On Space | The Synthetic City

by Dr. Mark David Major, AICP, CNU-A

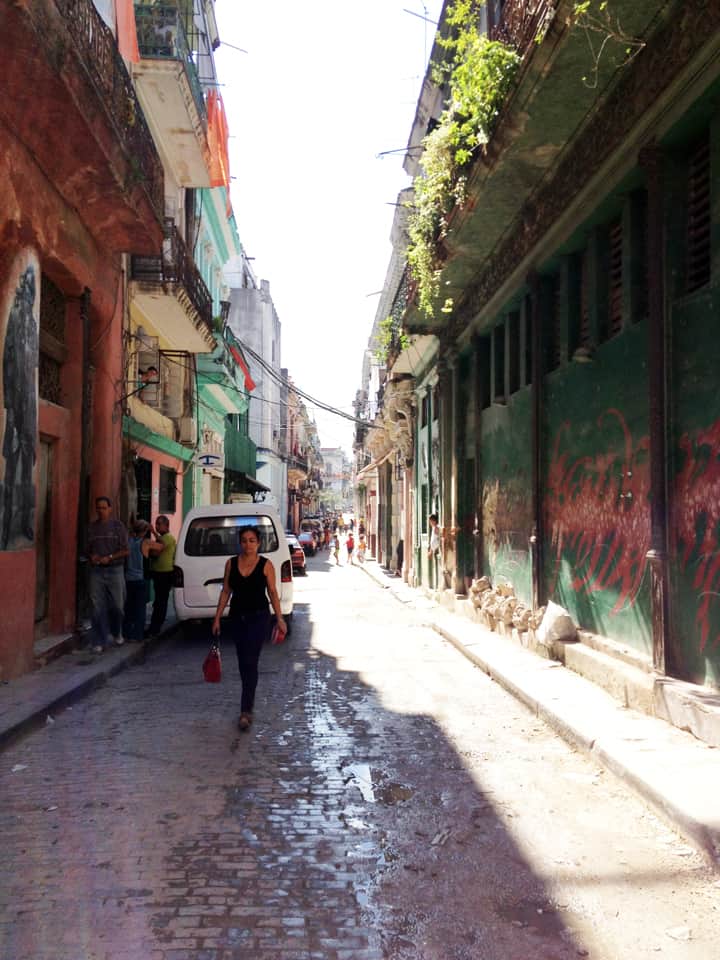

The city is not mere reflection but indefinite inflection and precise infection, where we are cancer and panacea, the never-ending path to its restoration. Its genesis resides in synthesis, its understanding lives in an analysis, and meaning colonizes momentary paralysis into timeless actions and reactions, both great and small, high and low, within and outside of ourselves. The city expands and we grow. The city extends and we go. The city deforms and we change with it. The urban object is a linear extension of ourselves where we might, at last, arrive. The urban object is a horizontal expansion of ourselves, where we might become aware of the infinite possibilities of this life and the next. The elements of the urban object exponentially multiply, two times two equals four, four times four equals sixteen, sixteen times sixteen… and the equation is translated into an answer, which always spells infinity. The urban object offsets and we are inflected within its new, seemingly discordant note, which nonetheless strikes into an innovative harmony that is, at once, frightening in its beauty and comfortable in its unfamiliarity. In that moment, we — by default — privilege the centrality of a place over the oppressive beingness discovered, always renewed in the linearity of the thing itself. We draw an edge where none has a right to exist and, in the process, achieve an unknown quality and quantity of placeness, of definitively being here and not there, of arriving and joining (seemingly) irrevocably with our neighbors. As a result, we unintentionally but – with hopeful care – consolidate the core of its being, adding mass to the heart, fiber to the muscle, which propels stronger and gives new life to the city.

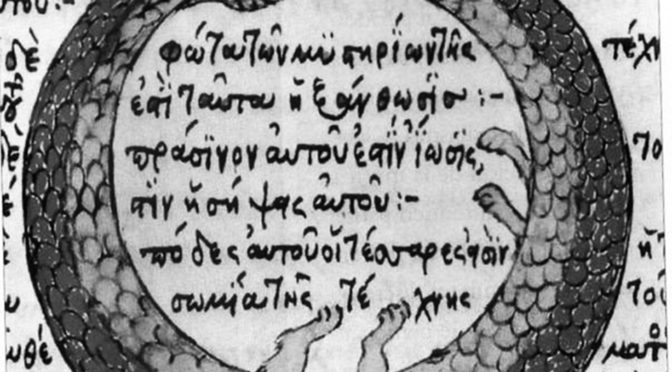

However, with arrogant presumption, we detract from it, and weaker still grows that instrument without which we cannot long endure, robbing the object and its populace of strength. We compensate with a superordinate construct born of artificial assumptions and (sometimes) mistaken imaginations. We impose a hierarchy rather than allow for a structure to naturally emerge, synthesized from the harmony found in the song. False hierarchies arise and confound us, mock us, and dare us with impunity to tear them down. The urban object becomes lost in material things of little substance, of subversive meanings, and we become lost in the process. Where is the Hippocrates of our dreams? Where is the Hippodamus of our desires? Misplaced in time, disoriented in space… and significance. The mistaken dichotomy of our subversive dreaming lacks shape, escapes notice until it is too late, and everyday whispers fetching lies in our ears, offering us comfort where none is ever to be found. The city becomes lost and us with it. We are lost. We vanish into our own reflection, gazing upon the empty space opposite of the mirrored face and wonder, what happened? But the answer to this question is so simple, so elemental: we forgot who we were, who we are and who we could be. We are ashamed and it is insufficient. We must demand more of the urban object and ourselves.

On Space is a regular series of philosophical posts from The Outlaw Urbanist. These short articles (usually about 500 words) are in draft form so ideas, suggestions, thoughts and constructive criticism are welcome.

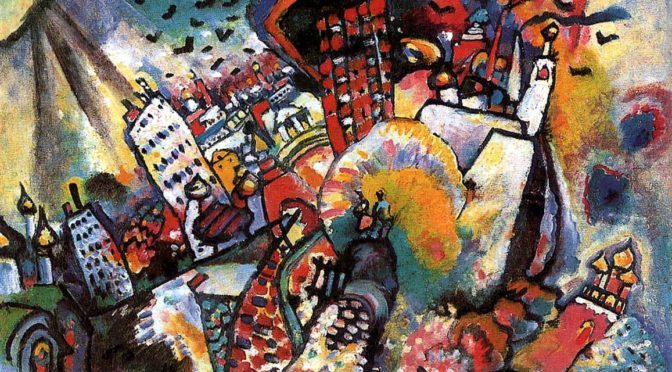

Moscow I contains some of the same romantic fairy-tale qualities of his earlier paintings, fused with dramatic forms and colors. “The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot, which, like a wild tuba, sets all one’s soul vibrating” (Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” 360).

Moscow I contains some of the same romantic fairy-tale qualities of his earlier paintings, fused with dramatic forms and colors. “The sun dissolves the whole of Moscow into a single spot, which, like a wild tuba, sets all one’s soul vibrating” (Kandinsky, “Reminiscences,” 360). About Wassily Kandinsky

About Wassily Kandinsky