be better served by reading the history of a real city, examining in detail its historical plans and bird’s eye view drawings, and making your own conclusions.

For example, they generally discuss what they describe as “Landscape Urbanism” without much detail. They are far too kind to reveal what, I suspect, is probably an outright disdain for this approach to serious urban problems. Landscape Urbanism only exists because it is politically expedient and offers policy makers/politicians the appearance of doing something (and feeds the financial coffers of consultants) when, in fact, it is usually a useless solution that avoids the real problem all together. What is really interesting about their historical analysis is where industrial land uses were not located; namely, along the riverfront at the edge of the Woodward plan. This suggests the seeds of Detroit’s urban decline might be traced back to the early 19th century. Large-scale industrial land uses may not have been allowed to develop along the riverfront of the Woodward plan. If the industrial land uses along Davison/Grand had come to be located along the riverfront instead of the northern periphery, Detroit may have been better positioned to manage its transition from an industrial to a post-industrial city, as other cities have accomplished to varying degrees of success.

For example, they generally discuss what they describe as “Landscape Urbanism” without much detail. They are far too kind to reveal what, I suspect, is probably an outright disdain for this approach to serious urban problems. Landscape Urbanism only exists because it is politically expedient and offers policy makers/politicians the appearance of doing something (and feeds the financial coffers of consultants) when, in fact, it is usually a useless solution that avoids the real problem all together. What is really interesting about their historical analysis is where industrial land uses were not located; namely, along the riverfront at the edge of the Woodward plan. This suggests the seeds of Detroit’s urban decline might be traced back to the early 19th century. Large-scale industrial land uses may not have been allowed to develop along the riverfront of the Woodward plan. If the industrial land uses along Davison/Grand had come to be located along the riverfront instead of the northern periphery, Detroit may have been better positioned to manage its transition from an industrial to a post-industrial city, as other cities have accomplished to varying degrees of success.