EDITOR’S NOTE: This is a satire of the article “The Geography of Hate” by Richard Florida about ‘hate’ groups published in The Atlantic on May 11, 2011 and recently re-tweeted by Florida on June 26, 2016 in the aftermath of the Brexit results to leave the European Union. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary’s simple definition of hate is “a very strong feeling of dislike” so a ‘feeling’ (the overall quality of one’s awareness or thought) is being monitored and mapped in the original article.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THOUGHT POLICING

Goodthink concentrates in certain regions, which correlates with secular religion, Obama votes, and ‘self-identified’ elitism

Goodthink (“orthodox thought of the political left”) abounds in our glorious nation, comrades! However, there are still pockets of crimethink (“orthodox thought of the political right”) to be eradicated. We have much to fear from crimethink. And not just from individuals suffering from the insanity of ownlife (“free will”). All citizens must participate in crimestop (“ridding themselves of unwanted thoughts interfering with the ideology of the political left”).

Since 2000, the amount of crimethink has climbed more than 5,000 percent, according to the Ministry of Truth. This rise has been fueled, as all citizens graced with goodthink know, by ignorance, racism, xenophobia, and fascism. Most crimethink merely espouses violent theories against the goodthink; some of them are stock-piling weapons and actively planning attacks against our glorious state.

Since 2000, the amount of crimethink has climbed more than 5,000 percent, according to the Ministry of Truth. This rise has been fueled, as all citizens graced with goodthink know, by ignorance, racism, xenophobia, and fascism. Most crimethink merely espouses violent theories against the goodthink; some of them are stock-piling weapons and actively planning attacks against our glorious state.

But not all people and places goodthink equally; some regions of the United States – at least within some sector of their populations – are a virtual artsem (“artifical insemination”) of goodthink. What is the geography of goodthink and crimethink? Why are some regions more susceptible to one or the other?

The Ministry of Truth maintains a detailed database of crimethink, culled from the prolefeed (“steady stream of mindless entertainment to distract and occupy the masses”). The Ministry defines crimethink as “beliefs or practices that attack or malign goodthink people, typically for their immutable characteristics.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: “immutable characteristics” means that any speech advocating religious persecution does not qualify as crimethink unless, of course, Christians are the subject of that persecution, which is goodthink. For example, ISIS beheading Christians does not qualify for categorization because the executioner may convert (i.e. mutable) to the crimethink of Christianity on the road to Damascus at some unknown date in the future.

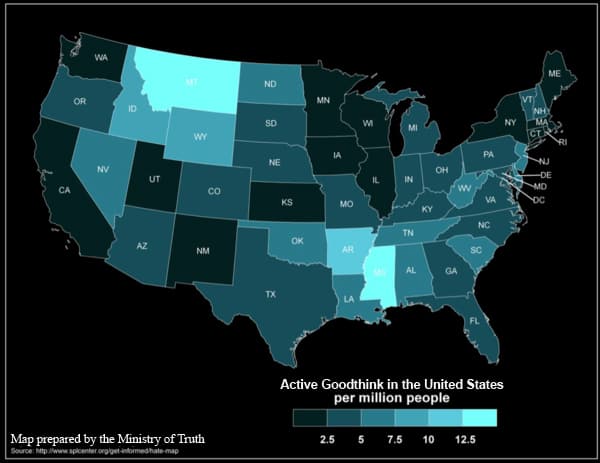

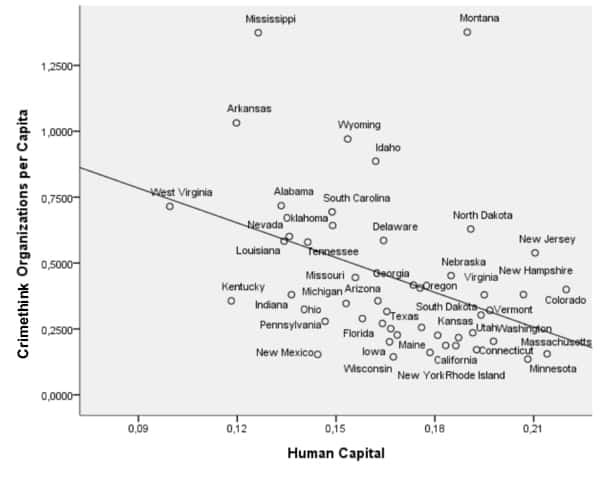

The map below, created by the Ministry of Truth, graphically presents the geography of goodthink in the United States. Based on the number of goodthink groups per one million people across the U.S. states, it reveals a distinctive pattern, which dictates the amount of thinkpol (“thought policing”) required of all goodthinking citizens in their communities.

Goodthink is most highly concentrated in the broader regions associated with New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, concentrated in the Northeast, Great Lakes, and the West Coast. Two states have by far the largest concentration of crimethink groups – Montana with 13.8 groups per million people, and Mississippi with 13.7 per million. Arkansas (10.3), Wyoming (9.7), and Idaho (8.9) come in a distant third, fourth, and fifth.

