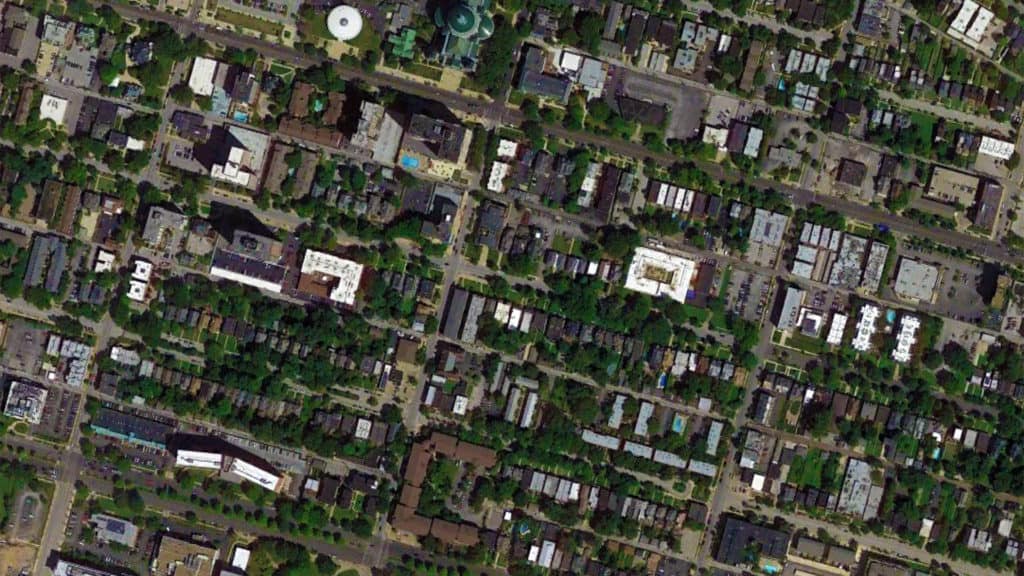

There are few cities in the world more perplexing than Los Angeles. The reasons are many. The Outlaw Urbanist will take a closer look at some of those reasons in a multi-part, photo essay series. Today, we begin with Downtown L.A., which uniquely combines fascination and frustration for any architect, urban designer, and planner with a good conscience.

Downtown L.A. could be incredible urbanism. In fact, it should be incredible urbanism. Instead, it comes across as lazy. Downtown L.A. is alive but not necessarily well. It has ‘good bones’ including some stunning pre-World War II buildings. However, Downtown L.A. desperately needs large doses of TLDC (tender, loving design care), which appears somewhat lacking at the moment.

There were actually a LOT of people in Downtown L.A. on a sunny, warm Sunday afternoon, especially to the south in the Jewelry District. The street level of many buildings has been converted into small, retail units. However, it is haphazardly done for the most part. On one hand, it is good to see the people and retail units. On the other hand, it is such low rent quality that it deters from the innate advantages of the building space above. There are a lot of historic buildings in Downtown L.A. BEGGING for rehabilitation. A few renovations are progressing but not nearly enough. It is deeply frustrating. A lot of the new buildings are design disasters that most often successfully promulgate blank walls in downtown.

Given the history and money surrounding the film industry in Los Angeles, you would think residents and the city would take more care in rehabilitating the plenitude of old historic movie theaters but most often it appears to have been mindlessly done (e.g. Palace Theater above and Los Angeles Theater below) on a ‘cash in’ basis only.

The gorgeous Bradbury Building (below) in Downtown L.A. was designed by Sumner Hunt and designated an architectural landmark in 1977. Its interior and rooftop were the settings for the climatic scenes of Ridley Scott’s science fiction classic Blade Runner (1982).