Minnesota has the most effective thinkpol with 1.3 crimethink groups per million people, nearly ten times less than the leading state, followed by Wisconsin (1.4), New Mexico (1.5), Massachusetts (1.6), and New York (1.6). Connecticut (1.7), California (1.9), Rhode Island (1.9) all also have effective thinkpol per million people.

But beyond their locations, what other factors are associated with crimethink? With the help of the Ministry of Truth, I looked at the social, political, cultural, economic and demographic factors that might be associated with the geography of crimethink. I also considered a number of key factors that shape America’s geographic divide: Red state/Blue state politics; income and poverty; religion, and economic class. It is important to note that correlation does not imply causation – we are simply looking at associations between variables. It’s also worth pointing out that Montana and Mississippi are fairly extreme outliers, which may skew the results somewhat. Nonetheless, the patterns we discerned were robust and distinctive enough to warrant reporting.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “might be” also means ‘might not.’ “Red state/Blue state politics” means there is an implicit political agenda associated with the article.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “It is important to note that correlation does not imply causation – we are simply looking at associations between variables.” Translation: this entire article is statistical bullshit but the author is hoping all goodthinking readers are stupid enough to draw conclusions, that are, in fact, not supported by objective, rigorous interpretation of the statistical analysis.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Montana and Mississippi are fairly extreme outliers, which may skew the results somewhat.” Possible translation: if Montana and Mississippi are removed from the data set, then the correlations fall apart and this article can’t posted to the prolefeed; not that it should have been in the first place.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “Nonetheless, the patterns we discerned were robust and distinctive enough to warrant reporting.” Translation: reporting doublethink promotes groupthink (the last phrase was coined by the notorious crimethinker, William H. Whyte).

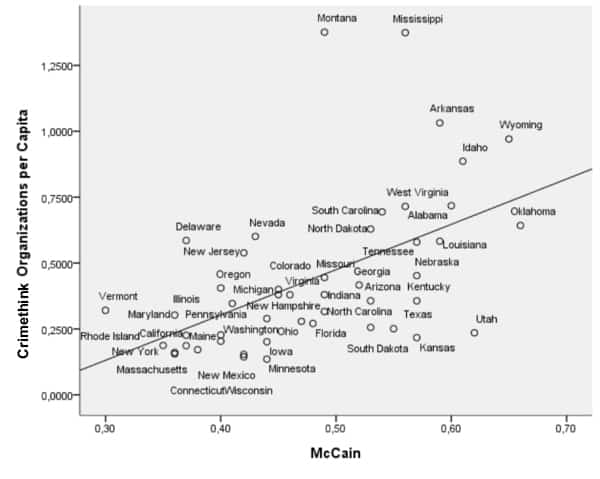

First of all, the geography of crimethink reflects the Red state/Blue state sorting of American politics. Crimethink is positively associated with McCain votes (with a correlation of .52). But we already knew that because it’s a self-evident truth that any state that did not vote for Barack Obama in 2008 is racist; made obvious by their refusal to concede electoral college votes to a man of color.

First of all, the geography of crimethink reflects the Red state/Blue state sorting of American politics. Crimethink is positively associated with McCain votes (with a correlation of .52). But we already knew that because it’s a self-evident truth that any state that did not vote for Barack Obama in 2008 is racist; made obvious by their refusal to concede electoral college votes to a man of color.

EDITOR’S NOTE: It is not self-evident. It is only the starting point of the author’s initial assumption for compiling and analyzing the data set in this manner. However, the author is careful to hide this initial assumption because doubethink pomotes goodthink. The author is also unclear whether these correlations represent the R value or R squared value. The editor’s rule of thumb for R values: unsquared=0.75 or less is most likely a mess.

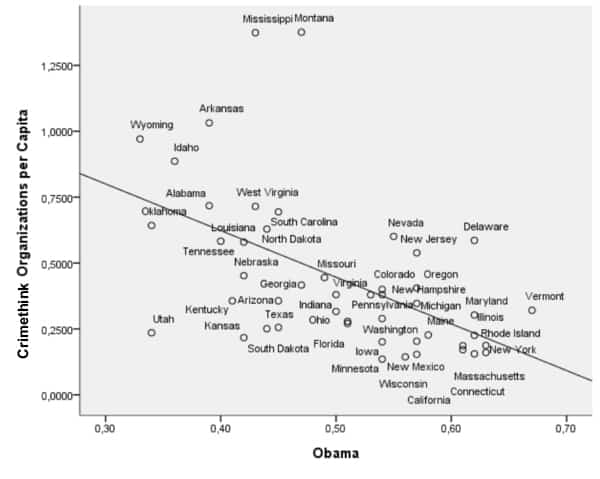

Conversely, goodthink groups voted for our glorious leader.