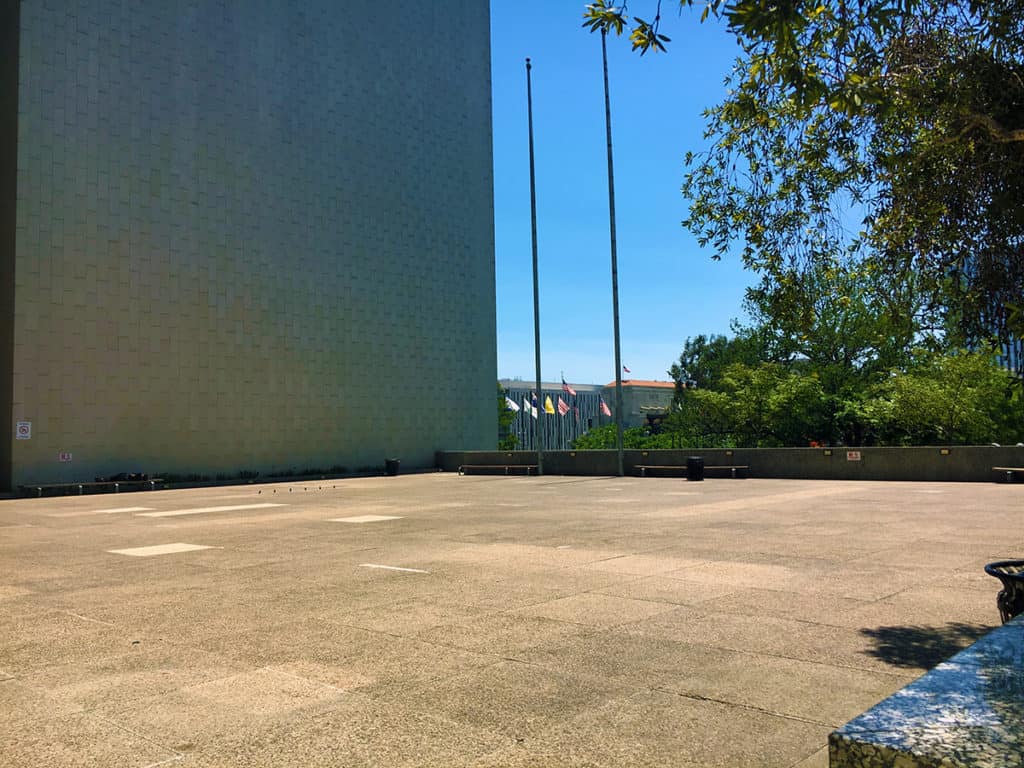

The government sector to the north in Downtown L.A. effectively demonstrates the danger of single-use districts. Whereas the Jewelry District was populated and lively on a Sunday afternoon, the government sector was deader than a graveyard, except for the cars racing through the area.

Los Angeles City Hall (above) was the exterior for the Daily Planet in the old Adventures of Superman series from the 1950s. The O.J. Simpson criminal trial occurred in the building to the left in 1994-95.

The Modernist building where the Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning is housed in the government sector has a plaza attached to it, working hard at being as empty as the day it first opened, no doubt. The ironic symbolism seems appropriate.

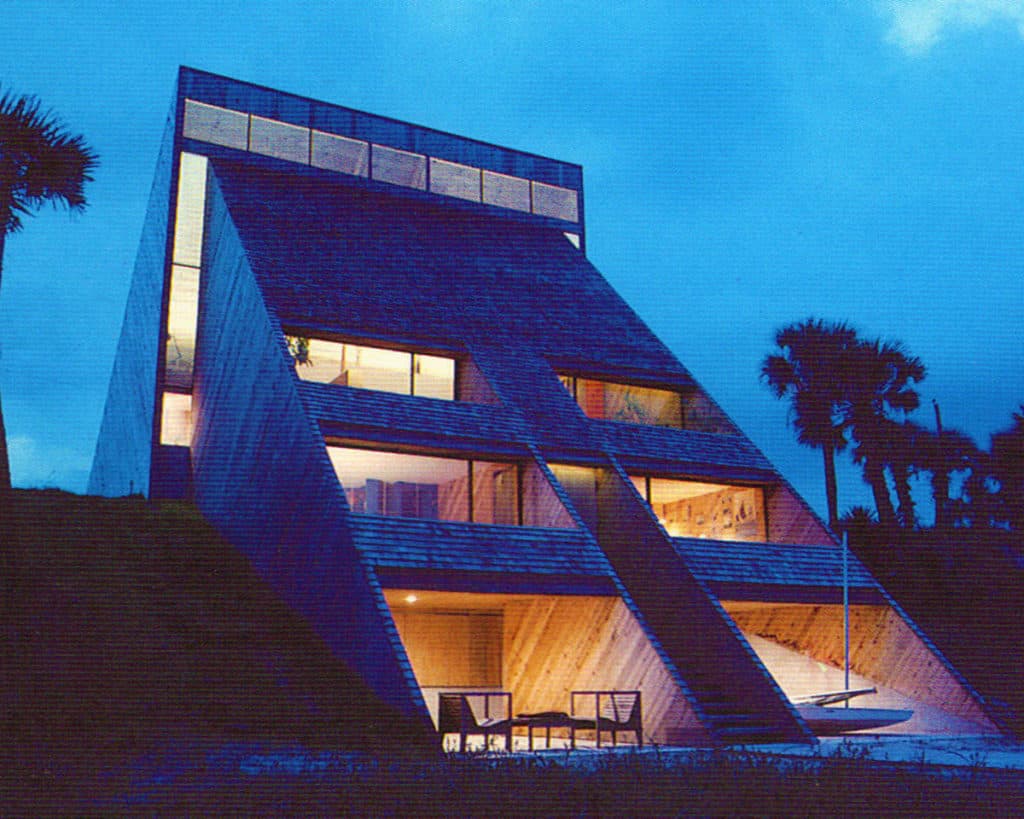

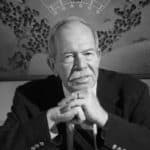

William Morgan was an American Modernist architect based in Jacksonville, Florida, who passed away earlier this year (December 14, 1930 – January 18, 2016). Three of his designs are included on the Florida Association of the American Institute of Architects list of Florida’s Top 100 Buildings including The Williamson House in Ponte Vedra Beach, Morgan’s Residence in Atlantic Beach, and Dickinson Hall at the University of Florida. Morgan grew up in Jacksonville and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University before serving in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War. After the war, he returned to Harvard to study architecture. He studied in Italy on a Fulbright Scholarship and then returned to Jacksonville to open his architecture practice in 1961 (Source: Wikipedia; Photograph: Florida Times-Union).

William Morgan was an American Modernist architect based in Jacksonville, Florida, who passed away earlier this year (December 14, 1930 – January 18, 2016). Three of his designs are included on the Florida Association of the American Institute of Architects list of Florida’s Top 100 Buildings including The Williamson House in Ponte Vedra Beach, Morgan’s Residence in Atlantic Beach, and Dickinson Hall at the University of Florida. Morgan grew up in Jacksonville and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University before serving in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War. After the war, he returned to Harvard to study architecture. He studied in Italy on a Fulbright Scholarship and then returned to Jacksonville to open his architecture practice in 1961 (Source: Wikipedia; Photograph: Florida Times-Union).