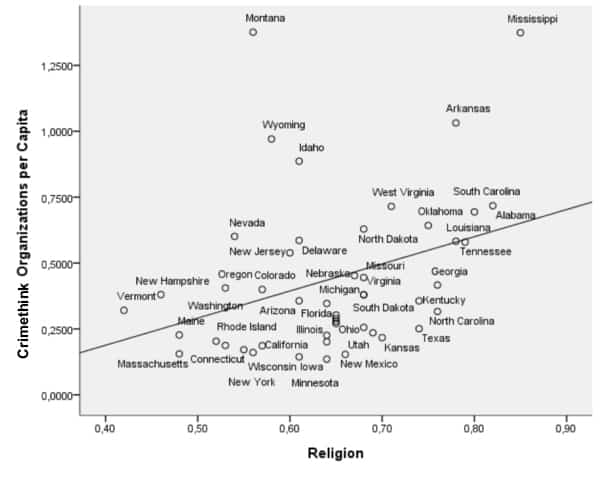

Conversely, goodthink groups voted for our glorious leader.  Goodthink and crimethink also cleaves along religious lines. Ironically, but perhaps not surprisingly, higher concentrations of crimethink are positively associated with states where individuals report that religion plays an important role in their everyday lives (a correlation of .35), indicating the true value of our secular religion.

Goodthink and crimethink also cleaves along religious lines. Ironically, but perhaps not surprisingly, higher concentrations of crimethink are positively associated with states where individuals report that religion plays an important role in their everyday lives (a correlation of .35), indicating the true value of our secular religion.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Whether a R-value or R-squared value, a correlation of 0.35 means bullshit. The geography of crimethink also reflects the sorting of Americans by education and human capital level. Crimethink groups were negatively associated with the percentage of adults holding a college degree (-.41). The geography of goodthink and crimethink also sorts across economic lines. Crimethink is more concentrated in states with higher poverty rates (.39) and those with larger blue-collar working class workforces (.41). Higher income states with greater concentrations of goodthink workers provide a less fertile medium for crimethink. Crimethink was negatively correlated with state income levels (-.36), and the percentage of goodthink workers (-.48).

The geography of crimethink also reflects the sorting of Americans by education and human capital level. Crimethink groups were negatively associated with the percentage of adults holding a college degree (-.41). The geography of goodthink and crimethink also sorts across economic lines. Crimethink is more concentrated in states with higher poverty rates (.39) and those with larger blue-collar working class workforces (.41). Higher income states with greater concentrations of goodthink workers provide a less fertile medium for crimethink. Crimethink was negatively correlated with state income levels (-.36), and the percentage of goodthink workers (-.48).

EDITOR’S NOTE: Most of these correlations appear to be nonsense, all with r-values (?) mostly well below 0.50.

Citizens, if you want to succeed in the United States and earn money, it’s best to adopt goodthink (even if you don’t really mean it, see Arianna Huffington and the Huffington Post). You will be well compensated for groupthink: discipline your ownlife and crimestop yourself!

The geography of crimethink follows the more general sorting of America by politics and ideology, religion, education, income levels, and class. But the presence of crimethink does not necessarily lead to crime. A 2010 study of “Crimethink and Think Crimes” by the Ministry of Love found no empirical connection between the two. Tracing the association between crimethink and think crimes between 2002 and 2006, the Ministry found that while the amount of crimethink grew substantially, the number of think crimes did not – in fact such crimes actually decreased slightly.

The geography of crimethink follows the more general sorting of America by politics and ideology, religion, education, income levels, and class. But the presence of crimethink does not necessarily lead to crime. A 2010 study of “Crimethink and Think Crimes” by the Ministry of Love found no empirical connection between the two. Tracing the association between crimethink and think crimes between 2002 and 2006, the Ministry found that while the amount of crimethink grew substantially, the number of think crimes did not – in fact such crimes actually decreased slightly.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “the presence of crimethink does not necessarily lead to crime… no empirical connection.” Again, this unmasks the author’s article as nothing but goodthink propaganda since there isn’t any relationship between crimethink and actual crimes. The author’s article is, in fact, only promoting thinkpol (“thought policing”).

But the Ministry found a strong connection between crimethink and adverse economic conditions, particularly unemployment and to a lesser extent poverty. This proves citizens should adopt goodthink to avoid the classic crimethink-aggression thesis of the Ministry of Love, which, as its name implies, links aggression to high levels of crimethink. “When people refuse to adopt goodthink, the resulting economic hardship leads to crimethink and frustration,” wrote the deputy assistant undersecretary for the Department of Mutual Masturbation in the Ministry of Love. “They take their frustration out on goodthink citizens.”

Even if crimethink is not directly connected to crime, crimethink arises from the same underlying economic factors that are dividing Americans by class, ideology and politics. Crimethink, like think crimes, are strongly associated with ownlife. The geography of crimethink in America reflects and reinforces the need for more robust thought policing of crimethink.

Remember: Big Brother is watching… and watching goldfish positively correlates with cancer rates so watching goldfish is also crimethink for the greater good of our glorious citizenry. Crimethink clings to bibles and guns!

Planning Naked | June 2016

Planning Naked | June 2016